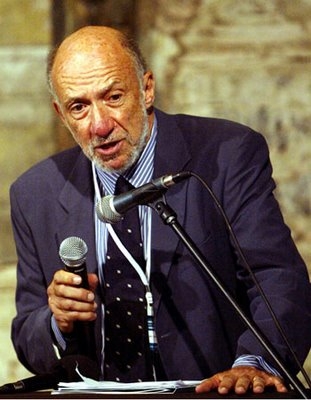

Professor Richard Falk is the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. He is world-renowned as an authority on international law and has authored and co-authored 20 books.

Recently, Professor Falk has focused much of his attention on the Israeli massacres in Gaza, alleging that Israel’s actions are constitutive of both violations of the laws of war and indicative of crimes against humanity.

Corey Balsam of the Alternative Information Centre interviewed him from his home in Santa Barbara, California.

Corey Balsam: Can you begin by explaining the reasons why you believe that Israel is guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity?

Richard Falk: Well that’s a big question of course. I think that the attack on Gaza initiated on December 27 of last year was a violation of a fundamental norm of the UN Charter, which prohibits non-defensive uses of force. At the Nuremburg trials after World War II, that was treated as a crime against the peace, which was viewed as the most serious of all international crimes.

Following from the attack itself, which was not a justifiable use of force, is the whole question of whether the use of modern weapons in a setting where the civilian population is exposed to the ravages of war can ever be reconciled with the international law of war. I believe it cannot be. That conclusion is somewhat controversial, it hasn’t been formally tested in an international tribunal, but I think the inability to prevent civilian casualties has clearly been established by the results of the attacks on Gaza.

Beyond the actual physical death and injury endured by Palestinians, including many women and children, is the wider reality that being trapped in a war zone of that sort almost certainly imposes severe and maybe incurable mental damage to the entire population. So it is a matter of waging war against a whole civilian population. That is, it seems to me, the essence of the most serious violation of the law of war. And it was aggravated in this situation because the civilians in Gaza were not even given the option to become refugees. They were locked in the war zone and therefore deliberately trapped in this combat area, which was so densely populated and being attacked from the sea and the air and by land.

Finally is the issue of the tactics and weapons that were used. There is a lot of eye-witness evidence that prohibited targets were struck, including several UN buildings; that civilians were deliberately targeted in an act of vengeance, apparently; and that legally dubious weapons were used in contexts where civilians were exposed to them, such as phosphorous bombs and a weapon called DIME, which involves a very intense explosive power that makes surgical and medical treatment impossible. So there’s a whole bunch of issues that together create quite an inventory of violations of the law of war as well as violations of the UN Charter.

CB: Considering geopolitical realities today, do you think there’s a chance that Israeli leaders will be brought to justice in any way, shape or form?

RF: I am skeptical at this point as to whether the intergovernmental framework of world politics has the capacity to impose legal responsibility on Israel or on its civilian and political leaders. And I don’t think the UN is likely to do anything significant although they have called for investigations of these allegations of war crimes and will give, I think, some further documentation to those allegations. But I am not very optimistic about implementing those reports by taking steps to impose accountability.

There are two areas where there is some prospect of a development that would move in this direction. One is indicated by the national court system in Spain that has encouraged the prosecution of 13 leading Israeli political and military officials. That at least establishes a legal claim by a governmental institution giving added credibility to the allegations. It’s doubtful whether it can be operationalized in terms of real prosecution, but it probably will prevent prominent Israelis at any rate from visiting Spain, and it will inhibit their travel plans.

The other possibility that I think is quite likely to take some form is the organization by civil society of citizen tribunals that will investigate these allegations and reach a judgment that can’t be enforced in a typical way but has a considerable symbolic weight. This will be influential for activists around the world who are already pursuing efforts to impose boycotts, encourage divestment from companies doing business in Israel and encouraging their governments to consider sanctions.

So I think one shouldn’t overlook the civil society impact of this dimension of concern about the criminality of what Israel did in its attacks on Gaza, and that that criminality has contributed to the mobilization of people around the world in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle. One needs to remember that that is eventually what turned the tide in South Africa and led to the victory of the anti-apartheid movement. It wasn’t a victory that was one by force of arms. It was a victory in what I call the second war, the legitimacy war, which eventually isolated South Africa in such a way that it internally transformed its constitutional and political system in a way that met the demands of international society.

CB: As you may be aware, a couple weeks ago over 40 cities in the world took part in the series of events called Israeli Apartheid Week. What’s your sense of the use of the term “apartheid” to depict what is going on in Israel/Palestine? Would you say that Israel is also guilty of the international crime of apartheid?

RF: Well I think that first of all, that event involving 40 cities is itself an illustration of the degree to which the Palestinians are winning the legitimacy war. That would not have happened a year ago much less five years ago. So symbolically, again, this is a very important development, independent of how literally that analogy should be pursued. I think that there is some mobilizing effect of using that analogy but there’s also some alienating effects, so it’s very hard to know whether that’s a tactically useful language to use. Each situation has its originality.

There are certainly resemblances that South African victims of apartheid have noted and there are dissimilarities. This is a military occupation that has its own characteristics that shouldn’t be overlooked such as the imposition of the settlements on the West Bank or the continuing blockade of Gaza. So I think that it is not inappropriate to use the analogy between the situation confronting the Palestinians and the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. But I find it less useful than to focus directly on the realities of the occupation as it affects the daily lives of the Palestinian people.

CB: As you were mentioning, the settlements have become a major problem. There are now about a half million settlers living in the occupied West Bank, not to mention the recently unveiled plans to double that number. Meanwhile, the international community remains steadfast on pushing for a two-state solution despite the seemingly irreversible physical realities on the ground. Given this, in which direction do you suppose supporters of a just solution should proceed at this point?

It’s a difficult question because both obvious paths of solution, two-state or one-state, seem very difficult to understand in regards to how one proceeds from the present reality to that solution. There’s no doubt that the further expansion of the settlements, if it actually takes place, represents the death of the two-state solution.

Even without the expansion, it seems very difficult to implement a two-state solution without dismantling a substantial portion of the existing settlements. At the same time, many people feel that no Israeli leadership would have the political will or capacity to implement such an approach, even if it was itself desirous of moving in that direction. But to expand the settlements, especially so massively, not only exhibits defiance of the international will on such a question, but it also is a repudiation of the Quartet peace process that had rested in part on a settlement freeze, which Israel consistently has ignored.

So I think if this expansion is not opposed effectively by the United States and by the Quartet, it represents the end of the Quartet peace process. This would introduce a new phase in the diplomatic approach to some sort of solution and would bring the one-state alternative into sharper focus. But there, one would have to think about whether there is a way to achieve a one-state solution that doesn’t involve the abandonment of Zionism by the Israeli leadership, because that would seem again to be beyond the realm of feasible politics. No foreseeable Israeli leadership would consent to renouncing Zionism as the basis of their governing process. If any leader were to do so, it is unlikely that he or she could survive politically and possibly even physically.

CB: Since being appointed UN Special Rapporteur you’ve been refused entry into Israel. Will you try again with the new government once it is formed?

RF: I will certainly explore the possibility. I would like to be able to carry out my role in a responsible way, which would involve visiting the West Bank and Gaza and meeting with people and their leaders there. I’m not very optimistic that a change of government in Israel will result in a change in policy toward my admissibility, but I will certainly do my best to carry out this job as well as I can.

Corey Balsam is a reporter with the Alternative Information Centre.

This interview was orginally published by the Alternative Information Centre and is reproducted with permission.