‘Deregulation for Wall Street crooks’ is one chapter of a manuscript entitled, Wall Street Thieves: the Crisis of Capitalism and the 99% Movement for a Just and Better World. I wrote the first draft of this book from Havana where I live half the year with my Cuban wife and family. Over the three months from November to January as I was writing the original draft, the rapid spread of the 99 per cent movement in the US and elsewhere was unfolding.

I had the opportunity to participate in the beginning of Occupy Vancouver, Canada assemblies in October, 2011 before returning to Cuba. That experience, from the perspective of 40 years of citizen activism, gave me a feeling of intense excitement and hope for a better world, a feeling I had not felt for decades.

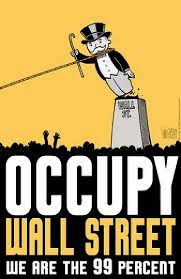

Back in Cuba as I began writing about the financial crisis, news kept pouring in about the occupy movement which began by targeting Wall Street through occupying nearby Zucotti Park in New York City and then promptly re-naming it Liberty Plaza. And the people said, “we are the 99%,” we are those left out by Wall Street. This bold action caught my imagination and the imagination of many people all over the US, in Canada and well beyond. It seemed a new era was being born as the movement spread like wildfire. Suddenly talking about capitalism as a huge problem to be overcome made sense to a lot of people.

*

Wall Street crooks: A brief history of financial deregulation

After the series of financial crises and stock market crashes since serious deregulation began in the 1980s, crises clearly caused by the same deregulation and financialization, what did the captains of finance devise? More deregulation!

In 1999, the passage in Congress of the Financial Services Modernization Act (FSMA) under the Clinton administration repealed the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. As previously discussed the Glass-Steagall Act had been passed as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal to keep commercial banking separated from investment banking in the wake of the financial manipulation and insider trading following the 1929 stock market crash.

Under the FSMA, investment banks, commercial banks, brokerage firms, and insurance companies can now freely invest in each other’s businesses, and fully integrate their financial operations. The act also allows the financial capitalists to set interest rates, thus completely by-passing the Federal Reserve Board. Moreover, the FSMA empowers Wall Street financiers to buy up State level banks all over the US and to acquire and take over banking institutions across the world. The FSMA, in conjunction with the General Agreement on Trade in Services 2000 (GATS 2000), opened the way for the ultimate domination of Wall Street finance capital.

The role of GATS and the WTO

GATS 2000 under the World Trade Organization (WTO), was created by a powerful coalition of corporate service providers, including financial services. The WTO is another elite body established in 1995 to regulate global trade and investment according to the principles of “freedom of trade and investment.” In the words of its founding director Renato Ruggierio in the year 2000, the role of the WTO is to coordinate global policy from the top: “If we want real coherence in global policymaking and a comprehensive international agenda, then coordination has to come from the top.”

What does that mean? The coalition that set up GATS 2000 included US, European and Japanese financial and corporate interests. The U.S. group included Wall Street financial giants, Citigroup, Bank of America, J.P. Morgan Chase, and Goldman Sachs. GATS 2000 is a far-reaching protocol to compel governments to provide unlimited market access to foreign service providers without regard for environmental or social impacts of the service activities. The FSMA of 1999 was a pace setter for GATS 2000. National governments, already under the yoke of external finance capital due to debt, would have no recourse to prevent Wall Street financiers entering their countries and grabbing up national banks and financial institutions.

Several Wall Street financial players engineered the passage of the FSMA. Here are three key examples. Lawrence Summers (already mentioned) was Clinton’s Treasury Secretary in 1999. Summers played a key role in lobbying congress for the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act.

Robert E. Rubin, who had been Clinton’s Treasury Secretary before Summers and helped set the stage for the passage of the FSMA while Treasury Secretary, helped broker the final deal on the Act between the House, the Senate and the Clinton Administration after he was replaced by Summers in Treasury. A few days after the deal was made Rubin accepted a position as a top senior consultant with Citigroup one of the main beneficiaries of the deal. Rubin was paid an annual base salary of $ 1 million, plus deferred bonuses (to avoid or reduce taxes) for 2000 and 2001 of $14 million, and stock options for 1.5 million shares of Citigroup stock. He made $126 million in cash and stock over the next ten years.

Neal Wolin supervised a team of Treasury lawyers responsible for reviewing the legislation repealing Glass-Steagall during the Clinton administration. All are key players in the Obama administration: Wolin as Deputy Secretary of the Treasury, Summers as Director of the National Economic Council until late 2010 (i.e., Obama’s chief economic advisor) and Rubin, while holding no formal position in the Obama administration, remains a key economic advisor.

In the U.S., de-industrialization accelerated in the following decade after the year 2000. Growth in real GDP slowed even more so than in the 1990s and 80s. Many factories closed “laying off” workers indefinitely (or we might say permanently). The service industry did supply some jobs, but nearly all these were part-time “McJobs” at McDonalds and other low priced outlets of mass consumption. The economy was not only stagnating, it was de-industrializing. Yet consumption continued except for a short break after 9/11 in 2001.

Stagnation only provides a partial explanation for what was happening. Yes, the US was de-industrializing and capital was financializing. Financialization, referring to the growth of the so-called FIRE industry (finance, insurance and real estate), was accelerating. The share of profits of financial corporations rose from 17 per cent of total domestic corporate profits in 1960 to 44% by 2002. As the financial industry grew, they inventing a dizzying array of new tools to add to short selling, such as credit default swaps, consolidated debt obligations, various kinds of futures trading options, and mortgage backed securities. Very often these new arrangements were transacted through hedge funds.

Hedge funds: Almost completely unregulated

Hedge funds are private investment funds. They manage the pooled funds of wealthy and not so wealthy investors. They are often linked to major financial institutions such as investment banks. With these large pools of financial capital, hedge fund managers undertake highly leveraged (i.e., largely debt financed) speculative transactions. Hedge funds house the range of derivatives, options, futures, etc. Yet hedge funds do an estimated 50 per cent of the daily trading of stock in the US. Because the pools of funds are so large, quick profits can be realized when the market goes up or down. After the repeal of Glass-Steagall hedge funds were almost totally unregulated. Hedge funds are also linked to the secretive offshore banking system.

The mania for faster and faster turnovers grew apace. Hedge fund managers with fortunes of $100 million or more were merely bit players in a much larger game. The concentration of wealth at the top is very tight. The ten largest US financial conglomerates, centered in insurance and investment banking, held more than 60 per cent of all U.S. financial assets, compared to only 10 per cent in 1990. JP Morgan Chase alone held 10 per cent of all bank deposits in the US by 2008, as did Bank of America and Wells Fargo. These same three banks along with Citigroup now issue almost half of all mortgages and 67 per cent of all credit cards. This represents a very tight oligopoly indeed; so tight, it could be legitimately called a monopoly.

The financialization of the ruling class

The financialization of the U.S. capitalist ruling class is reflected in the following statistics. In 1982, oil and gas was the primary source of wealth for 22.8 per cent of the Forbes 400 richest Americans. Manufacturing was 15.3 per cent, while finance was only 9 per cent. By 2007, finance was the primary source of wealth for 27.3 per cent of the Forbes 400, while manufacturing only represented 9.5 per cent. Oil and gas was now at only about 9 per cent. The technological revolution of the last thirty years, so much touted in the capitalist press, peaked in 2002 at about 18 per cent, but fell by 2007 to just over 9 per cent.

Executive compensation of the financial sector also increased dramatically. In 1988, the top ten in executive compensation did not include any from the financial sector. By 2000 finance accounted for the top two. By 2007 four of the top five were from finance. Clearly, over the past thirty years a significant shift has occurred in the structure of the ruling class in the U.S.

Financialization has also become a more important element in non-financial corporations. For example in 2005, financial operations of Deere & Company, manufacturers of farm equipment, produced 25 per cent of its earnings. Also, in 2005 retailer Target Corporation got about 15 per cent of its earnings from finance. General Motors’ financing operations in 2004 earned $2.9 billion, while it actually lost money on cars.

The lack of regulation over the entire financial industry especially over requirements to back up speculative transactions with reserve funds meant highly leveraged trades became commonplace. Debt grew greater and greater. The debt of the financial sector represented 10 per cent of total U.S. debt in 1975. By 2005, the financial sector’s share of total US debt was very close to 30 per cent.

While financialization and de-industrialization both grew in the U.S., consumers just kept on buying more stuff through increased use of credit cards under the influence of an increasingly hard-selling advertising industry, the big sales pitch.

Yet, who was making the consumer goods, if US industry was de-industrializing? Well, as the world now knows, China, especially in the first decade of the 21st century, has become the new ‘workshop of the world’. German and Japanese high quality machines and technology supplied Chinese factories, suddenly giving them the ability and capacity to produce high quality consumer goods for the US working and middle classes at the lowest possible prices (as well as for many other Western countries). Although real wages have fallen in the US, as we have seen, the much cheaper Chinese made goods allowed Americans to keep consuming through cheap mass consumption outlets such as Walmart.

Michael Carr is a retired instructor at Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia who has been an activist for social justice for over 40 years.