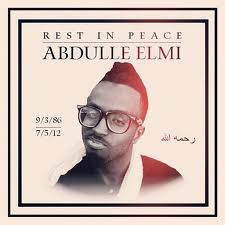

My friend Abdulle Elmi was killed in July. He was a victim in one of the shootings that took place in Toronto this summer. We were friends, but I never got the chance to meet Abdulle.

We knew each other exclusively through the Internet. We had a digital friendship without a single in-person interaction to back it up. I think about that now after his death. It seems surreal.

Abdulle was one of many friends I made online when I made the active decision to begin the quest for community. We connected because he wanted to join a conversation that was happening on social media. A race-baiting scandal was taking place during student elections, and some students at U of T and I were talking about it on Facebook.

Up until that point, I didn’t even know that Abdulle and I went to the same school — let alone that we studied in the same classrooms and read the same books. But I discovered that we had those things in common and a lot more. His domain name was Mick Swagger, and that’s how I knew him. Although we only chatted a handful of times over the past year, every conversation was substantive, meaningful and kind.

Abdulle was a fierce and eloquent advocate for political issues that often go unnoticed. He had a passion for equity, social justice issues and anti-racism praxis. He also had a huge love of music. Hip hop and rap, soca beats, bossa nova, music from all around the world. Like so many of us, Abdulle used music as an escape and a release.

But he also used music to actively inspire the people around him. An MC, he was known as Black Wizard, or simply Wizard. His life experiences often bled into his verse. He had an abiding commitment to community and to building up young communities of colour. We both did this work in Toronto.

But because I knew him as Mick Swagger, not Abdulle Elmi, it took me a long time to realize he was the shooting-victim listed in the news reports. And because of our Internet-only friendship, I made that connection on Facebook. First, I noticed that an unusual number of people had posted on Mick Swagger’s Facebook wall. Then I went to his page and learned that Mick Swagger was Abdulle Elmi. It was like being punched in the gut.

I don’t have much experience with death. My family is relatively young — and those that did pass away in my family did so before I was old enough to grasp death’s implications. But to face death so plainly, along with the rest of Abdulle’s online community, and to still feel so alone — it was not fun.

When I look at his Facebook wall now I see a patchwork memorial erected by loved ones: friends and family from Minnesota, Toronto, Japan — all over. It’s really incredible how many people one person was able to touch in a positive way.

One of the questions Abdulle’s death has left me with is about the vibrancy of my Internet community and why I have chosen to turn to the Internet for community instead of connecting to the live people around me. It’s harder than you think finding your ‘community.’ By this I mean that I began to look for the people around me who understood me. The young people who understood where I came from and what I was about — in spite of whatever distance separated us. Sometimes these folks, like Abdulle, turn out to have lived around the corner from me the whole time.

I believe people shouldn’t find out about death through the Internet. Although it is becoming more and more common to do so, finding out in that way means you are alone with death. For me, a message borne by a living, breathing vessel is always easier to handle. The pain of death should be tempered by a human touch. Even in death, there should be love.

No such luck this time. Actually, it was the opposite. Earlier this summer, I was disturbed by and reported on the Eaton Centre tragedy. Since then we have seen several other incidents of gun violence. The majority of the casualties this summer? Young people of colour. And one of the victims was a friend.

Abdulle was a part of a summer of violence I’ll never forget. The violent deaths of young black men are often perceived in statistical form. Like a social ill or a problem to be solved in theory. But it is worth remembering that behind every dehumanizing political statistic there’s a person.

Abdulle made the personal political.

Muna Mire is rabble’s podcast network intern and also a student in her final year at the University of Toronto where she is currently completing an Honours B.A. in English, Political Science and Sociology.