When it came to television my parents were not early adopters, so the 1950s, when I grew up, were still radio days for me.

I used to get glimpses of Howdy Doody, Bugs Bunny and the “indian head” test pattern at my grandparents and at friends.

At home it was all radio, all the time, and radio meant one thing: the CBC.

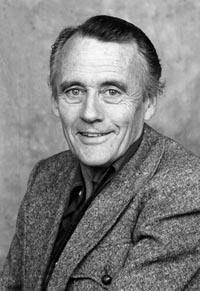

That’s how I got to know the great CBC legend, Max Ferguson, who died in Cobourg, Ontario, on March 7.

I didn’t know him as Max then. I only knew “Ole Rawhide”, his one-air alter-ego.

My parents were big fans, both for the political satire and for the folk music from around the world.

Ferguson was just about the only disc spinner — back in those days of Joe McCarthy, the black list, and (in Duplessis’ Quebec) the padlock law — who would regularly play otherwise shunned performers such as Peter Seeger and The Weavers.

The folk group The Weavers, of which Seeger was a member, had some big hits in the late forties and early fifties, but then came under FBI surveillance for supposed “Communist” connections, and disappeared completely from the airwaves and mainstream record company catalogues around 1953.

U.S. broadcasters were so craven they wouldn’t put Seeger on the air, again, until the late 1960s, long after Joe McCarthy had died and the House Un-American Activities Committee had disbanded.

When called before that Committee, by the way, and asked if he was a Communist, Seeger refused to answer, not on the grounds of self-incrimination — the Fifth Amendment — but on the grounds of free speech, the First Amendment. He won that landmark case in 1961.

I don’t know how much of a radical Max Ferguson was back in the 1950s, or later on, for that matter. Whatever his political views, he regularly played Seeger, along with other political outcasts such as Paul Robeson (he of that unparalleled, deep voice) — and damn the torpedoes.

One of Ferguson’s favourite artists, he said in later years, was folksinger (and actor) Ed McCurdy, who was American by birth, but spent much of his professional life in Canada.

McCurdy’s best known song was “Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream”. Even if you don’t know his version, you’ve probably heard it “covered” (as they say in the music business) by Simon and Garfunkel, perhaps, or Arlo Guthrie:

“Last night I had the strangest dream/ I ever had before / I dreamed the world had all agreed / To put an end to war.”

On his “Rawhide” show Max would also sprinkle in African guitars, Russian choirs and Yiddish lullabies.

He was into “world music” before that odd phrase existed.

(Whenever I hear the phrase world music I think of what blues shouter Big Bill Broonzy said about folk music: “All music has gotta to be folk music because I never heard a horse sing!”)

The Rawhide show was not just about music, it was also a vehicle for Ferguson’s sketch comedy. Again, Ferguson was a pioneer, doing on-air satire long before SCTV or Saturday Night Live.

He did all the voices, amazingly, and had a cast of characters that included the velvet-voiced broadcaster Marvin Mellowbell, and a rough-hewn, sarcastic character whose name I never learned, but who was my favourite. Years later, I heard Max explain that he based this guy’s accent and speech patterns on the Ottawa Valley twang.

I may have been a bit young to catch the political satire in the 1950’s Rawhide Show, which was based in Halifax. But when Max moved to Toronto, teamed up with Allen McPhee, and started doing send-ups of politicians, from Diefenbaker to Pearson to Trudeau, I was quite old enough to get the jokes. I frequently listened while commuting to or from work.

Max was on the air for a long time, it seemed, in various formats and at various times, doing both topical sketches and interviews, almost always with the curmudgeonly McPhee as his foil.

I think he was even, for a while, on television, an obligatory rite of passage (or passage in hell?) for so many CBC radio folk, from Peter Gzowski to Ralph Benmergui to Viki Gabereau.

Then, in 1977, I went to work for CBC radio myself and met the man behind all those voices, in person.

I worked at the old Morningside show in Toronto, when it was hosted by comedian Don Harron and produced by the late Krista Maeots.

Ferguson seemed to be between engagements at that time, as far as I could tell. Word about was that he was planning to re-settle in Cape Breton — and he did seem to feel a calling for the simple life.

He was, from time-to-time, a guest host on Morningside, back then — a task that he carried out with grace and aplomb, though the show made no room for his satiric sketches in a variety of voices.

The desk next to mine, in those days before quasi-enclosed cubicles, was occupied by a young, charming and recently widowed Pauline Janitch, and Max took a great interest in her.

One is not supposed to eavesdrop, but in close quarters it was hard to avoid overhearing what folks were saying.

I still recall Max talking as discretely as he could to Pauline about a proposed date — or so it seemed to me. He was inviting her to go skating, and seemed almost apologetic about the plan. It won’t be serious skating, he said.

The next thing I knew, my wife and I were running into the two of them, happily together, picking up food at our neighbourhood Dominion Store.

I left Morningside not long after that, moved back to Montreal, then to Ottawa, then back again to Montreal — knocking around a fair bit, working in both English and French, in both radio and television.

Our family of three grew to a family of five, and life got pretty busy.

Pauline and I lost track of each other — until, through Facebook, she found me again, a couple of years ago.

I learned that Max and Pauline had been living east of Toronto, in Cobourg, a few blocks from Lake Ontario, that Pauline had commuted to Toronto for a number of years, where she kept working at CBC, until she finally retired, and that she and Max have a son, Tony, an aspiring journalist.

Pauline still remembered a concert she, my wife Marty, and I attended together at Massey Hall, in Toronto, back in 1977 or ’78. Performing that night was the late, great jazz violinist Stéphane Grapelli, one of my enduring musical heroes.

I told Pauline how my whole family had been big Max Ferguson fans, going back to the days of Rawhide, and that touched them both, she replied.

She encouraged us to drop by their place in Cobourg on our way to visit friends and family in Kingston or Toronto.

That never happened, but we did stay in touch through the magic of the Internet.

I was a bit surprised to read, after Max’s death, that the two of them had been together for 35 years. It seems like yesterday that a shy and reserved Max was courting Pauline, in the CBC’s ramshackle Toronto quarters, housed in an old girls’ school on Jarvis Street.

When that other legendary CBC broadcaster Peter Gzowski died about fifteen years ago, there was a fairly huge brouhaha in the media. The Ottawa Citizen put the news in a banner headline on the front page, and the CBC itself talked almost interminably about Gzowski for more than a week afterward.

Gzowski died young, while still, despite his failing health, an active figure.

Max had left the scene a while ago and died in his ninetieth year.

But Max was as much a giant of Canadian broadcasting as Gzowski — or as any of the other legendary figures from René Levesque to Barbara Frum.

It wasn’t always wine and roses for him at the CBC either. Even with his more than half century on the air, and his many honours and awards, Max lived through some bruising times, professionally. (Of course, who hasn’t? Certainly very few who ever worked at CBC.)

Before moving into Cobourg itself, Pauline reported to me that she and Max lived in the country, for a while, where he “raised bees, killed bees (an unexpected early April frost), grew vegetables and cut wood for our stove. (every log was blessed with the name of a former CBC executive) . . .”

No doubt Ole Rawhide will turn up every once in a while on one of those CBC radio shows where they plumb the archives.

When you listen to “world music” today, or laugh at satirical sketch comedy, think of Max Ferguson, who — without ego or pretense, and without bells and whistles any fancier than CBC sound effects could provide — was a true broadcasting pioneer.