In the venerable Canadian TV show Trailer Park Boys, Ricky points out the prevalence of marijuana in Canadian culture: “Everybody does [marijuana], all right? Carpenters, electricians, dishwashers, floor cleaners, lawyers, doctors, fucking politicians, CBC employees, principals, people who paint the lines on the fucking roads, get stoned, it’ll be fun, get to work!” It’s a part of Canadian identity that separates us from our southern neighbours and yet hypocritically remains prohibited.

Roger Evan Larry’s new documentary Citizen Marc is at once a portrait of a singular figure of marijuana activism, Marc Emery, and a study of Canadianness more generally.

Using archival footage, legal and media documents, animation and interviews with Emery himself as well as politicians, academics, journalists and activists, the film presents contradictions, but does not resolve them, instead taking the more productive position that identifying injustice and enacting social change requires embracing ambiguities and complexities.

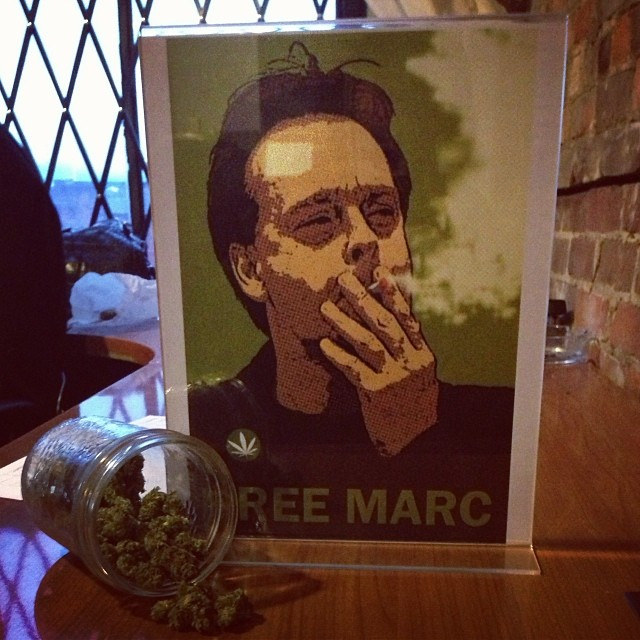

The film opens with Emery giving a press conference about his impending extradition to the U.S. for selling marijuana seeds, an offense that would garner a fine in Canada, but a substantial prison sentence in the U.S. He is surrounded by supporters holding up signs — “Free Marc Emery” — and his rhetoric follows the mould of civil rights activists and political prisoners throughout history.

Emery speaks of the Canadian government abandoning their citizens abroad and refers not specifically to the U.S. but a “foreign country,” trucking in vague signifiers to stir up anger and support. The form is familiar as civil disobedience and the content of his speech, taken in isolation, could refer to anything.

Supplying this content, the film cuts to an image of Emery smoking an enormous joint and the Beastie Boys’ “Fight for Your Right (To Party!)” on the soundtrack, thus deflating the somewhat absurd comparison of fighting Canadian injustice regarding marijuana laws to colonialism and racism.

The film uses juxtaposition in this way throughout to add humour and insight, ensuring that we neither dismiss Emery’s overblown rhetoric nor lose sight of the importance of his struggle.

Emery compares himself to Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Mandela — arguing that all civil disobedience is equivalent in combating injustice — but the comparison that the film draws is to the iconic character Charles Foster Kane.

Like the famous newspaper baron from Citizen Kane, “Citizen” Marc embodies the tensions of his nation and historical situation, in both his immense ego and his substantial achievements. He is a champion of fighting injustice and allowing individuals to flourish unfettered by government or other restrictions; yet he allies with liberals as well as libertarians.

His philosophical hero is Ayn Rand and sees himself in Howard Roark, her version of the ideal man — a freedom-fighter, powerful and superior. He compares pot-smokers to Jews as “chosen people” facing discrimination, conveniently eliding the fact that pot-smoking is a choice in a way that ethnicity cannot be.

Moreover, Emery recounts the origin story of his personal mythology as an actual, pseudo-religious prophecy: a woman hit her head outside his bookshop, went into a coma and told him when she awoke that she dreamed of three symbols that relate to his greatness — the dollar sign, a map of the brain and a marijuana leaf.

This prophecy provides him with both the external validation for his inherent messianic complex and a sense of destiny for his righteous persecution.

He sees himself as a hero of justice against the evil state, in the immutable morality of a classic comic book — indeed, the film makes use of this self-identification by humourously depicting Emery’s battles in animation when his rhetoric gets excessively self-aggrandizing.

The film explores each of the prophesized symbols in turn to create a portrait of Emery and his contexts.

Emery’s relationship to the dollar sign was clear from an early age; he dropped out of high school because his various entrepreneurial endeavours were successful, from selling time with his toys to childhood friends to opening the bookstore that eventually became the front for his seed business.

Yet he professes not to love money for its own sake, but rather for philosophical purposes — to invest in the fight against injustice. His belief in the strength of his own brain is evident in his superior attitudes towards his fellow citizens.

For Emery, Canadians are complacent, dependent on the state and require a leader — himself, naturally –to instigate them to action and the fulfillment of their individual potential.

As for the pot leaf, the “Prince of Pot” actually didn’t smoke until adulthood. Initially, the content of the struggle did not matter; pot was a way to make money and invest in his larger anti-state revolution. However, Emery cleverly taps into people’s emotional attachment to marijuana and the hypocrisy of its criminalization to attract supporters from across the political spectrum.

Citizen Marc allows viewers to come to their own conclusions about this complex figure who appears to be simultaneously a product of his own ego, the media and various cultural, national and legal discourses.

Is he a narcissistic megalomaniac striving for recognition and fame? Is he a selfless activist willing to go to prison for his beliefs? To be sure, he can occupy multiple positions and the film obviously admires much about him.

Mass incarceration as a result of the War on Drugs is a serious issue, one that circulates in culture in particular ways — see, for example, Kanye West’s “New Slaves” — but certainly requires more in terms of active critique and pragmatic change.

Furthermore, if we believe that the nation-state is a valuable entity, then Emery’s struggle throws into stark relief problems of Canadian sovereignty — the same government that extradited Emery prioritizes Canada’s claims to the Arctic Ocean.

What do we want our country to be and what will we do make that happen?

Citizen Marc is an engaging, funny, thoughtful documentary if you are interested in these questions.

Shama is a PhD student at the University of Alberta whose research is on the politics of visibility in modernist literature and film.

Photo: flickr/Cannabis Culture