May 1 International Workers’ Day, commemoration and protest celebrated around the world, may be behind this year, but the legacy and lessons of the day stay with us throughout the year, particularly as we head into our federal election.

The Canadian legacy of May Day is not as well known. So, that’s one of the reasons that the Graphic History Collective decided to create May Day: A Graphic History. Ella Bedard, rabble’s labour beat reporter, asked the authors of the comic about the significance and contemporary relevance of the workers holiday in Canada.

(Psst! The Graphic History Collective will be tabling at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival this coming Saturday May 9. Check it out!)

I think the central May Day event that sticks out in many peoples’ minds is the Haymarket massacre. Can you point to an instance or two from Canada’s May Day history?

There are so many inspiring moments from May Day’s past in Canada, and we try to cover a lot of these in the comic book. We are quite partial to the early May Day protests in Toronto and Montréal, when workers took up the call to commemorate the Haymarket Massacre and to use May 1 — International Workers’ Day — to strike to advance workers’ rights.

In Montréal, where the first recorded May Day observations happened in 1906, an estimated 10,000 people (which, of course, included women’s groups, although that is often forgotten) gathered, giving speeches in multiple languages on various topics. The police gathered too, and there was definitely some tensions that appeared at the event, including confrontations between the women marchers and police, as the police tried to prevent the women (and others) from unfurling and marching with their red banner.

Often, and unsurprisingly, when there is an economic recession or downturn the May Day marches have a larger turnout. Photographs from May Day marches in Vancouver during the 1930s, for instance, show long lines of marchers and huge crowds of people; however, the interesting moments are not only limited to big cities.

A little known but interesting gathering happened in 1931 in a small town in British Columbia, called Natal, near the B.C. border. A park was temporarily named “Karl Marx Park,” and people from both provinces gathered to hear noted union leader and organizer Harvey Murphy speak. Mixed in with these events were more traditional and seasonal celebrations of May Day, including dancing around the May Pole and having a feast together.

Two more recent events that are inspiring and worth noting are the massive May Day strikes in Québec in the early 1970s and, since 2006, the annual marches held by No One is Illegal in Toronto.

What is the significance of May Day today? Has its relevance changed, given the changing nature of work and of the labour movement?

The meaning of May Day is constantly negotiated by new generations of workers. Many people in Canada, though, still don’t realize that “May Day” is actually International Workers’ Day and is celebrated around the world. We created the May Day comic book to raise awareness about the importance of this holiday in Canada and to inspire people today to reclaim it and use it to advance workers’ rights.

The beginning of May has for thousands of years been celebrated as the arrival of spring, and many ceremonies and festivals were popular features of everyday life in many different cultures. So, in some ways, workers in the late 19th century borrowed that energy and crafted May Day as a day to celebrate the power of workers in response to the arrival of the brutalities of industrial capitalism.

Since then, new workers have shaped May Day into a day of protest that reflects the interests and priorities of the day. We see this in the Migrant Workers’ Rights rallies now popular in many big cities across North America. We see it in efforts from organizations like No One is Illegal to expand the focus of May Day struggles mean and who is represented by these struggles, drawing attention to what types of bodies are allowed to move freely and the ways work connects to place and land. They have an eight-point platform for their May Day rallies that includes Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination, migrant workers’ resistance to border imperialism, environmental justice, militant rank and file labour movements, and gender justice.

May Day is truly a day of the people and, as such, is defined by the workers who choose to organize and participate. May Day is an inheritance of sorts and, at the same time, something that we shape and make our own.

The struggle for the eight-hour work week is also central to May Day’s history. Can you say little bit about the historical significance of that movement? And do you see any contemporary parallels to it?

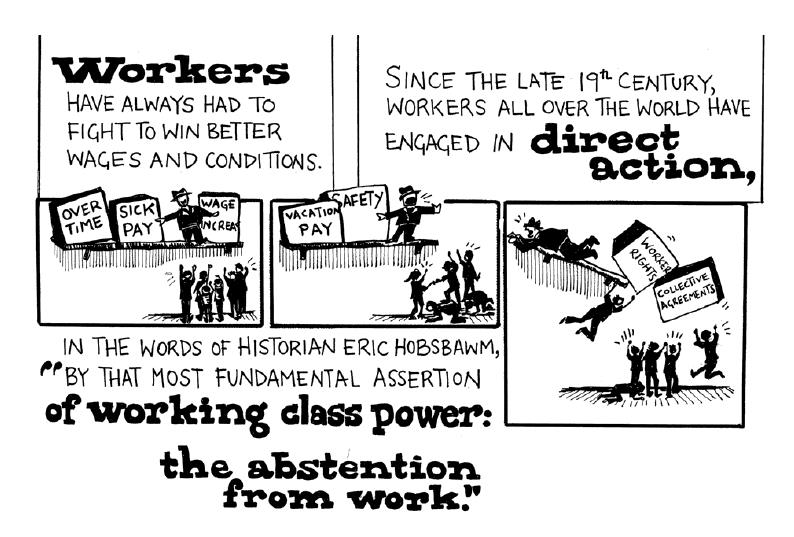

The fight for the nine-hour and then the eight-hour day, really, is at the heart of May Day. People sometimes forget that the Haymarket massacre was related to a big strike for the eight-hour day called for May 1, 1886 in Chicago, as we show in the comic book. This fight seemingly came out of nowhere (though there was a lot of organizing behind the scenes), and the great upheaval of 1886 — called that because of the many protests, strikes, and workers’ demonstrations that occurred throughout North America, including Canada — helped spur an organized labour movement that, though not perfect, helped workers achieve a variety of important gains, from the weekend and regular work breaks to the right to join a union.

Now, over 100 years later, in an age of austerity and crackdowns on workers’ rights that shares many similarities to the 1880s and 1890s, the labour movement is coming under attack. We need workers, again, to get organized and create new ways of fighting back and making the world a more just place for everyone.

Celebrating May Day, or International Workers’ Day, can be a way for people to connect to the history of the workers’ movement and participate in protests that point to the power of workers on a global scale. And celebrating May Day as International Workers’ Day is about making those connections between workers — and not just the workers who have “jobs”. Work isn’t just about careers. It’s also about unpaid domestic labour, child care, underpaid/precarious work, unseen work, the labour of being dis/abled, and so on.

The struggle for workers’ power, of course, is not just relegated to a one day protest/celebration on May 1. But May Day, and the beginning of spring generally, can be seized as an important time for workers to reflect on our efforts to change the world, both past and present, and to chart the necessary tactics and strategies to win moving forward.

Why did you feel the need to write/draw this comic? Why tell this story?

The history of working people is often seen as boring or unimportant. Instead, what we often learn about history in school and popular culture is the importance of politicians, monarchs, and capitalists. Workers are sidelined in these histories. We are inspired to use the popular medium of comics to share stories of workers in hopes that they can renew people’s hope for social change and encourage people, especially youth and young adults, to get organized.

Anything else I should know about May Day, the comic, or the Graphic History Collective?

Between the Lines Press is offering a special offer of FREE shipping and 40 per cent off bulk orders of the May Day comic book until May 30. So ask your school, union, or social group to make an order and help spread the word about May Day and Canadian labour history comics. You can also purchase individual copies directly from Between the Lines, including an E-book version.

Also, members of the Graphic History Collective will be tabling at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival this coming Saturday May 9 and will be giving away five free copies of the May Day comic book. So drop by and say hello.

As for our future projects, we are currently working on a new comics anthology that examines the lessons of Canada’s labour and working-class history for a popular audience called Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working-Class Struggle. The anthology will be published by Between the Lines Press in spring 2016 and is full of great comics projects by members of the GHC as well as a number of talented artists and writers, including Jo SiMalaya Alcampo, Althea Balmes, Christine Balmes, Nicole Marie Burton, Ethan Heitner, Orion Keresztesi, David Lester, Doug Nesbitt, Kara Sievewright, and Tania Willard, Secwepemc Nation. You can find our announcement on our website.

You can also connect with us online:

Website: www.graphichistorycollective.com

Facebook: GraphicHistoryCollective

Twitter: @GHC_Comics

Ella Bedard is rabble.ca‘s labour intern and an associate editor at GUTS Canadian Feminist Magazine. She has written about labour issues for Dominion.ca and the Halifax Media Co-op and is the co-producer of the radio documentary The Amelie: Canadian Refugee Policy and the Story of the 1987 Boat People.

Photo: Graphic History Collective