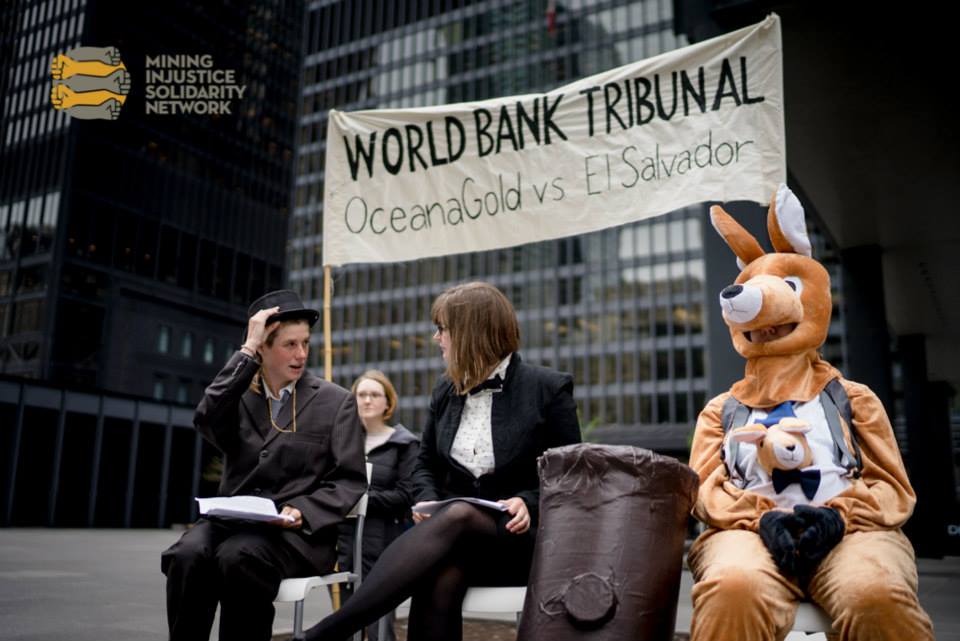

Friday morning, a delegation of anti-mining activists, along with one in a kangaroo costume, made a visit to the Toronto office of Industry Canada and the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development.

They were accompanied by a delegation from El Salvador, visiting as part of the Stop the Suits Tour, organized with MiningWatch Canada, SalvAide, the Mining Injustice Solidarity Network, the United Church of Canada and others. They were there to draw attention to a petition with over 175,000 signatures, asking mining company OceanaGold to drop its $301 million lawsuit against El Salvador.

The Canadian-Australian mining company wants El Salvador to pay for blocking the El Dorado gold mining project, and the protest aimed to draw attention to Canada’s support for the policies that enable such action.

Speaking at the 25One Community offices in Ottawa as part of the delegation, Deputy Attorney of the Environment for El Salvador’s Human Rights Prosecutor’s Office Yanira Cortez painted a stark picture of the country’s environmental conditions.

Whereas Guatemala has 40 per cent forest cover, El Salvador has only 13 per cent, two per cent of which is indigenous forest growth. According to Cortez, the country is entering into a period of severe water stress, with more than 90 per cent of surface waters contaminated.

With this crisis on the horizon, Salvadorans have been demanding a halt to all mining in the country. Over seven years, three successive Salvadoran governments have responded to these broad-based anti-mining movements by upholding a de facto moratorium on new metal mining projects.

Well before the moratorium was put in place, Canadian mining company Pacific Rim knew that it had failed to fulfill the requirements needed to obtain mining permits, but thought it could get its way through high-level lobbying. Then, in 2008, then-president Saca initiated the moratorium on new mining projects permits. That’s when the country found itself caught in a web of international corporate law and free trade agreements.

OceanaGold bought Pacific Rim in 2013 and has taken up the former company’s mantle, continuing to pursue the $301-million lawsuit against El Salvador.

To put that amount of money into context, $301 million amounts to 5 per cent of El Salvador’s total GDP. It is roughly equivalent to what the country budgets for three years of health, education, and security costs.

“For a country like El Salvador, a $301 million fine, there’s no choice of whether or not to keep the policy,” said CCPA Monitor’s Senior Editor Stuart Trew, who also spoke at the Ottawa event. “If an investor panel says you can either get rid of the policy and allow the mine, or pay $301 million, that’s extortion, that’s not a choice.”

What, exactly, do those kangaroos signify?

While the intricacies of international investment law can be hard to follow, the problem starts with the investor-state dispute settlement provisions (ISDS) included in most international trade and investment agreements.

Through these ISDS provisions, foreign investors have a right to seek damages if they feel that they are being denied fair treatment by their trading partners.

Pacific Rim was able to file a case against El Salvador with the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), claiming that the company has violated a nondiscrimination clause of the U.S.-Dominican Republic Central America Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA), which the Canadian mining company has tenuous claims under because it has some U.S. subsidiaries.

In its claim, the company also made reference to a Salvadoran investment law that permits foreign companies to take their disputes to ICSID. While the law has since been reformed to prevent other companies from using the ICSID in this way, the case is proceeding under this investment law because the ICSID ultimately ruled out the company’s attempt to get the tribunal to claim jurisdiction under DR-CAFTA.

Overriding national court systems, cases like this one are heard by narrowly focused international arbitration tribunals that do not take into account the collateral damage of business; what MiningWatch is calling the kangaroo courts of international corporate trade.

“These international tribunals do not consider human rights in their judgements, only the value of future lost profits,” Cortez explained. The legal counsel for the State of El Salvador tried to have Cortez testify before the tribunal. As a representative of the Departments of the Human Rights Ombudsman, she could have testified to the environmental impacts and human rights violations caused by mining, but their request was denied.

“They do not need to respect jurisprudence or precedent, they look only at what affects the laws will have on company,” Cortez explained. “But they don’t care what the company has done in the country.”

While Labour and Environmental activists have found plenty of reasons to oppose free trade agreements, says Trew, no one really anticipated that the investor-state dispute settlement provisions buried in agreements like NAFTA and the CAFTA-DR would be used, as they increasingly are, to get around unfavourable domestic policies.

Mining Watch reports that as of 2013, 169 investor-state suits are being heard at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, which oversees the tribunal processes for the CAFTA-DR agreement. That number is up from only 3 cases in 2000.

Roughly 35 per cent of those suits were brought by oil, gas, and mining firms and nearly 50 per cent of all 169 suits were against Latin American governments.

Canada is not immune

MiningWatch notes that the trend with NAFTA suits are similar. Over the last decade, the number of investor-state cases being filed between countries under the NAFTA agreement has double, and Canada is the target in roughly 70 per cent of those cases.

In an ongoing case, oil and gas company Lone Pine Resources filed a $250-million NAFTA lawsuit against Canada over Quebec’s moratorium on fracking for oil and gas underneath the St. Lawrence River.

Paralleling the Salvadoran case against OceanaGold, Quebec is being charged with discriminating against its trade partner for putting environmental and health concerns above corporate interests.

“If all the pending tribunal cases against Canada are won, that will cost us $2 billion, or about what we’d need to spend on a universal child-care program,” Trews explained. “And why is Canada sucking it up without fighting these? Because they have a vested interested in cases like OceanaGold vs. El Salvador,” he added.

A growing number of countries, including Australia, Indonesia, and South Africa, are starting to look critically at ISDS provisions, refusing to sign new trade agreements with these provisions, or else letting them expire. With widespread protests against the provisions in Europe, it remains to be seen whether investment-state provisions will be included in the new EU-North American agreement.

The Salvadorian delegation presenting this week is here to warn Canadian about the hidden risks that trade agreements pose to human and environmental rights, to say nothing of national sovereignty. But they are also here to offer solidarity to another resource rich country made vulnerable by fast and loose free trade agreement.

“We are here to bring a warning that the same thing that is happening to us, is happening to you,” warned Marcos Gálvez, President of the Association for the Development of El Salvador. “While we are here looking for your solidarity, we are also here to offer ours. This world has to change and another world is possible.”

Ella Bedard is rabble.ca’s labour intern and an associate editor at GUTS Canadian Feminist Magazine. She has written about labour issues for Dominion.ca and the Halifax Media Co-op and is the co-producer of the radio documentary The Amelie: Canadian Refugee Policy and the Story of the 1987 Boat People.