First, a word on the all-important question of tone: now is not the time to be snide or sanctimonious (is it ever?) If there’s one thing this election made clear, it’s that campaigning in general, and communications in particular, are hard. Really hard.

Even the Conservatives’ vaunted comms machine faltered (thankfully, it appears there’s such a thing as too much racism, even with a dead-cat strategy). And if you phone bank or knock on doors (as I did for most of the major third-party orgs) you’ll quickly find that if you talk to 100 people, you’ll hear 500 different rationales for choosing particular candidates and parties. The challenge of weaving something together that checks enough of the various boxes people add and discard and rearrange in their mental maps during an overly long election can’t be overstated.

I yearned during this election for a reasonable counter-strategy from all the folks who publicly lamented the NDP’s rightward drift. What I heard repeatedly was that the NDP should have scooped Trudeau on deficit spending, or not been clear whether they’d balance the budget at all. Not only would the media have skewered them for this, but that would have made the all-important conversations on doorsteps even more challenging. There’s a “Nixon in China” quality to Trudeau promising deficit spending that we can’t ignore.

And what I also didn’t hear was much credit for all the good progressive policies the NDP released (admittedly likely too late, and with too little credibility on achieving them after the “fully costed plan” was flubbed, and the $15/hour minimum wage and childcare plan had significant caveats). Money to get the North off diesel, interest-free student loans, opposing the TPP, National Housing Strategy, hard carbon targets, etc. Lefty commentators need to be careful not to unfairly reinforce the negative mainstream media portrayal of the NDP as untrustworthy by ignoring these promises that are more in-line with the party’s public identity.

The NDP took more things from the left-hand column than some accounts acknowledge. But they also undeniably took from the right-hand column (the small business tax cut and no new taxes on high-income brackets plus no deficit spending did paint them into a corner). More than that, Desmond Cole argues very convincingly that they took too much rhetoric from the “mushy middle,” and the laundry list of policies didn’t amount to an inspiring vision.

But — what else could they do, after decades of super effective anti-tax rhetoric, and when neither Jeremy Corbyn nor Bernie Sanders have yet had a chance to check their overt progressivism against the mainstream electorate?

What else could they do, too, when deficit spending hands power to credit rating agencies and banks, and the whole idea that this is progressive needs to be re-thought? When banking and finance need a massive overhaul? When the alternative is significant tax hikes, and much of the public hates that idea, not just for selfish reasons but because of a mistrust of bureaucracy that the left needs to acknowledge is valid?

Progressives need to get outside the losing frame of higher taxes versus austerity. To do that will require new ideas. And new ideas require iteration, a groundbreaking of incomplete articulation that hopefully we can all build on.

Creating new frames will also require being inspired by all the great new ideas that have moved beyond the idea stage, and are actually being implemented in as-yet small-scale ways. If it exists, it’s possible.

Regenerative economy work happening all over the world is showing us what a new consensus approach — that is not right nor left nor Third Way bullshit — will look like. Here’s Gar Alperovitz articulating what it would look like coming from Bernie Sanders. And here’s my contribution to articulating what it might look like in Canada:

Childcare and the care economy

As with most progressive policies, part of what was missing here was the tangible, visceral description of how this would feel in our daily lives, and also how it was part of an overarching vision for moving beyond the extractive economy. I wanted to hear about how new co-ops in my community would bring parents and childhood educators together to provide the best for our kids. I wanted that wonderful story of childcare and elder care bound together, which we all love because it moves us closer to the community so many of us long for — while also addressing the very practical question of how we care for an aging population.

We can also focus on the ripple effects in our wider communities: how green jobs aren’t just in building solar panels, they’re in this kind of care, and teaching, and nursing, and the arts. As the Leap Manifesto points out, these are low-carbon sectors too. How this would give folks from Newfoundland who’ve relocated to the oil sands the option to stay in their home communities with good, meaningful work amongst the family and friends they love. How we could work with programs like Groundswell and RADIUS andStudio Y and all the ECE and employment training programs all across the country to prepare to launch networked care hubs so we’d learn from thechallenges in Quebec. How with this cooperative, community-centered model, these would not just be cogs in a bureaucratic machine that would inevitably alienate and disempower the people it was intended to serve.

By framing childcare in this way, as an economic booster, we’d not just re-articulate the true role of government in the economy, we’d also help address why this deserves the support of parents who want to stay at home, or have other family members care for their children. Having the option to do that isn’t just conservative traditional family values, it’s also feminist — it allows women to choose. One woman I talked to on the door raised important hesitations about subsidizing wealthy families while the combo of high housing prices and cheap childcare forced people into the labour market who didn’t want to be there. If not income splitting (one of the policies I heard the most confusion about) what can we do that appeals to people who want something other than outsourcing their domestic labour? Jumpstarting the economy by creating these local care hubs, where programs for kids of stay-at-home parents could also happen, is one place to start.

On energy and innovation

With the reality that even the overly modest two degree threshold means a lot of oil needs to stay in the ground, I want more than a promised review of Energy East. But, like more and more people inside and outside the climate movement, I also want more than the “no pipelines” argument.

A really solid Innovation Strategy that explained how we could use the care economy as above, and a decentralized, democratic renewable energy system, plus infrastructure building, and the very important and too-often-overlooked digital economy, and local food to build up local community wealth, would not only have checked a lot of boxes for a lot of people, it would have been visionary.

We could articulate how this would allow people to choose to join the next economy — the one that is stable and fair, versus the boom-and-bust resource economy the Conservatives padlocked us to. (The fact that so many people even in the mainstream media lamented the lack of emphasis on innovation to diversify the economy makes this obvious low-hanging fruit).

Those are some ideas — they’re some of the “what” of a potential new consensus. But much more important is the “how” — how do we develop policy in the “age of participation”? One of the more concerning things the NDP did was take down their member-developed policies and imply they were just suggestions. The party was very far away from the combo of expertly executed town-halls with a thoughtful process, in the style of Leadnow, and digital crowdsourcing à la OpenMedia that could bring more people into a less collapsible big tent. It’s just good practice — it’s ethical and smart — to bring policymaking closer to the level of the people it will most impact, who know best what works and what matters.

Moreover, it’s the only way forward for the left. When the right wins, it might be able to do so by being top-down, anti-democratic, and controlling. But that’s not what will inspire loyalty outside of the Conservative base, where folks look less exclusively to strong father archetypes.

(To be clear, this isn’t my indirect way of weighing in on whether Mulcair should stay. I think there are good reasons for him to stay, like the fact that he’s a great parliamentarian with some serious Question Period chops. I don’t know whether he should stay or go, and it’s not up to me to decide. It’s up to the members.)

The “how” of participatory democracy — which will include participatory budgeting and crowdsourced constitutions and liquid democracy — is far from fully articulated. In that sense, it’s not risk-free. And I welcome debate on what will and won’t work from what I’ve outlined here. But I’d encourage people to strive a little harder to present not just a critique, but an alternative. NDPers feel exasperated with much of the critique for some good reasons — like other partisans, they’re in the trenches everyday, dealing with the consequences of some of us having a too-comfortable echo chamber.

What would a coming-together rather than a falling apart look like, for people who care about social justice across all party lines? What would it look like to have “air-game” — high-level media and communications strategies — that matched and enhanced the model of engagement organizing and citizen-centric “ground-game,” which has re-set the bar both for parties and third-parties in the post-Obama era? Liberals of conscience should take heed too, if they want their support to be more than an anti-Harper default.

This is especially important in the wake of such a tough election. The best note I could end on is one of thanks to everyone who knocked doors and made phone calls and entered data and debated and fought and cried to end the Harper years. If it’s too soon now to talk concretely about what’s next, take the rest you so richly deserve. When you’re ready, I’m ready — and I hope more of your peers will be ready too.

Reilly Yeo is a public engagement specialist, co-creator of Groundswell, and lead convenor of OpenMedia’s crowdsourced policies Our Digital Future, Casting an Open Net, and Reimagine CBC.

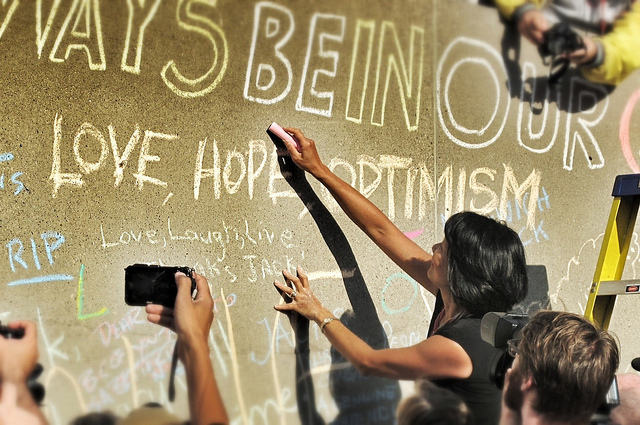

Photo: Kim Elliott