rabble is expanding our Parliamentary Bureau and we need your help! Support us on Patreon today!

So the headline is a bit melodramatic, but it’s essentially true. And a little melodrama seems to be necessary to capture people’s attention these days.

How else to explain the parade of opinion pieces that exclaim “Two weeks to save the planet!”? While it’s true that failing to arrest climate change would be a catastrophe outside the realm of human experience, it’s not true that one fateful decision will be made here in Paris.

Let me back up. After 20 years of failing to come to meaningful agreement on how to tackle climate change, the world’s 196 countries are trying a different approach. They have each submitted a document that indicates, among other things, how much greenhouse gases they intend to emit between now and 2030. Add together all these INDCs (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions, in the ever-expanding lexicon of the negotiations) and you have a pretty good idea of where the planet is going, climate-wise. A few researchers have done just that, and concluded that, if every country sticks to its plan, we’ll hit 2.5C to 3C of warming by the end of the century (and continuing to rise past then).

How bad is that? It’s bad. We’re at about 1C of warming now, and we’re seeing an uptick in heat waves, floods, and (ironically) droughts. The international community has committed to keeping warming below 2C, which will still result in significant sea level rise, disruptions to agriculture, loss of drinking water sources, and severe ocean acidification.

Small island states, concerned for their very existence, are pushing for a more ambitious target — 1.5C. The higher the temperature gets, the greater danger we run of crossing a “tipping point” — a runaway feedback mechanism that will take us to an unrecognizable, hothouse Earth.

So you might expect that countries would use the current talks in Paris to up the ante: make more ambitious pledges, reduce their emissions, etc. But they’re not doing that. It’s not even in the cards — the draft text of the agreement that they are wrangling over. Instead, the INDCs are going to be folded into the agreement in some manner, but without modification. And this is what has many activists tearing their hair out: countries are not meeting their own goals, they’re laying out plans to cook the planet, and it’s all going to be delivered with a bow and a smile.

There are, however, two important ways in which mitigation is being discussed here in Paris. Many developing countries (i.e., most of the planet) have delivered two-tier INDCs. The first tier lays out the climate actions they are already planning on implementing — the “unconditional” pledges. The second tier comprises emissions cuts they will make if the international community delivers financial support.

These “conditional pledges” explicitly link mitigation ambition (how deep will the emissions cuts be) to financial ambition (how much money will the rich countries deliver). So, as much as the rich countries would like to dodge the issue, finance is still front and center.

The second mitigation topic is the “ratchet mechanism”. Rather than seeing INDCs as the final word, we can view them as a first cut. The idea is that countries revise their commitments every five years or so, each time pledging to deeper emissions cuts. This incremental approach, it is hoped, will be less intimidating to countries which balked at taking on significant mitigation obligations all in one go.

The ratcheting mechanism is brand-new in this round of negotiations, and important aspects remain to be worked out, including how frequently it will happen, how the new rounds of commitments will be assessed, and whether they will be subject to review before being accepted.

These issues are all important; with luck, they might provide a pathway to deeper emissions cuts in the future which would get us closer to the UN’s 2C goal. But they are only one piece of a large and complex puzzle.

Solving climate change is a challenge that requires changes at every level — local, national, and international; in every business; and in our personal habits. Only a few of those decisions will be made here in Paris. The rest are up to us.

Neil Tangri is currently a PhD student in climate science at Stanford University. Previously, he directed climate campaigns at the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives.

rabble is expanding our Parliamentary Bureau and we need your help! Support us on Patreon today!

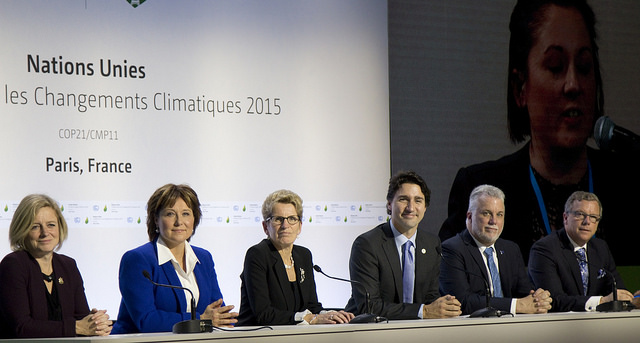

Image: Flickr/bcwebphotos