Thousands of federal government employees, from summer students to managers, have been underpaid, overpaid or not paid at all since the government began using the Phoenix pay system in 2016. Justin Trudeau’s Liberals implemented the payroll system introduced by Stephen Harper’s Conservatives, despite warnings about potential problems.

Past and current federal employees rabble has spoken to in recent weeks all express deep conviction for their work. They feel betrayed by an employer who does not pay them properly or, in their view, admit responsibility for the problem. Some expressed frustration with the unions that represent them and wonder what more could be done to solve the situation.

In this series, rabble.ca takes a broader look at Phoenix: the background of the problem; the people affected by it; the responses from unions, and what solutions may be possible.

Since the federal government started using the Phoenix pay system to pay their workers, hundreds of thousands of civil servants have been thrust into financial uncertainty. Frustrated by an impersonal system they say does not address their concerns, and a lack of clarity about when these problems will be fixed, these employees have been forced into situations many never anticipated. Adult children have asked retired parents to pay for their mortgages. Employees spending more time at work trying to make sure they get paid than doing their official jobs. Parents are unsure about if they can afford child care.

While they wait for answers, they live with questions about when and how this problem will be fixed — or if that’s even possible.

“It’s just always going to be a cloud over top of our heads”

For Christine Harrington, processing employment insurance claims as part of a specialized unit of Service Canada in Kamloops, B.C. was the job of a lifetime. She responded to unique situations, whether created by the introduction of new government bills or natural disasters, like the Fort McMurray wildfires in 2016.

“Sometimes we’d have to fly by the seats of our pants and figure it out as we went, but it was always working towards making sure that clients were in a good situation,” said Harrington, who considers the response to the Fort McMurray wildfires a career highlight. A task force was assembled so claims were processed within days, not weeks. When people needed help, someone was available to talk with them.

But a few months later, pay problems plagued Harrington’s worklife: “You could never get anyone on the phone,” she said, describing her attempts to reach people at the Phoenix call centre in Mirimachi, New Brunswick.

She “took a lot of pride in working for the government,” she said, but now struggles to talk about her difficulties with Phoenix without getting nauseous or anxious. She’s fearful to return to her job because she doesn’t know if she’ll get paid.

Harrington started at Service Canada in October 2013. In April 2016, just as Phoenix was implemented for her, she took a four-week leave because of back pain. She returned gradually, but was paid at her normal, full rate. Her overpayment grew. By the time she was working full-time, it was $5,000, she said.

In July, she stopped being paid altogether. Nobody could explain why. This continued for 10 weeks. She received some emergency grants. In September, she “randomly” got a payment for $15,000 she said.

Harrington estimates she put in 28 requests to Phoenix about her concerns. Most of her communication with the call centre has been through voicemail.

Instead of doing what she loved, most of work hours were spent trying to make sure she was getting paid properly.

She cried at work every day and fought headaches and nausea. She battled insomnia, and for the first time in her life, high blood pressure.

“I was crumbling. I crumbled.”

Harrington finally took a medical leave in October 2016, although she said her doctor wanted her to take one earlier. She’s not receiving pay now, and is no longer eligible for employment insurance. Before, she was the main breadwinner for her husband and three children. Her husband, a satellite technician, bought the company where he works.

Harrington contacted her union, the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC). They filed a grievance. But in Harrington’s mind, there isn’t much more that can be done. Phoenix’s problems are too big, she said.

Her problems won’t end anytime soon, either. She estimates her total overpayment stands at about $20,000, an amount she’s been told she can pay back in 10 per cent increments from each paycheque when she returns to work.

“It’s ridiculous that people are going to have to live under the cloud of Phoenix when it’s all gone,” Harrington said. “It’s just always going to be a cloud over top of our heads.”

“No other employer would ever have been allowed to not pay their employees for 10 weeks,” she said. “That wouldn’t be allowed, and for some reason, because it was the government it was allowed. And it’s really sad.”

‘Your money is being held for ransom, and you can’t even talk to the kidnapper’

The hardest part about Sherie Gladu’s job planning recreational programs for the Township of St. Joseph in northern Ontario is worrying about her last job at Parks Canada.

Gladu left Parks Canada in May, after being with the agency since 2011. She began working in groundskeeping and maintenance. In 2015, she started planning activities at national historic sites Fort St. Joseph and the Sault Ste. Marie Canal. That’s one of the things she loved most about her workplace, she said: opportunity for advancement.

But it was hard to love her job when she didn’t know if her employer would pay her enough to cover the cost of commuting to it.

Problems with Phoenix weren’t the only reason Gladu left her job; she also wanted a better work-life balance. But it motivated her to start looking sooner than she anticipated.

“It just was one of those things that sort of beat down on you so much that you just start looking.”

Gladu and her colleagues switched to Phoenix in May 2016. Other federal employees had told them about problems, but they “were crossing our fingers that they had gotten some of the bugs worked out.”

They hadn’t.

In June, Gladu’s paycheques stopped. This lasted for six weeks. She watched her savings dwindle, and began to wonder how she would afford daycare for her two school-aged children.

She received an emergency salary advance of 60 per cent of what she was owed.

Her pay resumed in August. But she was being paid as if she was still a maintenance worker, so her paycheques were hundreds of dollars less than what they should have been. This continued throughout the fall. Gladu estimates the government owes her at least $2,000, before taxes, for money lost during this time.

In November, she began being paid for the right position, but she was paid as if she was in her first year in the role, not the second. This issue was only resolved shortly before she left.

Before Phoenix was introduced, Gladu never had problems like this with receiving her pay, she said.

After she left Parks Canada, she received a letter telling her she owed the government $500 in backpay. Gladu kept the letter and said she lives with the concern they might try to regain the money from her.

Gladu said she has 11 formal complaints in the Phoenix system, half unresolved. She’s called the service centre in Miramichi, but hasn’t been able to speak with “anyone who knows anything about what’s happening with (her file).” The lack of personal communication, she said, is the biggest problem with the system.

“Your money is being held for ransom,” she said, “and you can’t even talk to the kidnapper.”

Gladu was a member of the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC). She said she reached out to the union, but the responses and updates were vague. She would have gladly gone on strike over issues with Phoenix, she said.

“If we don’t fight, we’re sure to lose,” said Gladu. “The squeaky wheel gets the grease, right? We weren’t squeaking. We weren’t squeaking near enough.”

‘This isn’t just a normal transactional issue that’s annoying’

Jennifer Carter works as a manager with Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada in Ottawa, making sure funds are distributed properly to different organizations. For seven months in 2016, she didn’t get paid.

“I used to joke that I was volunteering,” said Carter, who has worked with the federal government since 2000. “But I actually still showed up every day because it’s too important to not.”

In February 2016, Carter returned to work after more than a year on sick leave, a result of workplace burnout, stress and depression. She assumed she was getting paid properly — until her bank called her in June to say her mortgage had bounced.

Fortunately, she has good credit, and her retired parents were able to help her.

“Coming back after a mental-health leave, you can imagine how much fun this was,” she said. Colleagues have told her she must be doing better if this situation hasn’t broken her.

Carter said she was not paid at all from February to August 2016. Payments resumed for two weeks — and then stopped. She’s getting paid now, but deductions haven’t been calculated properly.

She estimates she owes at least $7,000 in overpayments as a result, but the government’s “taking their sweet time” asking for it back. “I run my life hoping eventually they’ll send me a bill and I can afford to pay them.”

Carter said her boss was amazing, and did all he could to fix her situation. She tries to do the same with her staff, directing them to staff dedicated to helping people with Phoenix-related problems. Solutions, though, seem hard to find. Her union, the Canadian Association of Professional Employees (CAPE), did little more than send her grievance forms to complete, she said.

She said responses from the federal government lack empathy or understanding of how people are being affected.

“This isn’t just a normal transactional issue that’s annoying. This is something that’s impacting people’s lives,” said Carter. She knows of people who are choosing not to buy cars because of Phoenix, or can’t afford to send their children who have disabilities to specialized schools.

Government employees make less than people realize, she said. Private companies would face lawsuits for not paying their workers, but government employees are essentially told to “suck it up,” she said.

“My bank doesn’t ‘suck it up’ so good,” she said. “My credit card company doesn’t like it very much.”

Still, Carter firmly rejects the suggestion she and her colleagues should stop coming to work because of the pay problems. It’s the job of public servants to show up and work, she said. All of her staff have had problems with Phoenix, too — but none have stopped coming to work because of this, she said.

She’s heard colleagues say they wish they could stop coming to work but can’t “because people really believe in their jobs.”

Meagan Gillmore is rabble.ca‘s labour reporter.

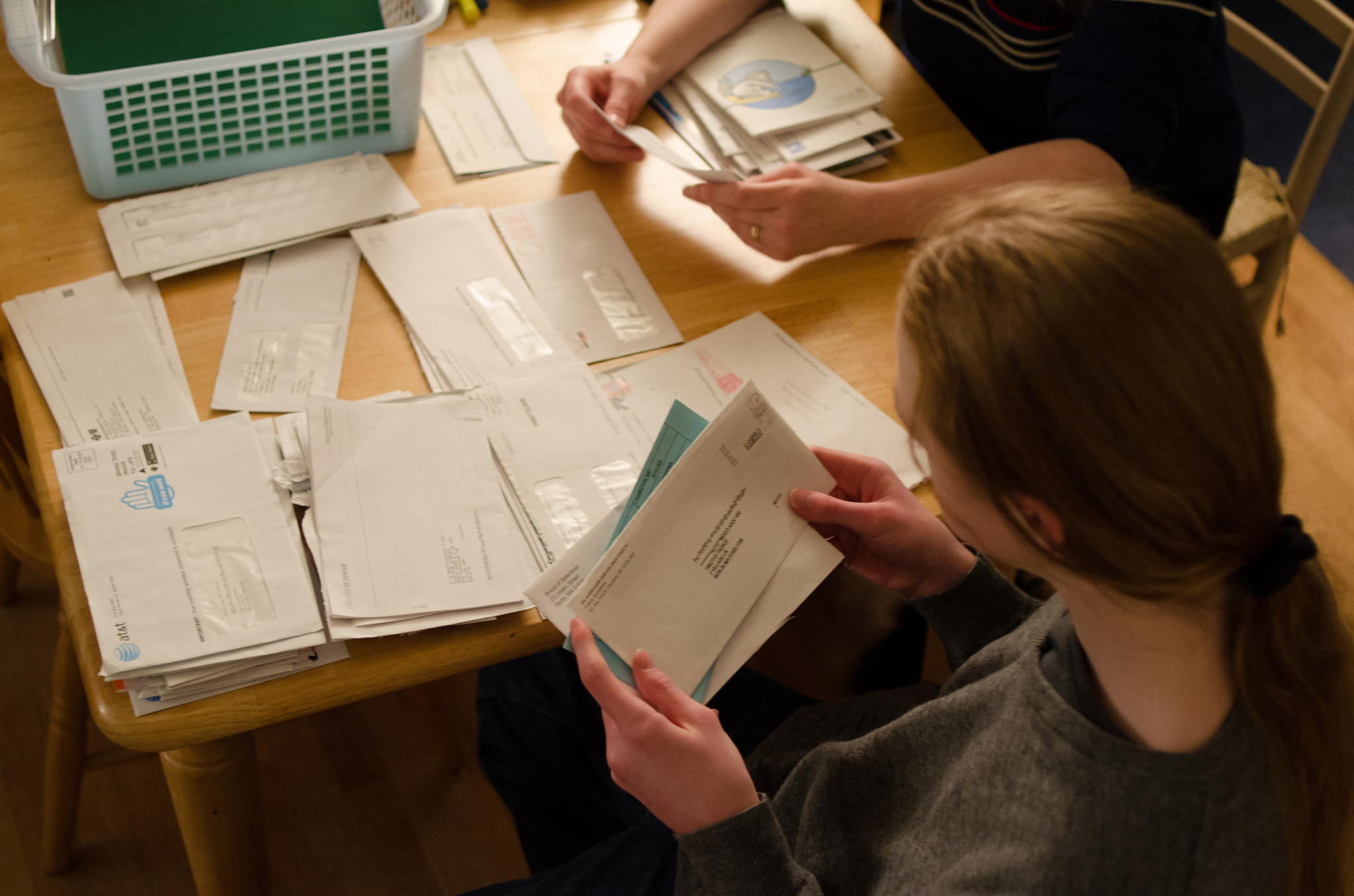

Image: flickr/qwrrty

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.