The movement for women’s suffrage in Ontario began in 1844, when the colonial government of the day passed a law making it illegal for women to vote — a law that was not reversed until 73 years later, in 1917. Tarah Brookfield’s book, Our Voices Must Be Heard: Women and the Vote in Ontario, chronicles both the movement’s triumphs and its exclusions of Black and Indigenous women. Suffragism was not only confined to the growing townships of Southern Ontario, but spanned the whole province. In this excerpt, Brookfield describes the rise of the suffrage activism in what is now Thunder Bay.

Another energetic addition to the Ontario movement emerged in Port Arthur-Fort William (later Thunder Bay), a twin city on Lake Superior. Originally a fur trade post and mining town, it had become a key stop on multiple railway lines, resulting in rapid development and modernization. Between 1901 and 1911, the combined population jumped from 7,211 to 27,719, making it Ontario’s fifth largest city. As early as 1899, the Weekly Herald and Algoma Miner noted local interest in suffrage and described the cause as a matter of human rights.

Led by Dr. Clara Todson, Mary J.L. Black (1879–1939), and Anne J. Barrie, reform and suffrage agitation was a robust force in the twin city. Todson, one of the region’s first female physicians, was a recent arrival, having moved from the United States, where she had been active with the Illinois Civic Equality League. Jumping into local activism, she became president of the newly formed West Algoma Equal Suffrage Association.

Though she lived in the city for only three years before her mother’s illness forced her to return to the United States, Todson quickly gained a reputation as a celebrated reformer whose frequent letter writing called upon local and provincial politicians to improve civic life through support of temperance and suffrage.

Mary J.L. Black, a librarian, was renowned for transforming the local library from a neglected facility to a celebrated hub of culture and education in the predominantly working-class community and for being the first female president of the Ontario Library Association. Anne J. Barrie, a musician noted for having written the song “Lil Suffragette,” made up the trio, leaving behind a scrapbook that chronicled the West Algoma campaign.

Their endeavours included collaboration with the CSA on municipal voting rights for married women, rallying around female school trustees, channelling energy toward the provincial franchise campaign, and fighting anti-suffrage efforts at home. The Fort William Daily Times-Journal devoted a regular column to the association’s affairs.

Todson, Black, and Barrie were single and childless — it is thought that Todson and Black never married and that Barrie was widowed. Consequently, they probably enjoyed more liberty than the average wife or mother, but it also became a conspicuous identity to defend against opponents who equated suffrage with the end of marriage.

Tackling this prejudice, Todson argued the opposite: poverty and social evils were what drove women to seek alternatives to marriage. If female voters forced the legislature to make economic and social improvements (such as the reduction of poverty, alcoholism, and prostitution), Todson predicted that marriage rates would soar and result in more stable families.

In the meantime, being unmarried brought Todson, Black, and Barrie themselves a step closer to accessing municipal voting rights, but it is unknown whether they met the property qualifications. What information has survived about their residences and livelihoods suggests that in the early twentieth century, Todson shared a home with a male relative, Black’s wages were precarious, and Barrie boarded in the household of the local jailer. Even among these leading women, economic security could remain elusive.

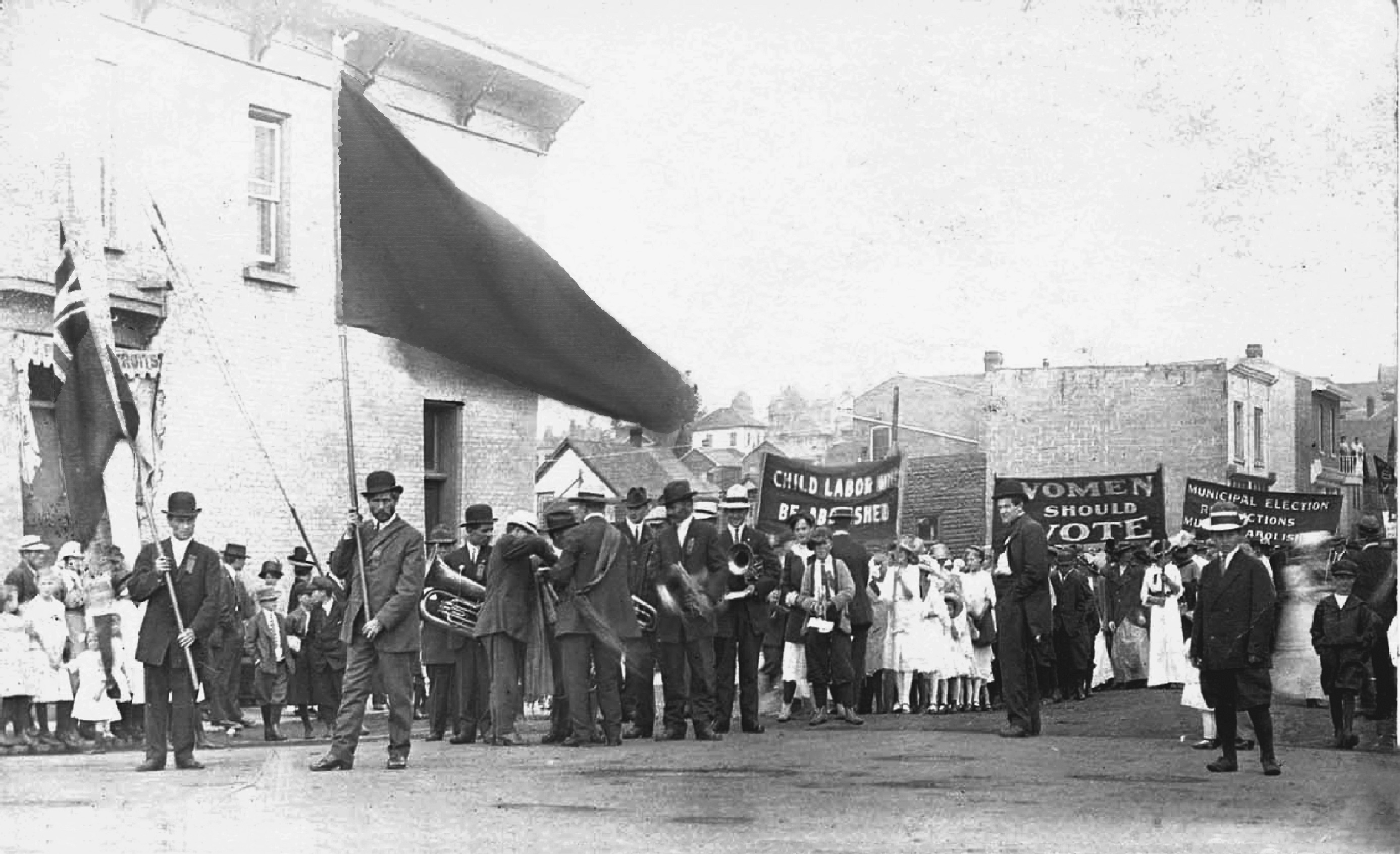

Port Arthur-Fort William’s suffrage cause was aided by sizable support from members of the Finnish community, many of whom were also embedded in the local labour movement and socialist politics. In Finland, women had been enfranchised in 1906, a product of their political organizing since the late 19th century and the success of legislative reforms sought by socialists and anti-czarists alike, who pushed for universal suffrage in the early 20th century. Finnish women were the first to be enfranchised in Europe and the first anywhere in the world to hold elected office. Drawn to cheap land and industrial employment, many Finns immigrated to Canada between 1900 and 1914.

For women, migration meant relinquishing hard-fought voting rights and returning to suffrage activism in their new homeland, primarily through socialist organizations. Such was the case of Sanna Kannasto (1878–1968), a recruiter for the Socialist Party who, after a brief sojourn in the United States, moved to Port Arthur with her common law husband. Much like her Anglo counterparts in Toronto, Kannasto pushed the Socialist Party to focus on issues related to gender as well as class. In addressing women workers, she spoke of the need for suffrage, birth control, and equality within marriage.

Kannasto concentrated on the Port Arthur-Fort William region, enlisting workers in mining and lumber camps, but she participated in at least five national recruitment tours. Her travels gained the attention of the RCMP, who labelled her a “dangerous radical” and threatened deportation. Even among the less radical Finns, suffrage was widely supported. “Equal rights for everyone regardless of sex” became a rallying cry of the Canadan Uutiset, a right-wing Finnish newspaper published in Port Arthur that came out in favour of women’s suffrage in 1915.

It is unknown whether the “radical” Kannasto or other Finnish suffragists interacted with the “respectable” ladies of the West Algoma Equal Suffrage Association, or if language barriers and political difference kept the two communities apart.

One clue to possible overlap appears in the suffrage column and women’s page of the Daily Times-Journal, which sometimes voiced support for putting the ballot in the hands of working women. The efforts of dedicated, hard-working women such as Kannasto, Todson, Black, and Barrie in Port Arthur-Fort William demonstrate that the suffrage cause was alive and well outside of Toronto. They did not work in isolation. Railways connected northern suffrage enthusiasts to national and transnational networks of speakers and resources.

Back in Toronto, the CSA continued to lobby for the municipal enfranchisement of married women and for the provincial vote for all women. Between 1905 and 1906 alone, new MPP defenders of women’s suffrage presented seventy-two petitions on municipal voting to Premier James Whitney, who rejected them all. Thus, the 1906 endorsement of Toronto mayor Emerson Coatsworth was welcomed when he chaired a public meeting. “I wish you all had votes,” Coatsworth thundered to the audience of 75 women and a few men.

Speaking at the same event was Dr. Willoughby Ayson, a female physician from New Zealand who argued that her dominion’s enfranchisement of Māori and white women thirteen years earlier had elevated the colony, not doomed it: “Men there prefer their wives and mothers and sisters shall be their equals, and not their subjects.” Moreover, she added, the failure to revoke the measure demonstrated widespread public satisfaction with it.

No argument seemed to shake the prejudices at Queen’s Park, however. Even a March 1909 petition with nearly 100,000 signatures, delivered to Whitney by a five-hundred-person delegation led by Stowe-Gullen, produced no action. Denison, Johnston, and Gordon, plus representatives from the WCTU, Women’s University Clubs, the Women’s Teachers’ Association, and the Medical Alumnae of the University of Toronto, had joined male allies School Inspector James L. Hughes, Unitarian reverend R.J. Hutcheon, and Council Controller Horatio Clarence Hocken to head the delegation.

For the first time, there was also significant representation from the Toronto District Labour Council (TDLC), the Socialist Party, and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. To Stowe-Gullen, the event disproved the government’s tired refrain that suffrage was of interest only to “a few faddist women.” To ignore the demands of thousands was “tyranny,” she declared. “Would they stand for this injustice for themselves?” Stowe-Gullen asked. “Should they stand for it for their mothers, wives and daughters? No race or class or sex can have its interests properly safeguarded in the Legislature of any country unless represented by direct suffrage.”

Excerpted with permission from Our Voices Must Be Heard: Women and the Vote in Ontario by Tarah Brookfield (UBC Press 2018).

Image: Finnish Canadian Historical Society

Help make rabble sustainable. Please consider supporting our work with a monthly donation. Support rabble.ca today for as little as $1 per month!