In 1976, when Vancouver hosted the first UN Conference on Human Settlements, B.C.’s lower mainland was paradoxically embroiled in two housing controversies: a squatting community on the North Shore, known as the Maplewood Mudflats, was demolished by civic authorities in 1971, and residents of the working-class Bridgeview neighbourhood along the Fraser River were fighting for basic amenities. This excerpt from Jean Walton’s new book, Mudflat Dreaming: Waterfront Battles and the Squatters Who Fought Them in 1970s Vancouver, recounts how housing activists came together to create a citizen-based conference that ran simultaneously with the UN Conference. During a time when housing crises in Vancouver and elsewhere are mounting, Walton’s book is an important reminder that if gentrification isn’t new, then neither is resistance to it.

In 1972, the year I started volunteering down on the Bridgeview flats, and the year the Maplewood Mudflats documentaries were screened for their first audiences, a seed was planted by Canadian delegates halfway around the world at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm. The Stockholm meetings should be followed up, the Canadians proposed, by another conference focused exclusively on the global problem of how to ensure that everyone in the world had a decent place to live. Planning began almost immediately for what was to be the first UN Conference on Human Settlements, to be held in Vancouver, British Columbia.

During those preparatory years before what came to be known as Habitat, Vancouver was itself caught up in civic debates about development, livability, and an alarming housing shortage in the face of a rapidly increasing population. What better place to host a conference on the subject of adequate shelter for all? Could Vancouver be a model city for the world to consider, with its active port, its majestic views of the nearby mountains, its industry mixed with residential neighbourhoods, its radiant beaches, its recent commitment to “citizen participation” in development schemes for the city’s future?

Vigorous citizen involvement had recently averted the construction of a massive freeway project and a waterfront scheme that would have wiped out Vancouver’s Chinatown and most of an historical residential district. At the provincial level, the newly elected Barrett government had just implemented an Agricultural Land Reserve, designed to freeze the sale of farmland for commercial, industrial, or residential development — an early recognition of how crucial it was to protect and promote local food production.

City planner Harry Lash was working on an immense planning document, “The Livable Region,” whose goal was to “manage the growth of Greater Vancouver” by finding out from the public “what livability means; abandon the idea that planners must know the goals first and define the problem; ask people what they see as the issues, problems, and opportunities of the region.”

NFB Filmmaker Chris Pinney and his social animators in Surrey were well aware of the emphasis being placed on citizen involvement in Lash’s plans for Vancouver and its outlying municipalities. If livability was to be emphasized as a goal in the big city, part of Pinney’s job was to make sure the less desirable aspects of urban life did not get shunted off to the southerly suburbs, where local politicians, like those on Surrey council, were all too eager to cooperate with developers seeking to make a buck on the refineries, landfills, and industrial parks that Vancouver did not want in its immediate backyard. And Bridgeview was the case study for this complex problem of livability in an urban context.

Surrey Mayor Bill Vander Zalm had made it clear that he was no Harry Lash, as evidenced in an interview in the Surrey-Delta Messenger. When asked whether he thought the municipality communicated adequately with the taxpayers, he replied, “What the people really seek more than anything else is leadership,” or to be more specific, “a council that is able to make their decisions for them rather than all of this ‘input’ we hear so much about.”

The Challenge for Change animators’ work was truly cut out for them. As soon as the UN Conference on Human Settlements became public knowledge, Pinney saw it as a prime venue to capture a global audience for our very local sewage problems down on the Fraser River flats.

Meanwhile, in Vancouver itself, a kind of People’s Forum was being planned for Jericho Park. This was to be a more accessible, citizen-based conference that would run simultaneously with the UN conference. If Vancouver city officials were hesitant at first to host the official conference downtown, given the cost of heavy security for such a high-profile gathering of international delegates, the Parks Board was even more reluctant to give the green light for a gathering of potentially unruly hippies in Jericho Park, which had already hosted the launch of Greenpeace actions and rock concerts. But through the tireless lobbying of Vancouver producer, filmmaker, and visionary Al Clapp, the People’s Forum received the go-ahead. According to Lindsay Brown,

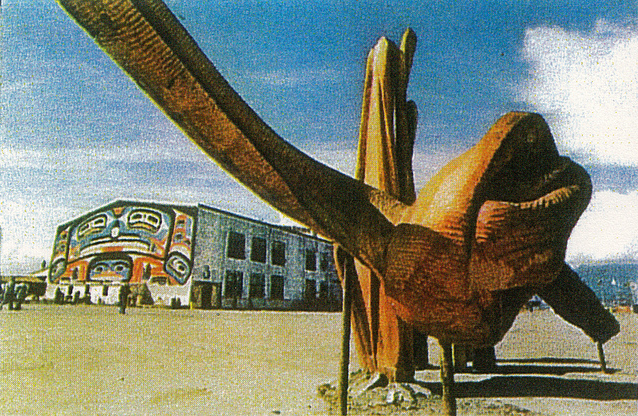

With only five months’ notice, [Al] was able to organize 11,000 volunteers and unemployed students and tradespeople on work grants to refurbish the [park’s] five art deco [seaplane] hangars into a beautiful village that was the earliest and probably still best example of public recycling in Vancouver’s history. The hangars were turned into two beautiful amphitheatres for plenary sessions and performances, a hall for NGO exhibits on housing and sustainable technologies, and a massive social centre featuring the longest standup bar in the world entirely handmade with yellow cedar found on the beaches.

Clapp had visited the Maplewood Mudflats in the early ’70s and, in fact, had covered the squatters’ plight for Vancouver’s local media outlets. He was friends with Ian Ridgway, Dan Clemens, and the Deluxe Brothers “family” of carpenters and builders. They had collaborated on the Pleasure Faires, and now Dan and Ian were among the “unemployed” artists and craftspeople Clapp hired to transform Jericho Park’s seaplane hangars into a showcase for their West Coast salvage aesthetic.

“Ian had hangar number seven,” Dan Clemens recalled. “I had hangar ten. As I remember, it was pretty amazing what we built. Ian built the ‘world’s longest bar.’ Seven hundred feet.” I couldn’t fault Dan for exaggerating the length of the bar, which was described elsewhere as snaking through hangar seven, Habitat Forum’s “social centre,” for almost 208 feet. It was the solidity, the beauty, and the bountifulness of the bar that was memorable.

As left-leaning planner David Gurin wrote,

Two series of meetings were held in Vancouver, British Columbia, in June. One was the official United Nations Conference on Human Settlements that considered proposals which if made specific, and if implemented with lots of money could affect the way people live in cities and villages around the world. However, with the Arab-Israeli conflict lacerating the UN the specifics and the dollars from the rich countries are not likely to be available soon. Thus, the more realistic approach of the unofficial Habitat Forum became all the more interesting.

The Habitat conference was rife with tensions from the start, most of them related to the stark economic divide between developed and developing nations — a conflict that was endemic to the United Nations in general. The themes of development versus livability, unsavoury sanitary conditions, relocation schemes, endangered ecological sites, and contested human settlements that were playing out locally on Vancouver’s tidal fringes found full-blown analogues on the global scene.

Uppermost in the minds of nervous Vancouver city officials, and in the press coverage of the conference, was the escalating international discord around Israeli-occupied — or disputed — territories following the Six-Day War of 1967. Maybe it was inevitable that a conference devoted to the global problem of “human settlements” would be coloured by these very prominent “settlements” on the West Bank.

If the leaders of the developed nations wished to keep discussion focused only on the remediation of problems like housing shortages, access to services, and the need for clean water, seeking to treat the situation from the point of view of paternal benevolence — extending a helping hand to the needy — others, like the Group of 77, had a different approach in mind.

The Group of 77 was a coalition of developing countries, formed in 1964 with a view to improving their role in global trade. When Habitat took place, the UN had just adopted a set of proposals put forward by the Group, called the New International Economic Order. Habitat delegates who represented the Group of 77 worked vigorously to foreground the principles of the New International Economic Order in the Vancouver Declaration, the official document that had been drafted by the UN and was then heavily revised during the course of the conference.

From the point of view of a developing nation, you could say that it was not possible to separate the question of adequate housing for all from the determining factors of geopolitical forces: colonialism and neo-colonialism, capitalist exploitation, apartheid, and the like. Who had the authority to make decisions about how vast populations were to be safely and humanely housed in the locality that most suited them? Should the development of the world’s cities — where the question of habitation was most pressing — be left to the developers, planners, and multinational corporations? But what of the millions of people who had, in the direst circumstances, made do for themselves? As Habitat’s Secretary-General Enrique Peñalosa pointed out, in his own country (Colombia), “90% of all housing was constructed, not by the government or by the private sector, but by the poor themselves — often against the law.”

There were forum papers on appropriate economic growth, the future of metropolitan areas, human settlements and education, and Indigenous building methods in the Third World; workshops on children and human settlements, hard core poverty, and quality of life for the handicapped; discussions about the arts, recreation, energy, and “the role of tall buildings”

in human settlements; a prospectus for a “Self-sustaining Neighborhood-centered Community Development Corporation for Collection and Recycling of Household, Apartment House and Business Waste;” and a paper on the “Impact of Space Colonization on World Dynamics.”

Presentations were given on national settlement policies in Africa, Mexico, and Southwest Asia; urban renewal in London and Liverpool; and the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry in Yellowknife (the latter by the president of the National Indian Brotherhood). There was a session on women’s role in shaping the urban environment. Considerable attention was also paid to the existence of squatters’ communities across the world, and the question of how best to support their efforts to help themselves. Most controversial, it seemed, was the emphasis placed on public ownership of land — both in terms of how that land should be utilized within a given country, but also in terms of a state’s control over land that might be owned or occupied by foreign interests.

The final version of the Vancouver Declaration addressed public ownership of land head-on. Since “private land ownership” was a “principal instrument of accumulation and concentration of wealth,” contributing to “social injustice,” public control of land use was “indispensable to its protection as an asset and the achievement of the long-term objectives of human settlement policies and strategies.” Governments must maintain “full jurisdiction and exercise complete sovereignty over such land with a view to freely planning development of human settlements throughout the whole of the natural territory;” moreover, land as a natural resource “must not be the subject of restrictions imposed by foreign nations which enjoy the benefits while preventing its rational use.”

As if to drive home the point, the next section insisted that “in all occupied territories, changes in the demographic composition, or the transfer or uprooting of the native population, and the destruction of existing human settlements in these lands and/or the establishment of new settlements for intruders” was “inadmissible;” policies that violated the protection of heritage and national identity “must be condemned.”

Among the general principles of the declaration was the affirmation that “every state” had the “sovereign right to rule and exercise effective control over foreign investments, including the transnational corporations, within its national jurisdiction, which affect directly or indirectly the human settlements programmes.” The establishment of settlements in “territories occupied by force” was illegal and condemned by the international community — “however, action still remains to be taken against the establishment of such settlements.” Highest priority was to be placed on “the rehabilitation of expelled and homeless people” who had been “displaced by natural or man-made catastrophes, and especially by the act of foreign aggression.”

Excerpted with permission from Mudflat Dreaming: Waterfront Battles and the Squatters Who Fought Them in 1970s Vancouver (New Star Books).

Help make rabble sustainable. Please consider supporting our work with a monthly donation. Support rabble.ca today for as little as $1 per month!