In her powerful anti-war statement, The Crisis of German Social Democracy, Rosa Luxemburg famously paraphrases Friedrich Engels (or more likely Karl Kautsky): “Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regression into barbarism.” These words, written while Luxemburg was imprisoned in 1915, and the stark realities they suggest, come back into harsh focus as governments and businesses re-tool in the context of COVID-19. And as diverse working-class communities struggle to meet very basic needs.

As the coronavirus pandemic spread, and notably as numbers of people impacted grew in Europe and North America, it became increasingly apparent that the route to barbarism has already been given some consideration by certain politicians and pundits. Indeed, expressions of barbarism have kept pace with the awful spread of the coronavirus.

At the same time, inspiring examples of a new “social” are being built, basket by basket, bag by bag, as communities of exploited and oppressed people work to care for one another. Mutual aid groups providing supports within communities, workers forced to work under horrible circumstances having each others’ back and organizing strikes and walkouts, neighbours communicating and collectively readying to withhold rent from their landlords.

These are signposts at a crossroads. COVID-19 has brought into focus struggles always underlying capitalist societies. And the stakes are perhaps being raised on a broadened scale.

Exterminist nightmares

It took only a few weeks under the pandemic for extremist narratives, at times called ecofascism or more simply fascism, to present the pandemic as a sign that humanity (undistinguished by class, status, colonial history, etc.) as a whole was the actual virus threatening the planet. This was referenced by decreased emissions, reduced pollution, clearer waters in Venice and the apparent return of some species to habitats near cities.

All of an indistinct “humanity” was blamed for the activities planned, controlled, demanded and pursued by economic powerholders and socially prioritized and protected by their state defenders (such as a Canadian government pushing and promoting oil and gas extraction on Indigenous lands). Not results of a specific, destructive social system, and its structures of inequality, exploitation and accumulation — as climate change, habitat destruction, species loss, pollution, etc. are.

In a very short period of time the “humanity is the virus” narratives (with their implications that many of us could simply be done away with to make things better) were added to and “operationalized” by public figures, including the current president of the United States, about how many people could be sacrificed in order to “save the economy” and return to business, something like a capitalist “normal.”

Trump himself raised this query in a press conference in March. In a tweet (his preferred mode of communication) of March 22, Trump asserted the same (in all caps):

“WE CANNOT LET THE CURE BE WORSE THAN THE PROBLEM ITSELF. AT THE END OF THE 15 DAY PERIOD, WE WILL MAKE A DECISION AS TO WHICH WAY WE WANT TO GO!”

Of course, Trump is only the tip of a barbaric iceberg. As the New York Times reported at that time: “Some Republican lawmakers have also pleaded with the White House to find ways to restart the economy, as financial markets continue to slide and job losses for April could be in the millions.” The Times went on to say: “at the White House, in recent days, there has been a growing sentiment that medical experts were allowed to set policy that has hurt the economy, and there has been a push to find ways to let people start returning to work.”

On Fox News’ America’s Newsroom, Trump’s top economic adviser Larry Kudlow was perhaps even more explicit: “But the president is right. The cure can’t be worse than the disease, and we’re gonna have to make some difficult trade-offs.” One might ponder the “we” invoked here and who would have to give and who might receive in this particular trade deal.

Texas Lieutenant-Governor Dan Patrick went on Fox News to say that grandparents would be willing to die to save the economy for their grandkids. He complained that the country would collapse if the shutdown went three months.

To be sure, capital was getting itchy to go on pursuing profits. Also in a tweet, the senior chairman of Goldman Sachs, Lloyd Blankfein stated impatiently: “Extreme measures to flatten the virus “curve” is sensible-for a time-to stretch out the strain on health infrastructure. But crushing the economy, jobs and morale is also a health issue-and beyond. Within a very few weeks let those with a lower risk to the disease return to work.”

Political pundits immediately took it up, circulating their own morbid metrics and death to economy ratios. One Toby Young, secretary-general of the Free Speech Union, and self-professed “progressive eugenicist” (and self-defined “toadmeister”) applied his calculus to criticize the economic assistance plan floated by the U.K. Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak. Once more taking to Twitter to expound his version of barbaric mathematics, Young, on March 31, tweeted: “First, that the cost of the economic bailout Rishi Sunack [sic] has proposed is too high. Spending that kind of money to extend the lives of a few hundred thousand mostly elderly people with underlying health problems by one or two years is a mistake.”

That bit of “progressive eugenics” was followed up with an additional tweet by way of “explanation”: “That may sound callous, but in normal times the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) puts an upper band of £30,000 on the cost of adding one quality-adjusted life year (Qaly) and by that metric we’re massively over-spending.”

The pandemic is yet another excuse to justify neoliberal cuts to social services. Not to increase public health funding, but to gut it further.

A different path

If the road to barbarism is being mapped in glimpses like these, we should take some heart and much inspiration, from the organic socialism emerging from communities far and wide to care for one another, but also in collectively organizing new alternatives to pre-pandemic business as usual. Not to restore a “normal” that was already deadly, but to forge new, different, better, possibilities.

Mutual aid and solidarity, long watchwords of socialism of various types, have become increasingly heard calls for community-based responses to crisis, and perhaps foundations for social relations beyond crisis. Groups of people have been preparing and distributing solidarity packages of essential items (food, clothing, hand sanitizers, etc.). They have been making masks for health-care workers.

A number of mid-range or transitional demands have also been raised along with more radical or transformative initiatives. Transitional demands include louder calls for rent moratoriums or cancellations, paid leave and universal income.

These are being raised alongside organizing efforts like rent strikes, workplace strikes and walkouts, sick-ins, etc. in numerous cities and industries. Wildcat strikes have hit big capital players like Amazon, McDonald’s, Target, Kroger, Perdue Farms and more.

All over, people are asking about the real nature of work in this economy, beginning to question ownership, of homes and workplaces, on a broader scale, questioning profit and property as organizing principles and as social and life maxims. Cracks in ideology.

Not, perhaps, on a mass scale yet, but in ways that suggest these questions have moved from something that could be denigrated as being on the margins of the Left (as indeed they were even as the COVID crisis was emerging in North America, if one recalls the attacks on social democrat Bernie Sanders during the Democratic debates and primaries) — to at least a degree.

And the more radical Left — the socialist Left, the anarchist Left — has an opening to be sure, to take up and build on these connections in much changed social, political and environmental contexts. Indeed, the Left will need to show that it can support real world efforts to build on and extend emerging projects, to help make them mainstream and multiply them; to support BIPOC who are already, and have long been, doing that work — to take direction and learn from them. And that includes confronting racist, anti-Chinese, rhetoric and actions; to fully address the colonial character of capitalism (and their place as settlers), as the exterminist narratives show again, and to strive to make sure that socialism is finally decolonial.

These are crucial challenges. These provide potential routes to socialism in practical and meaningful ways. Ways away from the option of barbarism that capital and states are too willing to impose on us. Nothing is assured of course, and real outcomes will be the results of our capacities to organize — to fight and to win.

Conclusion

Capitalism has always been barbaric, it has always carried barbarism within its system logic. And states have been ready instruments of barbarism. Those most oppressed within it — Indigenous people, Black people — have always known this and have clearly identified it. And the brutality of neoliberal capitalism, with its attacks on the working class, poor and racialized communities, and cuts to resources needed by the working class (health care, housing, social welfare, transit, etc.) have contributed mightily to the current pandemic crisis and its most harmful impacts.

Crossroads can provide a certain clarity, especially to those who have not seen it or who have not been able to name it. In the explicitly exterminist economic assessments being expressed by business leaders, mainstream media figures and politicians in ruling parties, we can see how capital and state actors actually regard the working class, the exploited and oppressed.

If anything, the pandemic has shown that a society organized around production for profit and accumulation (in the interests of small numbers of owners, investors, speculators and managers, rather than the majority of humanity) not only destroys nature in these pursuits, but also harms most of the world population. Not only failing to provide necessary resources for many among the population, but actively diverting these to markets for profit for those who claim ownership and control over those resources; or provides them only on a limited, precarious basis, in exchange for labor for capital (exploitation and accumulation).

This crisis has revealed that garbage collectors, grocery store employees, delivery drivers,and teachers are more essential to the functioning of society than investment bankers, CEOs and the cruise industry.

Jeff Shantz is a longtime union member, currently with Local 5 of the Federation of Post-Secondary Educators (FPSE, BC Federation of Labour). He is a founding organizer with Anti-Police Power Surrey, a grassroots community group in Surrey (Unceded Coast Salish territories). He teaches on corporate crime and community advocacy at Kwantlen Polytechnic University. His publications include Manufacturing Phobias: The Political Production of Fear in Theory and Practice (University of Toronto Press), and the Crisis and Resistance trilogy (Punctum Books).

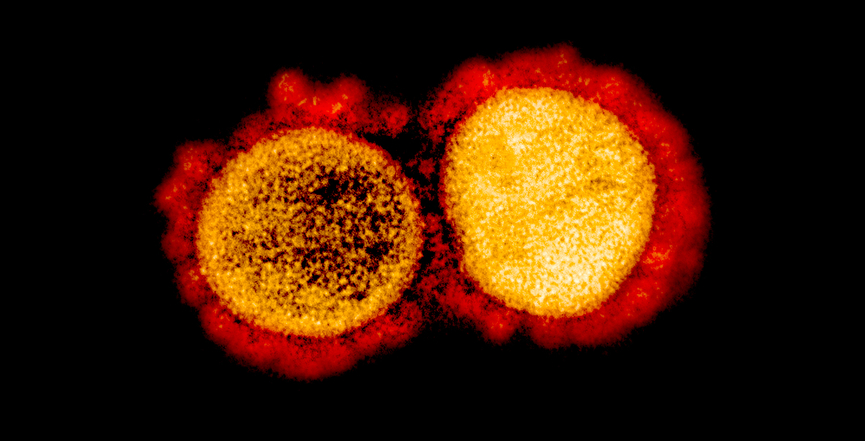

Image: NIAID/Flickr