Where do ex-politicians go when they retire? It would appear that they take up sinecure amongst the boards of directors at Canada’s leading telecom-media-Internet (TMI) companies.

The appointment of recently retired Industry Minister Jim Prentice to Bell Canada’s board of directors and Stockwell Day’s appointment to Telus, respectively, in the last two weeks has tongues wagging. Many think it ain’t right, others see no problems; I see it as business as usual, systemic and a big problem that contradicts the ideals of a free press and any notion that TMI policy in this country is anything more than industrial policy and a major industry-player protection racket.

Of course, not everyone sees things this way. As one lobbyist from the software industries in Canada badgered me over the weekend on Twitter, what’s an old political hack supposed to do when they leave office? What’s wrong with Prentice and Day taking up shop at Bell and Telus?

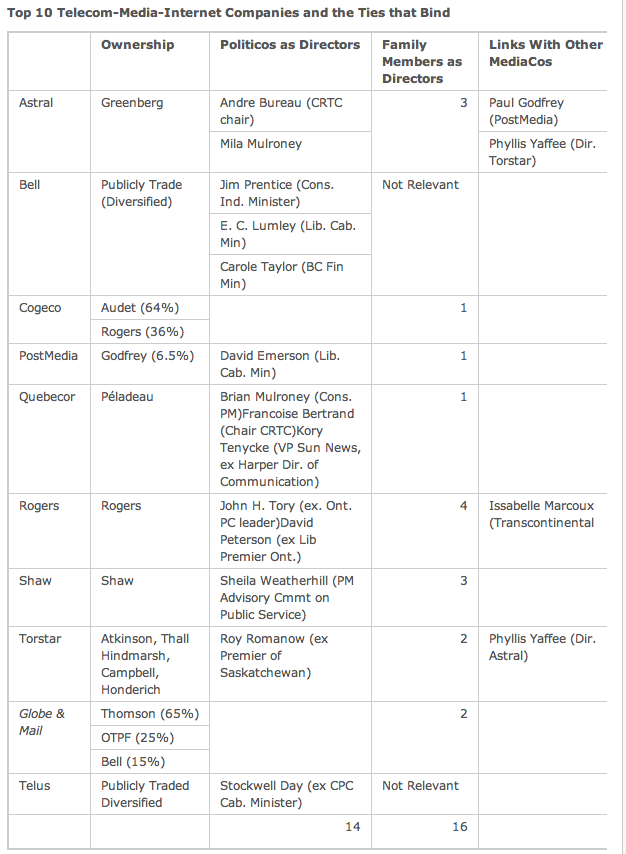

Well, lots. If it was just Prentice and Day stepping from the halls of Parliament to the panelled boardrooms of corporate Canada, perhaps it would be exceptional and not much to be worried about. However, if we look at the boards of directors at the top ten TMI players in Canada, we see that they are not the exception but the rule. The boardrooms are brimming with their type, with a total of fourteen directors — an ex-prime minister (Brian Mulroney at QMI), an ex-first lady (Mila Mulroney at Astral), two former chairpersons of the CRTC (Francois Bertrand at QMI and Andre Bureau at Astral, and more, as the chart above shows — occupying these coveted spots.

Sources: Corporate Annual Reports and Forbes Corporate Executives & Directors Search Directory <http://people.forbes.com/search>

Things are particularly strange in Canada by the added fact that eight of the top ten TMI companies in this country are family-controlled. This degree of media mogul control and political ties to the inner sanctums of top media companies is reminiscent of an “ancien capitalism,” where families and the “political class” are in charge rather than citizens and “expert” managers at the helm of publicly-traded firms where ownership is dispersed and corporate operations transparent.

Things are different in the U.S., where Eli Noam points out in his authoritative Media Ownership and Concentration in America that the number of owner-controlled media firms fell from 35 per cent to just 20 per cent between 1984 and 2005 (p. 6). I think that Noam slightly exaggerates the decline given that five of the top global media conglomerates — Comcast (the Roberts family), News Corp (Murdoch family), Viacom-CBC (Redstone family), Bertlesmann (remnants of Bertlesmann and Mohn families) and Thomson Reuters (Thompson family) — are of this type. Moreover, the media baron still cuts a large figure at the top ICT and Internet companies too; think: Apple (Jobs), Facebook (Zuckerberg), Google (Page, Brin and Schmitt), Microsoft (Gates and Ballmer), Yahoo! (Yang), IAC (Diller and Malone) and CBS (Redstone).

The ongoing case of the telephone hacker scandal in the U.K. reminds us that with the Murdock family — Rupert and his son James — at the helm, we are far from the end of the era when media moguls ran supreme. Thus, while not totally unusual, the degree of ties between moguls and political appointments at Canada is of a different kind and more extensive. Such arrangements are backwards, if you will, and more like nations with a tradition of oligarchic capitalism, as in Russia and Latin America, then in the liberal capitalist democracies of the U.S. and Europe.

It is not that we just have an outmoded system of family control with ex-politicos having positions of influence right across the ranks of TMI sectors, but also that the main players have ownership stakes in one another’s companies, as is the case with Rogers owning about a third of the equity in Cogeco and Bell a residual 15 per cent stake in the Globe and Mail.

Also blunting the sharp edge of competition and independence between different players in the market is the fact that directors on the board of one company sit on the boards of supposed rivals. Phyllis Yaffee, an industrial stalwart with oodles of experience and one who actually does have the expertise and savvy to fill a directors’ shoes is on boards at Astral and Torstar. Paul Godfrey, also an old hand and savvy operator in the business, sits on the boards at Astral and PostMedia Co. — a company whose development he has spearheaded to assume ownership of the twenty-odd newspapers (Ottawa Citizen, Windsor Star, National Post, Calgary Herald, Montreal Gazette, etc.) left behind by the wreckage of Canwest. That wrecked vessal is yet another company that was family controlled (the Aspers) and not shy about stacking its board with ex-politicos (e.g. Derek Burney, ex-chief of staff for Harper).

We also, as I have said repeatedly in this blog and elsewhere, have a very highly concentrated set of industries. Altogether, the big 10 firms listed in the table above account for just under three-quarters of all revenues in the TMI industries (excluding wired and wireless telephone services). I think the two are related.

It is not just that all our TMI industries, individually and as a whole, are very highly concentrated, but that policy and regulation in this country does not deal with this fact. Instead, policy-makers and regulators, to a large degree, cultivate concentration on the grounds that whatever problems this raises will be offset by industrial gains.

As David Ellis pointed out the other day, the CRTC does not regulate the TMI industries on the basis of any known standards of market concentration, but functions primarily to grease the supply-side of the industrial machinery that makes up the TMI sectors.

The problem is not just that this leaves consumers and citizens on the sidelines while industry calls the shots. The problem is that the phenomenon of politicos on the boards of directors at the major TMI companies, and the revolving door between the regulator and government policy shops on one side and industry on the other are pervasive, enduring and systemic.

What this means is that we cannot just look for one-off instances of influence peddling, as in, say, the allocation of spectrum in past and forthcoming wireless auctions, as Peter Nowak points out. Nor is that putting Harper’s former director of communication, Kory Tenyecke, in the position of VP at QMI’s Sun News will leave a dirty trail of finger prints on every story covered, with lurid tales of stories spiked and stories spun to favour Harper and the Conservatives.

To be sure, a few cases of such things will happen, with one or two leaking out to become grist for the mill and confirming some people’s worst fears. The problem is deeper than that, however, and less easy to suss out in terms of what it all means. However, as I showed during the election this year, it is true that of the 22 papers that issued endorsements for prime minister in the last election, all but one stood foursquare behind Harper — a wall of Conservative editorial opinion behind the Conservative candidate for PM.

Yet, the meddling hand of direct owner or political influence is much more subtle, and rarer than this. Instead it takes place at two more general levels: corporate policy-making and the allocation of resources; say, resources for faster Internet connections, more journalists and coverage of world affairs and the environment versus cut-backs, low levels of investment and fluffy content to titillate and instigate bickering rather than understanding and civil discourse. It is at this general level that directors hold sway. Indeed, that’s what they’re hired for: to set long-term policy and make sure that those directly controlling the purse-strings do so wisely.

Beyond this, the real problems are three-fold. First, the revolving door between the regulator (CRTC) and those who make the rules while in government, on the one hand, and the TMI companies, on the other, institutionalizes an approach to media policy as industrial policy and a strategic game. The extent of this also means that everybody in the game must adopt a similar strategy, which only aggravates the problem and makes things all the less apparent in terms of who and what is really calling the shots.

Consequently, regulation and policy-making is not so much about guiding the development of telecom, media and Internet in relation to democratic and free press values but industrial policy concerns. As I stated earlier, the CRTC serves principally to grease the supply-side machinery of these industries, rather than regulating in the public interest or in relation to a broad understanding of how people actually use media facilities and what we want. Perhaps this is not surprising, given that the last known sighting of the CRTC’s old motto, “communication in the public interest,” was in December 2008 (see here). It has disappeared from the top of its web page and prominent place on the front of publications ever since. No wonder some commissioners and the vice-chair have a hard time understanding the link between media and democracy.

Such arrangements are an affront to common sense and to principles of a free press in liberal capitalist democracies. They smell bad and smack of crony capitalism unfit by even the standards of liberal capitalist democracies.

Finally, they fly in the face of liberal theories of a free press. According to classical theories of the free press, and especially Whig tales of press history from the rise of advertising-funded mass media in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the media are supposed to be independent of government. They are also to serve as a watchdog nurturing the public sphere rather than as waiting lapdogs for retired politicos in the hope that they can tilt the industrial policy-making game in their new masters’ favour.

Dwayne Winseck is a professor at the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University. This content first appeared on Winseck’s Mediamorphis blog.