I spent most of my academic career documenting the lack of racial diversity in Canadian newsrooms, and studying the stereotypical and inaccurate coverage it often helped to produce, particularly when the news involved Muslims and Black and Indigenous peoples.

I politely called it “blind spots” or being “out of touch with your community.”

It was really something much worse — institutional or systemic racism.

As the world comes to grips with the very public murder of a Black man in Minneapolis by a white police officer, and as militarized police forces take to the streets to stifle the subsequent protests, questions are being asked about how equitable society’s major institutions are, and whether some — like the justice system — are infected by systemic racism.

No one has yet asked if we can rely on our news media to investigate it.

I say we may have a problem.

For anyone who wants to know what the face of systemic racism looks like, watch the YouTube video of Derek Chauvin pressing his knee down on the neck of a handcuffed George Floyd for more than eight minutes as bystanders plead with him to stop. The video shows Chauvin just staring at the camera with his hand casually on his hip as Floyd’s life drained away. He looks like he thought he could really get away with it.

For his part, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has acknowledged that systemic racism exists in Canada. He has called it out several times since Floyd’s killing, and late last week committed himself to “changing the systems that do not do right by too many Indigenous people and racialized Canadians.” He stopped short of saying how to do that.

Others, like columnist Rex Murphy and Quebec Premier François Legault, deny such a thing could exist in Canada.

While Legault acknowledged past incidences of discrimination in his province, he downplayed their severity, telling reporters, “We have this discussion very often. I think that there is discrimination in Quebec, but there is not systemic discrimination. There’s no system of discrimination, and it’s a very, very small minority of people doing this discrimination.”

Columnist Murphy, a 73-year-old white man known for his conservative views, was blunter: “We are in fact not a racist country.”

I couldn’t help linking Murphy’s myopic denial to what U.S. President Donald Trump said this week. He flatly denied that systemic problems exist in American police departments, declaring that 99.9 per cent of the nation’s officers are “great, great people.”

Recent polls indicate that Trump is out of step with many Americans on the protests. A Monmouth University poll released last week found that 76 per cent of Americans — including 71 per cent of white people — called racism and discrimination “a big problem” in the United States. According to the New York Times, “Never before in the history of modern polling has the country expressed such widespread agreement on racism’s pervasiveness in policing, and in society at large.”

Polls done recently show that anti-Black racism is very real in Canada, too. According to Michael Adams of the Environics Institute for Survey Research, “Black youth in Canada’s largest city are growing up being observed, questioned, dismissed and belittled by their fellow citizens because of their race, and are violently harassed by the very public institution we should turn to for protection.” In his poll, 80 per cent of young Black males in the Greater Toronto Area said they have been stopped in a public place by police.

The fact that pollsters are telling us this, and not the news media, is proof of a long overlooked problem.

There is plenty of evidence that reporters, editors and producers working for mainstream newspapers and broadcasting outlets in this country are institutionally incapable of covering race and racism in our society. Yes, there have been notable individual investigative journalism projects focusing on race, including the Toronto Star on police carding that singles out Black people, the Globe and Mail‘s series on murdered Aboriginal women, and documentation of a neo-Nazi paramilitary group’s recruiting methods by the Winnipeg Free Press. But everyday news coverage tells a different story.

Why is that important? “As a major institution in society, the media play a critical role,” says an article on the website of the Canadian Anti-Racism Network, a non-profit agency that keeps track of discrimination. “They provide us with definitions about who we are as a nation; they reinforce our values and norms; they give us concrete examples of what happens to those who transgress these norms; and most importantly, they perpetuate certain ways of seeing the world and peoples within that world.”

The article gives examples of the various ways the news media marginalize and stigmatize people who are not white. I invite all newsrooms to read it, and to measure their own behaviors against the elements of systemic racism it identifies.

I am not an expert on racism and, as a privileged white man, have never been a victim of it. I don’t know what it feels like. But I have chosen to use that privilege, and my experience as a senior newspaper editor and academic, to study what it looks like.

For one thing, those newsrooms are overwhelmingly white. I did the only demographic survey of people who work in Canadian newspaper newsrooms in 2004. My research showed that only 3.4 per cent of newsgatherers were non-white, at a time when Aboriginal people and people of colour constituted 16 per cent of the Canadian population. No update has been done in the 15 years since, possibly because the industry does not see lack of representation as a problem.

It is a problem. The easiest measure of whether news coverage keeps pace with the diversity of the community is to count who is used as an expert in media reports, especially who is interviewed in stories that affect everyone — like the economy, the weather, traffic, travel, education and health care.

I worked with Professor Wendy Cukier and her team at Ryerson University’s Diversity Institute to do just that in 2010. DiverseCity Counts showed that 23 per cent of people interviewed in such stories broadcast in one week by Toronto’s five major TV stations were non-white. That’s in a coverage area whose population is 49.5 per cent non-white. A local consumer story, “the search for the perfect prom dress,” featured shots exclusively of white teenage girls trying on dresses and being served by white store owners.

In the four major daily newspapers we monitored in the same week, no columnist who was a visible minority wrote any of the 43 columns published in sports sections, and only one of the 75 columns published in lifestyle sections.

My analysis of media coverage of two major news events that involved racialized people — the Ipperwash clash in 1995 when police shot and killed Dudley George, and the so-called Toronto 18 terrorist case of 2006 — showed reporters ignoring commonly understood journalistic standards of verification and fairness, and opinion columnists resorting to group guilt.

You would think, with the prime minister opening up a can of worms about systemic racism, newspaper editorial writers would be rushing to examine the evidence and either agreeing or disagreeing with his rhetoric. That has not happened, unless I’ve missed it.

Instead, the Toronto Sun sidestepped the message and tried to discredit the messenger. Its editorial called Trudeau a hypocrite and said he had lost the moral high ground on racism because he has “appeared so many times in blackface he’s not quite sure how often he’s done it.”

Agreeing we have a problem is only the first step. It’s far harder work to decide what to do about systemic racism. But surely we need to start.

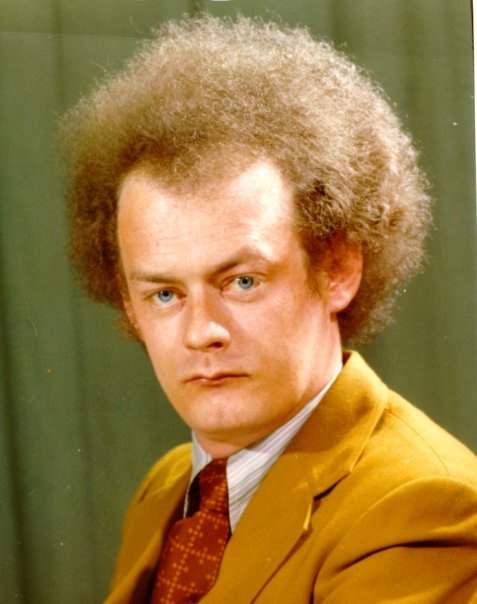

From media executive to media critic, John Miller has seen journalism from all sides (and he often doesn’t like what he sees). He draws on his 40 years in news, including five years as deputy managing editor of the Toronto Star, and 10 years as chairman of the School of Journalism at Ryerson University. His 1998 book Yesterday’s News documented how newspapers were forfeiting their role as our primary information source.