A Black immigrant in Toronto waves an everyday object in a “threatening” manner. Police are called. The man is described as disturbed, unruly, unstable, and, most importantly, dangerous. Concerned police plead with the man to drop the weapon, but their cries are ignored. Finally, they shoot him. He dies.

In 2015 the man was Andrew Loku, a refugee from South Sudan, killed holding a hammer. Police officers claim that Loku acted erratically and rushed them. His death was investigated by the SIU and the officers involved were cleared of any wrongdoing. His death was one of the incidents that led organizers to establish Black Lives Matter Toronto.

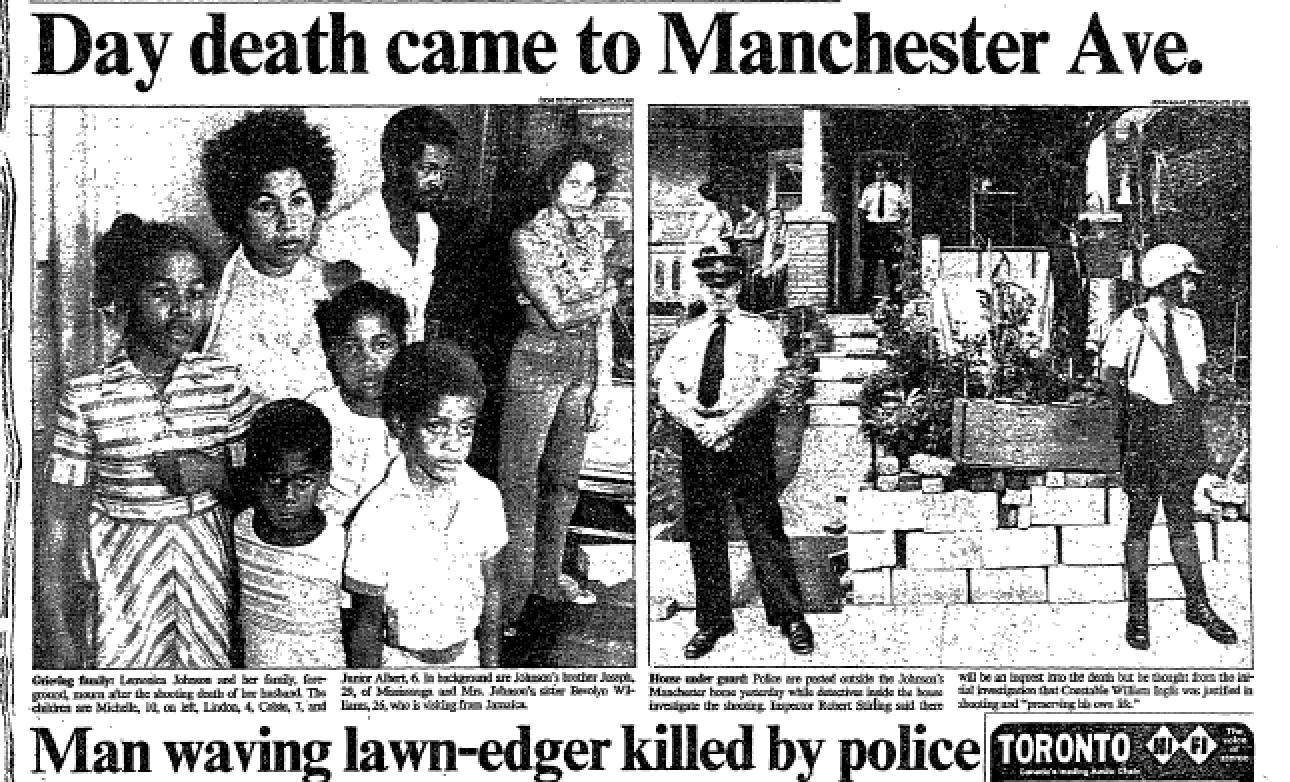

In 1979 the man was Albert Johnson, a Jamaican immigrant killed in his Manchester Ave home holding a lawn edger. Police officers claim that he bounded down a staircase towards them wielding what appeared to be an axe. Johnson’s death led to protests from the Black community, a high-publicity trial and the acquittal of the two accused officers. The trial of the two officers would eventually result in the establishment of the SIU.

Separated by nearly 40 years, both men were killed in almost identical circumstances at the hands of Toronto police. What is particularly chilling about both incidents is not merely the violence, nor the similarities of their deaths, but rather the virtually identical responses to both deaths in the Canadian media.

Killable Black bodies

The uncanny similarities between both men’s deaths offer two clear examples of a pattern that is usually too subtle to detect: when white police officers kill Black men, Canadians look to a range of excuses and justifications that shift the blame from the killer to the killed. In our media and in our collective responses, we engage in the same pattern time and time again.

In Johnson’s and Loku’s case, perceived mental health problems transform racist killings into unfortunate tragedies. This pattern has gone on for years: Reyal Jardine-Douglas (2010), shot by police on a TTC bus and Lester Donaldson (1998), shot in the hallway of his rooming house, were both described as “troubled” men with “mental health issues.” For Jermaine Carby (2014), his “mental health challenges,” “suicidal tendencies” and “well-documented history of mental instability” justified his death at the hands of Peel Police officers.

In the shooting death of Michael Eligon (2012), Toronto Star reporters began their story by noting that he “suffered from depressions and delusions.” Perhaps the most visceral description comes in the case of Abdirahman Abdi who was beaten to death by Ottawa police. Newspapers describe Abdi as not merely mentally disturbed, but as “frothing blood from his mouth.”

Where the mental health of the deceased can’t be used to justify their killing, reporters draw on victim’s alleged criminal past. Michael Wade Lawson (1988), shot in the back of the head by Peel Police officers, was described as a criminal and joyrider. In the case of Buddy Evans (1978), his criminal behavior and status as a “street brawler” justified his shooting. Albert Johnson had “numerous run-ins with the police.”

Similarly, when describing police encounters with Johnson, Carby, and Evans, Canadian media highlights how the officers involved were all “scared for their lives.” This rhetoric transforms the silenced, deceased victim into a violent aggressor while the police officer becomes the sympathetic figure, the border guard defending the public from this violent, criminal Black man.

What is staggering is not merely the repetition of familiar tropes and stereotypes by which a victim of police violence is transformed into a mentally unstable, dangerous, and ultimately killable subject. Even more horrific is the ease with which this history is repeatedly forgotten by Canadians such that each incident of police killing is imagined to be the first.

Justifying police killing a national past-time

Forgetting these names and ignoring these histories makes these killings possible. It is only by learning these histories that we can begin to understand this particularly Canadian strain of anti-Black racism.

The cases of Albert Johnson and Andrew Loku are particularly revealing in this sense both for their striking similarities and in the way that the mental health problems of the victim are used to justify racist police killing.

In the March 31, 2016 Toronto Star, president of the Toronto Police Association, Mike McCormack, insisted that the killing of Andrew Loku “is not about race” but rather describes the death as “the tragedy of Andrew Loku.” He insists that Loku’s Black skin “had no bearing on the officer’s decision that night” and “What we don’t need is people trying to distract from these real issues and making this tragedy about race.”

The real issues, according to McCormack, are Loku’s mental health and the need to arm police officers with tasers. As Anthony Morgan argues, “McCormack’s bald-faced claims that race had nothing to do with Mr. Loku’s death are…not only ridiculous, but also baseless.”

Morgan points out that mental health and racism are not exclusive and that a Black man with mental health issues may still be the victim of racist police violence. Therefore a victim’s mental health never justifies their death at the hands of police. He also uses the historical record to demonstrate that “The tragic truth is that this kind of policing has seemingly rendered it permissible for Toronto police to continually take Black life with impunity.”

If it’s good enough for the police, it’s good enough for the media

There are a number of striking parallels between McCormack’s arguments and those made about the death of Albert Johnson some 30 years earlier. Paul Walter, serving in the same role as McCormack when Johnson was killed, also ignores this history of police violence against Black men.

He insisted that Johnson “was sick” and the tragedy of his death was “that the system broke down for him long before the two officers broke down his door.” For Walter, it is Johnson’s mental illness and the failings of the system, rather than racist police, that killed Johnson. His comments were reported, verbatim, by Christie Blatchford in her coverage of what she calls “the Johnson trial” (the very name of which reveals whose character is really under scrutiny).

Blatchford’s reporting is particularly instructive as she consistently depicts Johnson as a mentally disturbed and dangerous man who terrified and threatened rational and peaceful police officers. She regularly describes Johnson as “mentally ill” and as exhibiting “increasingly erratic behavior.” Blatchford accepts the police account of Johnson as “berserk” and acting “in a rage.” She transcribes the police account of Johnson’s “bulging” eyes and “puffed” cheeks.”

Similarly, Don Dutton describes the scene entirely from the police perspective: “Blood was running from a cut on Albert Johnson’s face and he was swinging what looked like an axe as he came down the narrow stairs.” Johnson’s bloody face, the lawn edger that looked like an axe and the narrow stairs — each detail aligns the reporter’s narrative with that of the police.

Neither reporter weighs these claims against Johnson’s neighbours’ and relatives’ testimonies that he was calm and peaceful. Instead, they present the police testimony (which is inconsistent and was changed after conflicting with ballistics evidence) as fact.

Blatchford writes that “it’s true that just about everyone who came into contact with the 6-foot 200-pound Johnson in the last months of his life says…that he was mentally ill and needed help.” Never one to let the facts get in the way of a good opinion, Blatchford neglects to mention the testimony of Dr. Rodney Mahabir who interviewed Johnson one month before his death and concluded that Johnson suffered from no major mental illness.

Johnson met with Gail Guttentag, of the Ontario Human Rights Commission, to ask for help about the constant police harassment. Guttentag wrote that Johnson’s “biggest fear…was that police would shoot him down. He repeated that he thought the police are trying to kill him, and have been making a concerted effort to continually and increasingly harass him. He feared that this would culminate in his own death.” Ten days later, police killed Johnson in his own home.

“Unavoidable tragedies”

Albert Johnson’s death was “almost unavoidable.” Loku’s death is a “tragedy.” In these and other numerous cases, the solemn words of white, liberal concern are offered as an empty gesture of concern for the Black community. Indeed, it is only within the twisted logic of Canadian white supremacy that in both cases police officers can be described as “concerned for the safety and well-being” of the very citizens that they have killed.

The pattern of responses to these killings demonstrates that in Canada, Black lives simply do not matter. White Canada’s continual mock-surprise at anti-Black violence and eye rolling at the notion of Canadian white supremacy indicate how unwilling we are to address this problem.

The ease with which Johnson and Loku are depicted not as victims but as violent, irrational, uncontrollable citizens demonstrates the manner in which Black people in Canada remain ultimately killable.

When Black people are killed by the police, white Canada has a ready script of liberalism, multiculturalism, and Canadian fairness that serves to silence any discussion of race and racism. This script makes it possible for white Canadians to cling to the truism that in Canada, it never is about race.

For Black people, however, that script is a terrifying one of white supremacy and Black death, both of which are at the heart of their Canadian experience.

Paul Barrett is a lecturer in the Department of English and Cultural Studies at McMaster University where he researches Canadian Literature, digital humanities, and critical race theory. He is the author of Blackening Canada: Diaspora, Race, Multiculturalism.

Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.