This is the second blog in a series about how Canada has historcially served as a place of refuge during uncertain times in the U.S. Read the first installment here.

By the time the United Empire Loyalists (British subjects who rejected the 1776 Revolution) were settling in and founding family dynasties, another group started to arrive.

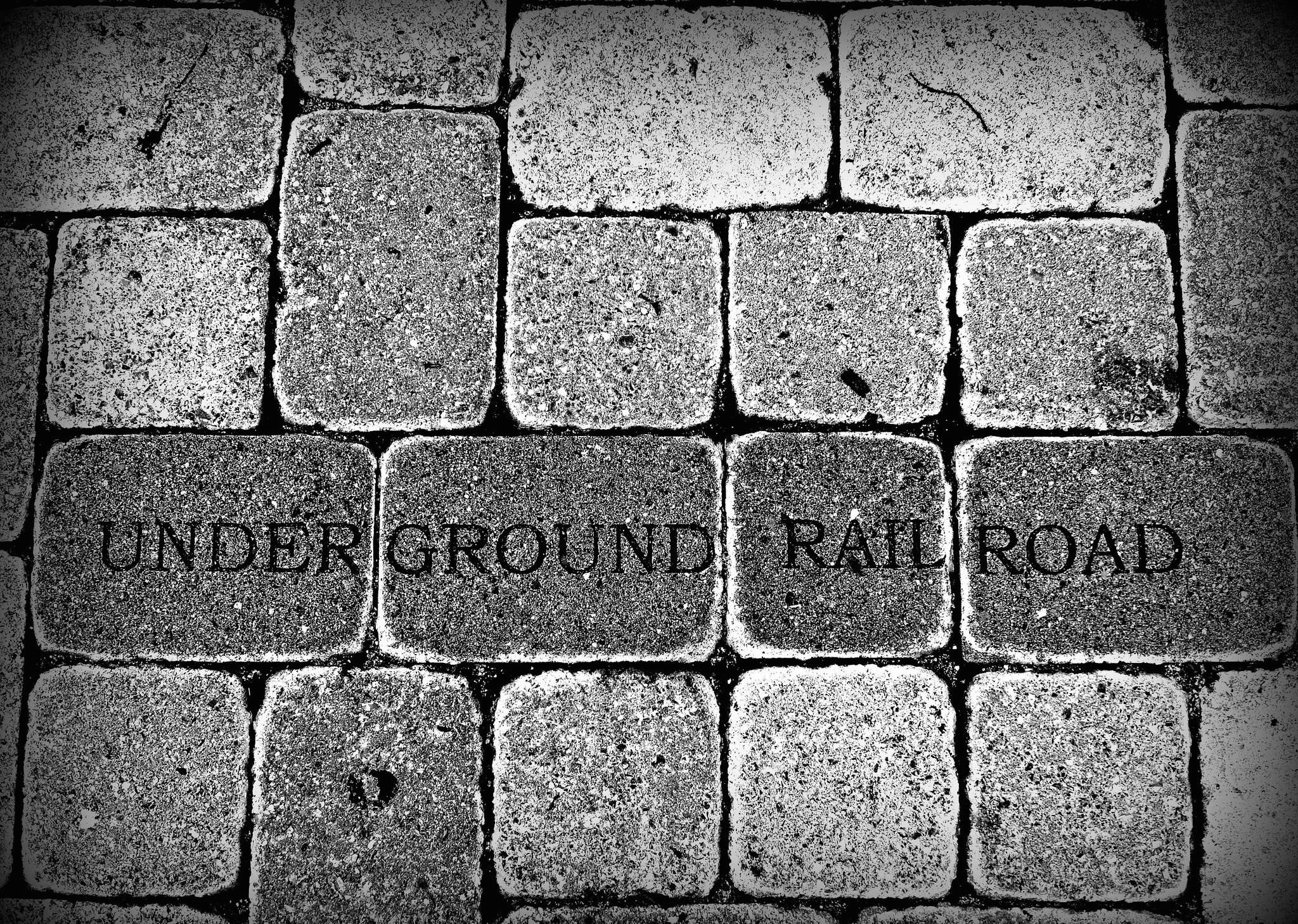

The Underground Railroad began in the 1780s and peaked between 1840-60, helping escaped slaves reach safety in (mostly) slavery-free Canada. Volunteers on both sides arranged safe houses and co-ordinated passage across the U.S.-Canada border.

Since Southern states had laws against teaching slaves to read or write — or giving them shoes — Blacks used work songs to spread instructions about how to travel north. For example, “Follow the Drinking Gourd” urges runaways to find and follow the North Star. The “drinking gourd” is the Big Dipper.

“It is impossible to know for certain how many slaves found freedom by way of the railroad, but it may have been as many as 30 000,” says Black History Canada. “The railroad’s traffic reached its peak between 1840 and 1860, especially after the U.S. passed its Fugitive Slave Act in 1850.

“The new law allowed slave hunters to pursue and capture enslaved persons in places where they would legally be free. It resulted in several attempts to kidnap escapees in Canada and return them to former owners in the Southern States.”

Other Black people had already lived in Canada before the Loyalists. Mathieu Da Costa was the first named Black person to arrive in Canada, in 1605, as a free man and a translator for Samuel de Champlain.

Thousands of Blacks took part as troopers in the War of 1812, to prevent a U.S. victory that might lead to a return to slavery. The British promised them freedom, and land, says Black History Canada. Black soldiers served nobly during the war, and spread the word among their kin that they received kind treatment in Canada.

In 1819, Lower Canada’s Attorney General John Beverley Robinson stated openly that residence in “Canada” made Blacks free and Upper Canada began offering land grants to black veterans.

In 1851, Toronto was the site of the first North American Convention of Colored Freemen, which formed the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada. The BHC website says that, “Hundreds of Blacks from all over Canada, the northern United States and England attended, where speakers included H.C. Bibb, Josiah Henson and J.T. Fisher.”

In 1853, Mary Shadd and her brother Isaac fled Virginia for Windsor and began publishing the first abolitionist newspaper, The Provincial Freeman. This made Mary Shadd the first publisher of colour in North America. In 1866, Mifflin Gibbs won a seat on the Victoria Town Council, becoming the first Black elected politician in Canada.

But in 1911, Alberta’s Frank Oliver wanted tighter controls on immigration. “He became the Liberal government’s Minister of the Interior in 1905,” says the government of Canada immigration policy timeline.

“Oliver was staunchly British, and his policies favoured nationality over occupation. By 1911, he was able to assert that his immigration policy was more ‘restrictive, exclusive and selective’ than his predecessor’s.”

The racist spirit of Frank Oliver’s law was not dismantled until 1962, when Prime Minister John Diefenbaker asked Ellen Fairclough (the first woman federal Cabinet Minister) to clean up the Immigration Act and the department too.

********

While escaped slaves were seeking their place in Canada, another band of fugitives arrived in conflict with Americans. The great Sioux Chief Sitting Bull and his followers fled to Canada, fresh from their June 1876 massacre of American Lieutenant — Colonel George Custer and 262 of his men.

Protecting land that was ceded to the Sioux in the Treaty of 1868, Sitting Bull led an aggressive response to the hundreds of prospectors and settlers lured by the Black Hills Gold Rush. After the Battle at Little Big Horn, the full might of the U.S. military penned in the warriors, demanding humiliating surrender and displacement to reservations.

Instead, Sioux fighters and family began slipping over the border to Wood Mountain, Saskatchewan, then part of the NWT. They numbered about 5,000 by the time Sitting Bull joined them in the spring.

According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, North-West Mounted Police Inspector James Morrow Walsh met with the Chief and established cordial relations, but was not able to convince Ottawa to provide the band with either food or a land reserve.

Starved out, the Sioux eventually slipped back to U.S. reservations. Chief Sitting Bull returned to the U.S. in 1881 and settled in Standing Rock reservation, before signing on to tour with Wild Bill’s Wild West Show.

******

Meanwhile, the Canadian West was about to feel settler pressure. The 1872 Dominion Lands Act kicked off an aggressive campaign recruiting immigrants to help colonize and farm the West.

Canada offered 160 free acres per adult male settler, provided that they lived on the land three years, built a permanent structure there, and cultivated 30 acres. Interior Minister Clifford Sifton widened recruiting to include all of Europe as well as England, and all of America.

According to another Customs & Immigration website, “the Department of the Interior under Sifton’s direction expanded its network of American offices and agents and mounted a strong campaign to attract experienced American farmers with capital.

“Estimates indicate that between 1901 and 1914, over 750,000 immigrants entered Canada from the United States. While many were returning Canadians, about one-third were newcomers of European extraction — Germans, Hungarians, Norwegians, Swedes, and Icelanders–who had originally settled in the American West.”

Americans tended to settle in Alberta and Saskatchewan, creating special ties that still affect provincial politics occasionally. There was, however, “no welcome mat” for Black American farmers.

“No attempt was made to recruit Black agriculturalists, for they were widely regarded as being cursed with the burden of their African ancestry. As unwelcome as Black settlers were, no law was passed to exclude them, although administrators devised careful procedures to ensure that most applications submitted by black people were rejected.”

Although Black people lived in Nova Scotia and parts of Ontario, few settled on the Prairies, which, except of course for the original Indigenous inhabitants, remained determinedly white. When a group of Black farmers from Oklahoma explored the possibility of living in Alberta, there were threats of violence. The Edmonton Municipal Council petitioned the federal government to bar Black people from immigrating.

These grave injustices seem hard to believe, now that Alberta has started to look like the rest of the world. Indeed, Canada’s immigration policies have swung between humanitarian impulses and hunger for more workers on one hand, and xenophobia on the other, as we shall see next time.

To be continued.

Image: Flickr/thadz

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.