Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Since the June release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s preliminary report on the history of residential schools, there has been heightened talk about how non-Indigenous Canadians can become better neighbours to those who are Indigenous. Now, a ruling issued by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) on January 26 provides yet another illustration of the shared road ahead.

The CHRT was responding to the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, which — along with the Assembly of First Nations — initiated a complaint in 2007. Although the process was long and arduous, the tribunal eventually ruled that Ottawa’s funding formulas provide between 22 and 34 per cent less to child welfare services for First Nations people. That’s compared to what provincial governments pay for similar services provided to other children. It’s a discriminatory practice that has gone on for as long as anyone can remember.

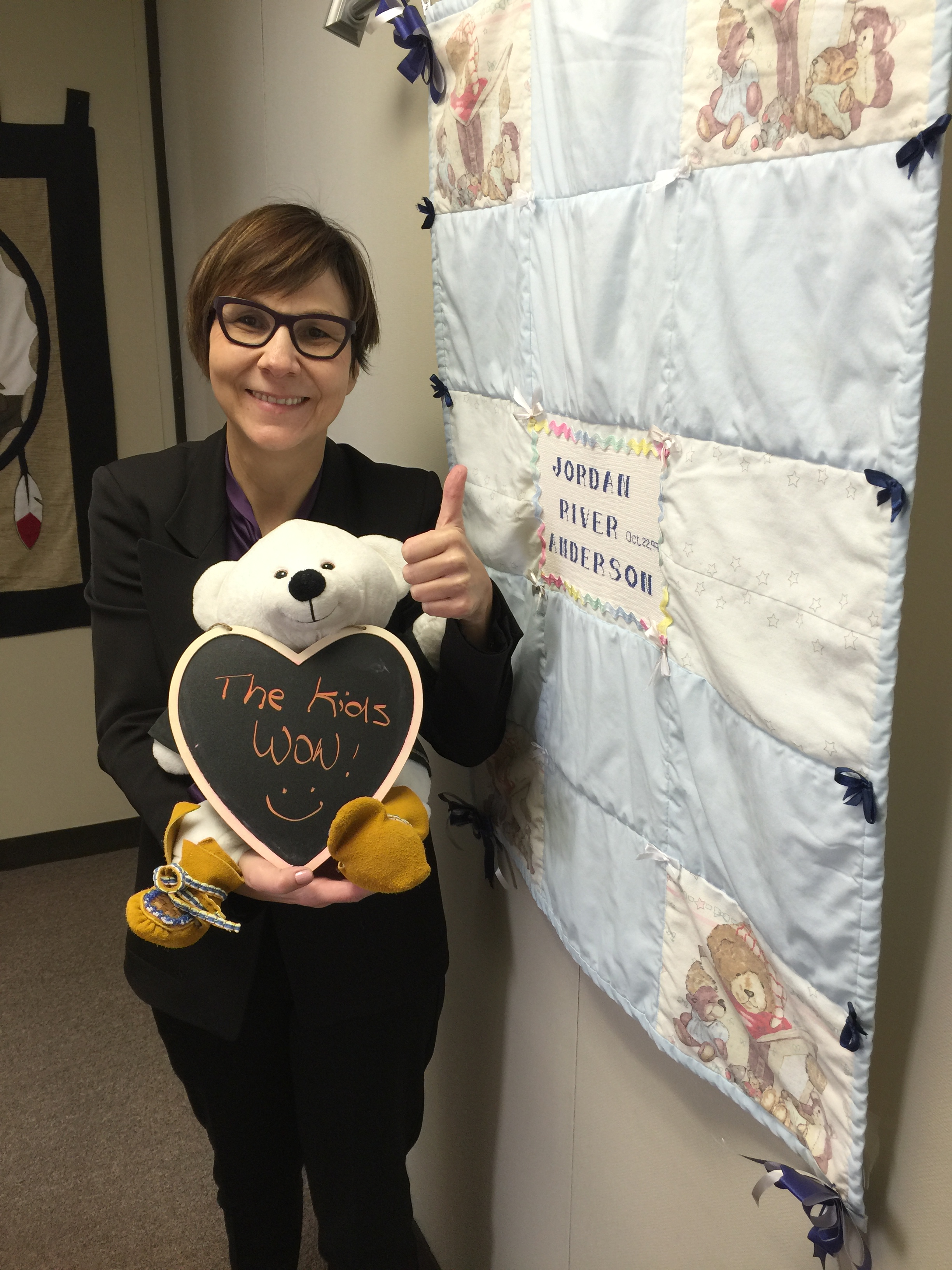

Cindy Blackstock

Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the Child and Family Caring Society, has been the most prominent advocate in the case. Blackstock says that the discrimination means services are fewer — and often of lesser quality — on reserves. And there’s another consequence of discriminatory funding models: it creates an incentive to place children in foster care because their communities and families have fewer resources to provide needed services for them.

As a result, says Blackstock, there are more First Nations children in foster care today than there were at the height of the residential school era. As Globe and Mail columnist André Picard correctly writes, “[This] is a continuation of racist (and in some cases genocidal) policies like the Indian Act, residential schools and the Sixties Scoop.”

Blackstock estimates that the Harper government spent more than $5 million fighting the technicalities of her group’s allegations before the tribunal. But it didn’t stop there. Government employees were ordered to collect personal information about her and spy on her. In response, Blackstock submitted a complaint to Canada’s privacy commissioner, who concluded that, indeed, her privacy had been invaded. She then launched a second complaint concerning the harassment by government officials. In 2015, the Aboriginal Affairs department was ordered to pay her $20,000 for the pain and suffering that they caused her. Blackstock gave the money to children’s charities.

Good neighbours can help

Regarding the funding of child welfare services, the CHRT has the power to order Ottawa to end its discriminatory practices. But it has not yet done so. Meanwhile, the initial response to the ruling from Liberal cabinet ministers has been positive. Ministers Carolyn Bennett and Jody Wilson-Raybould welcomed the tribunal’s decision and promised to work, collaboratively, toward solutions. “This government agrees that we can and must do better,” they said.

During the federal election campaign last fall, the Liberals promised to work with First Nations to tackle their many challenges. They also promised to implement all 94 recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Despite these expressions of goodwill, however, politicians will likely do only what Canadians will support — and that’s where good neighbours can help.

This article was published as a blog with the United Church Observer on January, 28, 2016.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.