Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

We sometimes take for granted, just how easy it is for well-meaning people to work in silos.

But, by the same token, we must also appreciate that sometimes movements must take time to find their voice, to understand their motivations and to articulate their demands.

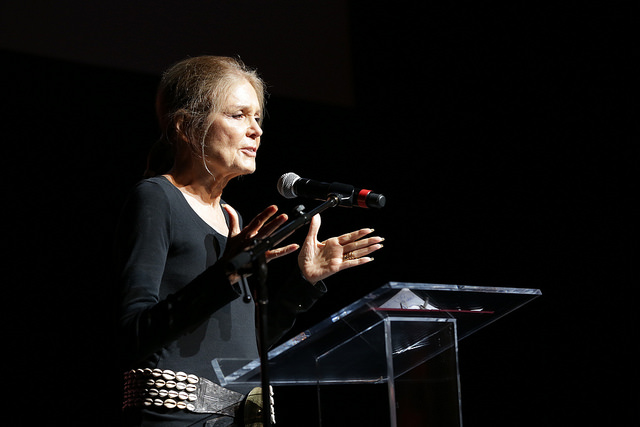

Gloria Steinem’s opening keynote speech at the Broadbent Institute’s 2016 Progress Summit challenged many of those in the room who are recognizing the intersectionality of their causes, but not always sure how to unite, and when.

“We are linked, not ranked,” says Steinem

“We grew up with the women’s movement, the environmental movement, the civil rights movement, the gay and lesbian movement,” pointed out Steinem to a packed conference hall in a downtown Ottawa hotel. “… it is important that each movement rises up in their own way.”

However, “at a certain time, we have to know that we are all interconnected.”

No one would doubt that at a time where growing numbers of young people from all backgrounds and experiences are converging to demand their rights — for police accountability, for Indigenous rights, for climate justice, for equity.

Indeed, long-time feminist journalist Michele Landsberg later pointed out that the #Ibelievesurvivors protesters at Toronto’s courthouse quickly joined the Black Lives Matter protest outside of Toronto Police headquarters, where she said one could also smell sweetgrass burning.

For too long, though, that interconnection wasn’t always named, points out Steinem, who credits her feminist activism to learning from Black women in the United States.

“It has never been possible to be a feminist, without being an anti-racist,” she explained, discarding the notion that the feminist movement was one representing white, middle-class women.

And while it’s critical that activists “must name ourselves, that we make ourselves visible, that we need to name our issues,” we’ve also got to recognize that the European concept of hierarchy brought to Canada and to the United States was alien to these lands and has remained a “curse.”

“That had we looked at what was here before us, we would have found a circle. That the paradigm of life is not a hierarchy, but a circle.

“We are linked, not ranked,” argued Steinem, before a boisterous chat with writer and activist Desmond Cole, that included a shout out to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Steinem acknowledged the three young Black women who founded BLM, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi. She shared with the audience their three principles of organizing:

1. Lead with love

2. Low ego, high impact

3. Move at the speed of trust

Racism in U.S. politics

Cole expressed his admiration for Steinem’s work and asked her a series of questions, including why there seemed to be a reluctance for U.S. Democratic candidates Bernie Sanders and Hilary Clinton to call out Donald Trump as a “racist.”

Steinem had no such hesitation. “Well, I’m not running so I’m happy to say he’s a racist,” she told the crowd with a smile.

While American politics — and Trump — weren’t far from the conversation, other common issues including pay equity, violence against women — what Steinem called “supremacist crimes” — and the need to help young men find their true selves and to be wary of the potential for messages about masculinity to dehumanize.

Steinem also addressed the reality of elitism pervading some social and progressive movements, and pointed out that elitism is “boring.”

“The world is divided into two kinds of people: those who divide the world into two kinds of people and those who don’t,” she concluded to applause and laughter.

Islamophobia in Canadian society

It was the world seen through paradoxical lenses that much of the following panel “Xenophobia & the Future of Canadian Pluralism” explored.

Author and commentator Jeet Heer set the stage for the discussion, taking the audience back to an uncomfortable time where political leaders in Canada deliberately used fear and ignorance to stoke suspicion of Canadian Muslims to win votes.

Interestingly, Heer laid the blame for the rise in Islamophobia not on 9/11 or geo-political issues, but specifically at the feet of the Republican Party and the attempt to question President Barack Obama’s legitimacy, referencing the work of Princeton associate professor Christopher Bail in his book Pointing to the book, Terrified: How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream.

Heer drew parallels between the tensions within conservative circles in the U.S. and in Canada on how to address changing demographics. On the one hand, embrace it, or, on the other hand, otherize and scapegoat. The latter clearly failed to work in Canada, and we’re seeing the struggle playing out currently in the United States.

For writer and activist Monia Mazigh, the attempts at scapegoating Muslim women in particular failed miserably, because former Prime Minister Stephen Harper cloaked his attack on Zunera Ishaq — the women who wanted to wear a face veil in a citizenship ceremony — in the language of feminism.

“But of course, we knew he wasn’t a real feminist,” said Mazigh, pointing to the Conservative Party’s deep cuts for women’s programs and myriad of other positions.

Not only were the claims of saving women superficial, but they actually led to attacks on Muslim women, added Haroun Bouazzi of AMAL-Quebec, who pointed to a spike in hate crimes against visibly Muslim women as a sign that such narratives were anything but feminist.

Coming together at the right moments

However, the struggle now against Islamophobia, argued Bouazzi is a further example of the need for progressive movements to work in concert — and to unite rather than to operate independently.

“We have to help each other struggle; these are the same struggles,” he argued. Both Bouazzi and Heer lamented the failure of the progressive movement to address issues of classism, as well as to implement meaningful policies of inclusion instead of being satisfied with what Heer referred to as “tokenism.”

“We do need to rethink the story of Canada,” argued Heer. “Not just the story of the dominant group, but all of the people who participated in creating this country,” added Mazigh.

And, one could argue, even if we have to work in silos at times, let the work be acknowledged and shared so that we learn to come together at the right moments.

Amira Elghawaby is a contributing editor at rabble. Follow her on twitter @AmiraElghawaby

Photo: flickr/ UN Women