Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

When I think of Bangladesh, the disaster at Rana Plaza is the first thing that comes to mind. On April 24 2013, a factory building on the outskirts of Dhaka collapsed, killing over 1,100 workers and injuring over 2,500 more.

Canadians were appalled to find that familiar brands such as Joe Fresh, an off-shoot of Loblaws, had been sourcing from a factory building where conditions were so bad that workers said they had been beaten to go back to work after cracks had been seen appearing in the walls and ceiling.

Canadian consumers — and consumers of cheap Ready Made Garments (RMG) all over the global north — have had to face that workers in faraway Bangladesh were paying the price for our collective appetite for cheap clothing.

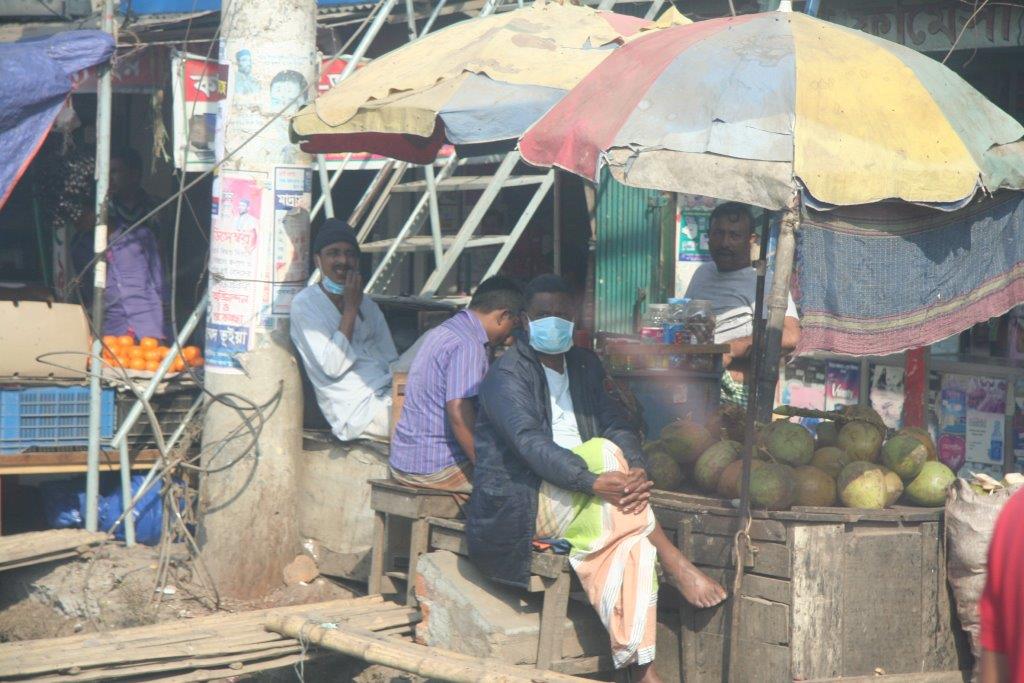

As part of a recent trade union delegation from CUPE, PSAC, USW, Unifor and the CLC to visit Bangladesh, a number of us Canadian trade unionists were able to see the chaos of this densely populated city for ourselves as we met with workers and activists from the RMG sector.

Unimaginable chaos surrounds Rana Plaza

Rana Plaza is not the first major industrial accident that has occurred in the RMG industry in Bangladesh. Less than a year earlier, there was a major fire at Tazreen Fashions on November 24 2012, which killed over 100 workers and injured hundreds more.

Somewhere between 4.2 and 4.5 million workers are employed by the RMG industry in Bangladesh. The country is small but densely populated: 156 million people live in an area that is less than half the size of Ontario (population 14 million). Of these 156 million, the vast majority live in and around the city of Dhaka, whose densely packed suburbs are also home to many of the 5,000+ RMG factories in the country.

Dhaka is one of the most densely populated cities on this planet — almost 15 million people work and live in the city and its suburbs with minimal public transit, and with little in the way of services such as electricity, water, gas or sewage. Add a couple of thousands factories and the result is a kind of chaos that is unimaginable to most of us.

These factories are housed in buildings that range from 1950s-built small spaces in the downtown core that employ 500-1,000 workers to huge purpose built compounds where 20,000 workers are employed.

The only quiet spot that we saw in Dhaka was the Rana Plaza site, which now sits vacant and accusing, while legal battles rage around its ownership and future disposition.

Horrific conditions for RMG workers

Hosted by the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity, we had the opportunity to meet with workers, organizers and activists to hear firsthand about the conditions under which they work and live.

Most of the people who work in the factories make less than $75USD a month. The minimum wage for the RMG sector in Bangladesh is now around $65USD a month. This can barely feed a family of three for a month.

Most of the millions of people working in this sector are young women, who leave rural Bangladesh in search of work. Once they find themselves in the city, work in the RMG industry is often the only option for many young women. They get themselves hired on by appearing at factory gates and asking for work.

Most often, they start as unpaid apprentices or sometimes as “helpers” who make far less than even the measly mandated minimum wage. Even after they graduate from such “training” positions, many workers are forced to work unpaid “overtime” in order to make the $65USD.

For this wage, even today, people are sometimes locked into factories for 8-12 hours a day — as was the case at Tazreen Fashions, where this prevented people from being able to leave the building after it caught on fire.

What happened at Rana Plaza and what happened at Tazreen Fashion are not isolated tragedies. Workers in Bangladesh have long been considered expendable, going back to the days when the land was part of the British Empire.

Famously, under British rule, Bangladesh, which was part of the “Bengal Presidency” experienced massive famines in the 1770s and then again during the Second World War — famines that led to the deaths of millions of working class people.

In many respects, Bangladeshi workers are still treated as expendable as they were treated by the British.

Support and solidarity is needed, not a boycott

Today, the rights of RMG sector workers to organize into unions is not respected by employers. People aren’t living under imperialism anymore, but they are certainly living at the mercy of global clothing chains.

Transnational brands that range from Joe Fresh and H&M to Adidas and The Children’s Place have been paying some attention to the structural safety of the factories from which they source the cheap disposable clothing, but do nothing to promote decent work or workers’ rights beyond the bare minimum of structurally safety for the factories.

While there are huge problems with the patronizing attitude demonstrated by Bangladeshi factory owners toward their workers, the ultimate balance of power lies not in their hands but with the brands who source RMGs from their factories and with consumers who buy these products.

As progressives, we need to consider our approach — Bangladeshi workers and activists were clear with us that they do not want boycotts of the industry. What they want is support and solidarity for their organizing.

We should mourn those who died and have sympathy for those who are still suffering, we should not forget that mourning and sympathy are not enough.

We need to offer our concrete solidarity to those who are fighting to ensure that the RMG factory workers in Bangladesh have safe working conditions, decent wages and benefits and access to the services they need to live their lives with dignity. Their fight is part of a global struggle against capitalism that Canadian workers are also a part of: they are just on the front lines of it in way that we are not.

Our solidarity cannot just be the small organizing projects that Canadian unions can support in Bangladesh: that is merely one aspect of our solidarity. Such solidarity projects helps organizations like the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity, which operate on shoe strings, and yet have incredible reach and impact.

But there is also a need for us to stay engaged, to engage the Canadian and Bangladeshi governments around trade policy in ways that help Bangladeshi workers and that we continue to monitor the developments in building safety and workers’ rights.

Transnational brands that sell RMGs in Canada need to know that we care not just about building safety but also about the human rights of workers. Our trade policy needs to reflect this.

Four years after the Tazreen fire and approaching the third anniversary of the collapse of Rana Plaza, it is now more important than ever to let the brands, the factory owners and the Canadian and Bangladeshi government know that we are watching.

Archana Rampure works at CUPE National and was part of the trade union delegation from CUPE, PSAC, USW, Unifor and the CLC to Bangladesh. Follow her on twitter @ArchanaARampure

Photos: Archana Rampure