Two days after 18-year old Mike Brown was shot eight times by a Ferguson County police officer, comedic actor Robin Williams hanged himself. As a relatively middle-class white person of a certain vintage, I saw my social media feed shift from displaying the odd note about the latest mainstream example that we live in a racist, white supremacist police state (a fact visible at all times to low-income people, persons of colour and colonized peoples) to all Williams, all the time. Even Barack Obama issued a statement a matter of hours after Williams died and didn’t release anything about Brown until three days after his murder.

Depression is a terrible thing to die from and even worse to live with. But the public response to these deaths represent a common trope in mainstream discourse that arises whenever we are confronted with the unsettling reality that our way of life is underwritten by a narrative of oppression, injustice and blood: it’s probably best, they insist, if we forget all about it.

Robin Williams, who once unproblematically played a character whose dead (white) daughter appears to him in the form of a Japanese stewardess because of an erotic fantasy he once mentioned offhand to her, suffered from depression and substance addiction — two points that uphold the tragedy of his narrative.

We don’t know much about Mike Brown, but we do know young black men in America have higher incidences of depression relating to trauma than any other demographic. We know that suicides account for more deaths in St. Louis County than homicides and motor vehicle rates combined. We also know that the mere fact of blackness has prescribed modes of feeling thrust upon its bearers: you are angry, you are unpredictable, you are dangerous, you are black. Mike Brown doesn’t need to have experienced any of these realities first hand, but we know they made up his daily life in Ferguson, Missouri. But some depressions count more than others.

The rash of Williams-related tributes that continue to flood Facebook and Twitter resembled a collective gasp of relief for white North America, despite their doubtless sincerity, offering a worthy distraction from the horror of Mike Brown’s murder and the state’s full military response to a community’s anger. Images of Williams laughing or smiling emphasized the meaningfulness of his passing — despite the fact that he was a depressive who spent four decades in front of a camera plying his craft of faking exactly that. A Vancouver morning radio show assured distraught fans that they could comfort themselves this Christmas when Williams’ last film will be released: A Night in the Museum 3. As if we needed any more explanation as to why wealth, fame and prestige might not be enough to finally achieve The Good Life.

But somehow, Mike Brown’s story grew. It grew partly because of the preposterous images of St. Louis County police officers in what has been described as military gear but would be more at home in a dystopic science-fiction film like The Hunger Games or Children of Men. Again, much of the discourse has taken a “making sense” tack: why did the police officer (now revealed to be Darren Wilson) feel compelled to shoot Brown? how can authorities bring order to Ferguson? what will finally placate the demands of the protestors? Residents of Ferguson and their allies who have been demonstrating for a week now don’t need answers to these questions because they know them in their bones: Brown was murdered by an instrument of legitimated state violence bent on keeping a racialized population poor and subdued. And they’re sick of it.

This “but what happened?” approach is a time-tested method for deflating resistance. Think of lengthy, drawn-out performances of public consultation where power’s preferred outcome is approved anyway: be it pipelines, logging or prostitution. But suppression disguised as a rational, “moderate” drive for empirical truth hasn’t worked so far because the proof, the raw alacrity of centuries of institutionalized racism congealed in the spectacle of tear gas, curfews and laser-sighted assault rifles on ordinary people refutes moderation like Johnson’s foot striking a rock.

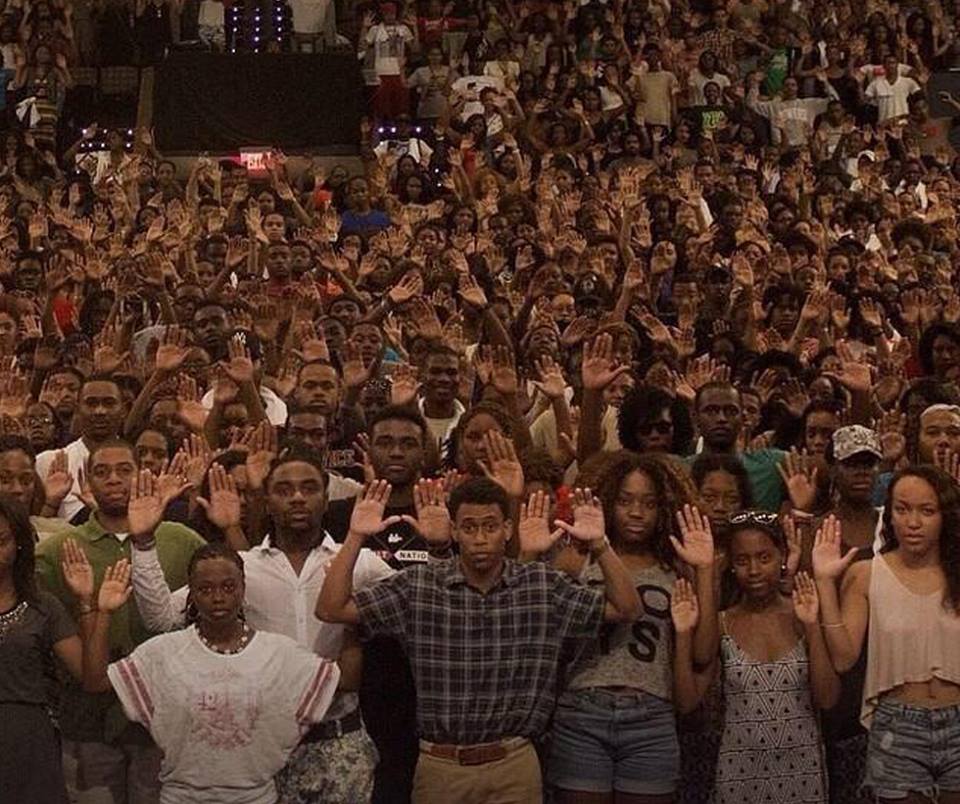

The now-iconic, brilliant image of “Hands up, don’t shoot” haunts the media landscape in between the usual slanted reports of “rioting” and “looting.” I am reminded of Ossie Michelin’s striking portrait of Elsipogtog resident Amanda Polshies, who held up a single eagle feather in defiance of the RCMP who had been called in to her community to defend the interest of a fossil fuel corporation. These images, like Michelin’s, are indigestible if you benefit, like I do, from white privilege. If we puncture the fantasy that assures us the police are here for our protection (save a few bad apples), that the legacies of slavery and colonialism are not my own and that our nations’ prisons (and morgues) are full of people who deserve (at least a little) what they got — and surely these images puncture it — we can’t easily mend it.

But we can try. And the work of publicly mourning Robin Williams’s death went a little ways toward that end. There are others: I’ve been struck, as usual, but the satirical pieces that are using Brown’s murder as grist for their clickbait mills. The Onion offers “Tips For Being An Unarmed Black Teen.” “8 More Unarmed Teens Still At Large,” says Clickbait, The Onion‘s satirical satire site. Buzzfeed has been archiving shocking images of our military society for our titillation and the satisfaction of muted rage.

But articles like this, designed to entertain rather than edify, don’t illuminate the coercive power of state violence and systemic oppressions. They don’t tease out the many shades and tenors of oppressions the way a diverse number of expression modes — news, analysis, satire, photography — might. Instead, the utterances and images that make us white folk uncomfortable — the shocking spectacle of state violence literally occupying a neighbourhood of domestic citizens — become defused through a genre more comforting, far more, it should be said, white: Daily Show-esque satire where the content is no longer the violence of power but a vague absurdity that could be racism as easily as it could be a dog eating underwater.

I’ve posted tributes to dead celebrities before — I liked a photo of Lauren Bacall marching with communists the day after Williams died. I’m not calling for a moratorium (although maybe we could just try it out for awhile and see what happens?). But we should recognize that in our media some depression matters more than others, some tragedies more visible, some pains felt more acutely — often in unjust ways that uphold rather than disassemble systems of oppression. And it is that moment, when we feel a lived discomfort forcing its way into our privilege safehouse, that we should fight the instinct to defuse it by giving in to the warm embrace of pop culture.

(Satire has a place in these moments, by the way. The Onion produced one such example last week: “Sometimes Unfortunate Things Happen In The Heat Of A 400-Year-Old Legacy Of Racism.” The piece works because it turns the received narrative on its head and exposes the work the usual police clichés do to uphold oppressive power structures: “When emotions run high, it just takes two seconds following dozens of generations of systemic social, economic, and political discrimination toward non-whites — particularly African-Americans — for things to get way out of hand.”)

The question is often asked of incidents like Mike Brown’s murder (because they are legion) what can we (white folk) do? First, we can refuse to participate in discourses that seek to minimize or deflect from what is happening in St. Louis County. When someone mentions looting, you correct them. When someone speaks of rioting, you tell them they are mistaken. When a celebrity you admire passes, take a moment, but don’t allow the media to manipulate you.

Second, and this is probably the more important thing, recognize that there are Mike Browns that are still alive. In Canada, they are more likely to be Aboriginal than African American. Acknowledge that there are many Fergusons, occupied by state power in sometimes invisible but always suppressive ways. The insidious thing about the neoliberal state is that its instruments only appear when they are needed. We don’t have tanks patrolling the streets — until state and corporate power is threatened. Make those moments — from Elsipogtog to the G20 in Toronto — unacceptable in this country and they will be less acceptable in Ferguson.

Image: Megan Sims (Twitter: @The_Blackness48)