As much of Canada starts to emerge from COVID-19, Indigenous communities along the James Bay coast in northern Ontario are feeling it worse than ever.

Just as the rest of us are toasting victory, those communities are in a dire state of medical emergency. In Kashechewan, 12 per cent of the population are afflicted with COVID-19; the majority of those infected are children.

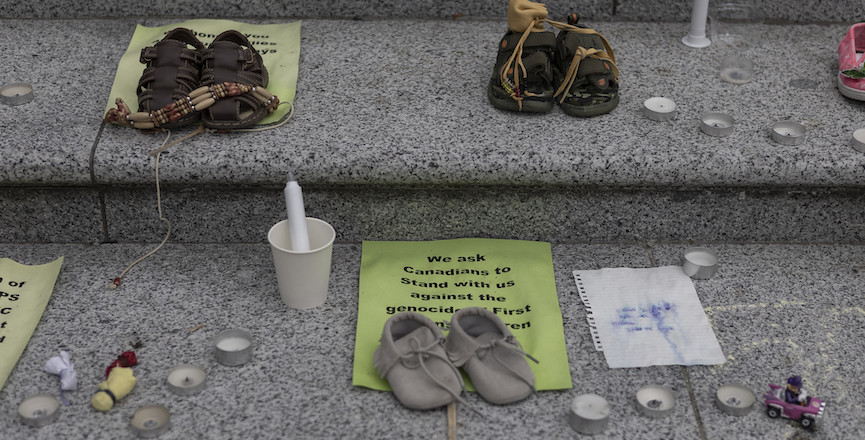

At the same time, we are learning about more unidentified children’s bodies on the grounds of former Indian residential schools. Recently, researchers have found 104 unidentified children’s graves at the former residential school in Brandon, Manitoba.

Despite federal political leaders’ public tears and pious statements of sympathy, the Canadian government is still going to court to fight First Nations children who were wrongfully taken from their families by an underfunded welfare system.

The child welfare case brought by activist Cindy Blackstock and the Assembly of First Nations goes back to 2007. It was not until 2019 that the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal ruled the federal government should pay $40,000 to each of the victims and their families.

The federal government is now pursuing an appeal to that ruling. Government of Canada lawyers argue the tribunal’s decision is deeply flawed, and a federal court judge is now hearing the case.

Ironically, less than a week ago, the House of Commons passed a non-binding NDP motion calling on the government to stop fighting Indigenous child victims. Most MPs — including Liberal MPs — voted in favour. The ministers with direct responsibility for Indigenous matters abstained, and now we know why.

Plus ça change, plus ça reste la même.

A road map for genuine reform

For decades, successive Canadian governments have shown themselves to be good at symbolic gestures when it comes to Indigenous peoples, but not so good at practical and tangible reforms.

There have been many commissions, inquiries and reports, including the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The Trudeau government promised to take on all of the TRC’s recommendations, but has so far only acted on a small handful.

Going back a quarter century, another commission — the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) — provided a detailed roadmap for a root-and-branch reform of relations between the larger Canadian society and Indigenous people. That roadmap is still valid today.

Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government set up RCAP in 1991, following the Oka Crisis of 1990. It named George Erasmus, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, and Quebec Justice René Dussault as co-chairs.

The commissioners did a thorough job. In 1996, they submitted a massive report to Jean Chrétien’s Liberal government, which promptly put it on a shelf. Every subsequent government has also ignored it.

RCAP’s language was frank and blunt and its recommendations were almost revolutionary. They were the most far-reaching recommendations of any royal commission in Canadian history.

Just read these words on the role — or lack thereof — Indigenous people have historically been allowed in Canada’s governments:

“To date, Aboriginal people have been prevented from playing an active role in sharing the governing of Canada; they have not been adequately represented in the federal structures of government…In the period before Confederation, it was widely assumed that Aboriginal people were simply inferior or were to be excluded on grounds of their lack of ‘civilization’ and that they had to become assimilated before they could enjoy the benefits of citizenship.”

The report points out that of the 11,000 members elected to Parliament from 1867 to 1996 only 13 were Indigenous. One of its proposed solutions would be to provide for a number of reserved seats in Parliament for Indigenous MPs. New Zealand does this for its Maori people.

RCAP also told the government it should create a third, Indigenous chamber of Parliament:

“This third house would provide a means for the Aboriginal peoples of Canada to share in governing the country, while at the same time acknowledging the distinct interests, cultures and values of Aboriginal peoples.”

More important, RCAP wanted Indigenous nations to constitute a distinct order of government in Canada, alongside the federal and provincial governments. It envisioned 60 to 80 such nations, which would cover extensive territories and have genuine powers, analogous to those of the provinces.

What RCAP proposed would be quite different from the small and isolated reserves which were foisted upon Indigenous peoples by the archaic and colonialist Indian Act.

The Cree and Inuit governments of northern Quebec, created as a consequence of the James Bay Agreement of 1975, give some sense of how such a system could work in practice.

In its long-delayed response to the Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls the Trudeau government wrings its hands in worry over the possible impact of massive resource projects, such as the Trans Mountain pipeline, on vulnerable First Nations communities.

The government alludes to the need to protect Indigenous women and girls from a massive invasion of outsiders in temporary work camps, but it proposes nothing specific as a remedy.

Were the territories through which pipelines traveled or upon which mines were dug controlled by robust and properly resourced Indigenous authorities, the dangers the government correctly foresees would be much reduced.

The temporary residents of work camps would not be a law unto themselves, or subject to the dubious discipline of the RCMP or provincial police. They would be subject to Indigenous rules, enforced by Indigenous police.

An expanded land base and benefit from natural resources

RCAP had much to say on the crucial matter of land and resources. Had we heeded the Royal Commission’s advice 25 years ago perhaps the story of Indigenous people in Canada would be a far happier one today.

RCAP points out the lands Canada currently (both in 1996 and today) acknowledges as Indigenous make up a tiny portion — less than one half of one per cent — of the country’s total territory.

We Canadians like to feel smug compared to our American neighbours, but when it comes to an Indigenous land base, the U.S. does far better than Canada.

Although Indigenous people are a far smaller percentage of the population in the U.S. than in Canada, in the U.S. they have three per cent of the total land, six times the Canadian total.

RCAP cites the Navajo nation of Arizona as an example. All of the reserves in all of Canada, it says, “would not cover one-half of the reservation held by Arizona’s Navajo Nation.”

The remedy is to vastly expand the Indigenous land base, but that alone would not be sufficient. Indigenous peoples must be given control over the lands and resources.

“Aboriginal people must have self-governing powers over their lands, as well as a share in the jurisdiction over some other lands and resources to which they have a right of access,” reads the commission.

The commissioners insist this land and resource policy would be “both a matter of justice — of redressing past wrongs — and a fundamental principle of [a] new relationship with Aboriginal peoples.”

The commission report goes into considerable detail about how to achieve a land and resource base for Indigenous people, taking into account both Indigenous systems of land tenure and contemporary economic realities.

It also outlines a grass-roots-based strategy for Indigenous economic development, which makes room for community- and cooperatively-owned social enterprise, as well as private business.

The current economic model for Indigenous communities is almost entirely based on the needs and whims of private, for-profit businesses, headquartered far from the communities.

When corporations seek to extract and exploit resources on traditional Indigenous territory the best First Nations people can expect are what Canadian officials call “impact benefit agreements.”

Weak and isolated Indigenous reserves get to negotiate a handful of jobs and some other financial benefits — many of which are more theoretical than real — with giant, trans-national corporations.

Those corporations often work hand-in-glove with revenue-hungry provincial governments. It is anything but a level playing field.

This is the aspect of the Indigenous relationship with the rest of Canada that too rarely makes the headlines.

In a perverse way, it serves the interests of corporations and the governments that collude with them for us all to focus on the horrors of residential schools or the child welfare system.

It allows our leaders to substitute abject apology for respectful and meaningful action.

We have known for decades what it will take to rewrite the future history of Indigenous nations in Canada.

But for a federal government to take the course of action the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommends would require taking on massive and powerful economic interests.

Those interests include oil and gas and mining companies and provincial governments jealous of the sole authority the Canadian constitution assigns them over natural resources.

The pay-off would be a lasting and just settlement with the more than 1.5 million Indigenous people in Canada.

So far, no government of any political stripe has shown the courage to even take the necessary first step.

Karl Nerenberg has been a journalist and filmmaker for more than 25 years. He is rabble’s politics reporter.

Image credit: GoToVan/Flickr