On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot dead while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

Most Canadians, even those with little knowledge of American history, will know King as a leader of the African-American civil rights movement, a Christian minister and a proponent of non-violent civil disobedience. And many will be acquainted with the public address with which King is most closely associated, the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. in August 1963.

The version of King commemorated on the third Monday of January each year in the U.S. — the version Canadians will be familiar with — is that of a prophetic, revolutionary voice tamed and made safe for an America — and a world — still characterized by racial, economic and social injustice. As African-American philosopher Cornel West has said, “Martin has been deodorized, sanitized, sterilized by the right wing and neo-liberals to such a degree that his militancy is downplayed.”

On April 4, 1967, a year to the day before his death, King departed from his message of civil rights to deliver a speech against America’s war in Vietnam. Standing at the pulpit of Harlem’s historic Riverside Church, King denounced the war, connecting his government’s military adventures abroad to the failure of the war on poverty at home. The programs designed to house the homeless, feed the hungry and provide jobs for the unemployed — “the real promise of hope for the poor — were starved for cash as the war effort was ramped up.

As King said that day, “I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic, destructive suction tube. So I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such.”

He argued that America must “undergo a radical revolution of values” for “when machines and computers, profit and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

King’s criticism of U.S. imperialism, his commitment to ending poverty, and his belief that the promise of civil rights could not be fulfilled without economic and social rights did not endear him to a broad swath of the American public. In the months before his death, his disapproval rating stood at 74 per cent; among black Americans it was 55 per cent.

In the wake of his ‘Beyond Vietnam’ speech, some mainstream civil rights leaders distanced themselves from King, fearing he had aligned himself too closely with the radical left of the Black Power and peace movements. The Washington Post declared: “King has done a grave injury to those who are his natural allies … and … an ever graver injury to himself.” In denouncing the war, he had denounced a president — Lyndon Johnson — who had taken political risks in supporting civil rights legislation. Financial contributions to King’s civil rights organization dried up. “I’d rather follow my conscience, than follow the crowd,” King replied.

This is the King we seldom hear from today, the King who called for a “radical revolution of values.” His message is a moral beacon, a light whose source may have been the black church, a prophetic Christianity forged amid the struggle against American apartheid more than 40 years ago, but it illuminates the dark corners of Canadian democracy today.

In Canada, we have spent $11.3 billion on the mission in Afghanistan, yet in the latest federal budget there was little for the 3.2 million of our fellow citizens who live in poverty.

We can afford to spend upward of $25 billion on new fighter jets to patrol the skies, but do not have the money to address the crisis of affordable housing that leaves so many Canadians homeless or precariously housed.

We live with racial inequalities — for example, racialized Canadians are three times more likely to live in poverty than other Canadians and in Toronto black males are three times more likely to be carded by police — yet do little to address institutionalized racism in our labour markets and criminal justice systems.

One in five aboriginals lives in poverty and many live without access to basic necessities such as electricity and clean water. Schools on reserves face funding gaps between $2,000 and $3,000 per student each year compared with provincial schools. Yet we have a prime minister who is more eager to greet two visiting pandas from China than First Nations youth who have trekked some 1,600 kilometres to Parliament Hill.

Too many of our political leaders have become well adjusted to injustice. Too many are willing to sacrifice equality and dignity for all on the altar of free markets and the national security establishment.

In that same speech at the Riverside Church, King said, “These are revolutionary times … people all over the globe are revolting against old systems of exploitation and oppression, and out of the wombs of a frail world, new systems of justice and equality are being born.”

From the Arab Spring to the global movement to end violence against women and girls, from anti-austerity protests in Europe to Occupy Wall Street, from rebellions of urban youth in France and the U.K. to indigenous struggles in the Americas, once again people are on the move the world over. We are waiting for new systems of justice and equality to be born.

At home, student protests in Quebec, union demonstrations for labour rights and, perhaps most important, the Idle No More movement, have questioned a social and economic order that benefits the few at the expense of the many.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision of a world free from poverty, racism and militarism is a universal one. His is a legacy worth wrestling with as we forge the path to a more just society.

Simon Black is a researcher at the City Institute at York University and a member of Peel Poverty Action Group.

This article was originally published in The Toronto Star and is reprinted here with permission.

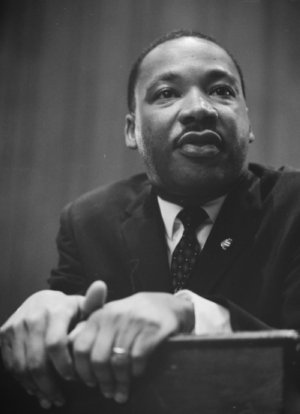

Photo: Library of Congress