Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a monthly supporter of rabble.ca.

One of the experiences that propelled me into the migrant justice movement occurred thirteen years ago when Bilquis Fatima, a 64-year Pakistani refugee in a wheelchair, was reported to immigration officials during her dialysis treatment at the hospital. She was incarcerated with her son Imran, a minor, for over a month while awaiting deportation.

The very real experiences of thousands of migrants like Bilquis who are afraid of accessing healthcare, who are unable to enroll their children in school, who are denied access to food banks, who are ineligible for a range of social assistance benefits, who are detained by local police forces and turned over to immigration enforcement has underscored the critical and urgent need for Sanctuary City movements.

Over thirty U.S. municipalities have been pressured to adopt City of Refuge ordinances that prohibit municipal employees from requesting or sharing information about immigration status when providing city services. In Canada in 2013, after over a decade of grassroots community organizing and mobilizing across service sectors, the city of Toronto declared that all city services would be accessible to undocumented migrants and migrant workers. Hamilton soon followed suit in February 2014.

Calls for a Sanctuary City have been made in Vancouver at the policy level and by service providers since at least 2005, but are now finally taking root with the leadership and persistence of grassroots groups like Sanctuary Health. Leading up to the municipal election, parties and politicians have also weighed in on the discussion.

Vancouver as Sanctuary City: A City of Inclusion or Displacement?

Last night, Vision Councillor Geoff Meggs hostied a campaign forum on how Vancouver can be a more inclusive city for migrants, including a discussion on Sanctuary City. But beyond the city’s sloganeering, political opportunism and false promises, accompanying every election lies a far more critical question about the city’s role in displacement, inclusion and safety for its residents.

The same Councillor Meggs has recently been defending a proposal to increase fines for homeless and low-income people sleeping outside and for street vending. Tickets for minor bylaw infractions already place a triple burden of criminalization on poor people in the DTES. DTES residents are most likely to be selectively profiled by the VPD for ticketing with 95 per cent of all street-vending tickets in the entire city being issued to DTES residents; DTES low-income residents are least able to afford these egregious fines; and DTES residents are most reliant on survival economies such as panhandling and street vending. “The majestic quality of the law forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under the bridges, to beg in the streets and steal bread,” Anatole France said in the early 1900s, remarking on the false neutrality of poor laws.

By atrociously stereotyping and linking street communities to crime and public disorder, these so-called civility bylaws provide the pretext for gentrification’s removal of poor and homeless people — isproportionately Indigenous and of colour — from public space. Frequent ticketing blitzes in the DTES are just one part of the intensifying processes of policing and neoliberalism facilitated by the City.

According to researcher William Damon, the Vancouver Police Department — notorious for over-prosecuting and under-protecting Indigenous women — has a $235 million police budget, the largest and fastest growing part of the city budget. Metro Vancouver’s Skytrain police budget has also grown to $31 million annually and is expected to grow 25 per cent over the next few years. Mexican migrant Lucia Vega Jimenez, who committed suicide in December 2013 after one month of incarceration and a pending deportation, was initially detained by Skytrain police for an unpaid transit ticket. Skytrain police routinely collaborate with the Vancouver Police Department and Canada Border Services Agency to identify and detain people under the pretense of fare evasion. They are also the only armed transit police force in the country.

Simultaneously, a series of intentional neoliberal policy decisions has made this city one of the most unaffordable in the world. Under subsequent municipal governments, renovictions have been facilitated, corporate developers have been incentivized, and calls for rent control have been ignored. All of these policies disproportionately impact Indigenous people, recent migrants, queer and trans communities, women fleeing violence, and seniors.

For example, after a three year Low-Income Area Planning Process (LAPP) in the DTES, ostensibly framed as “engaging” residents and community stakeholders (I was part of a group with a seat on the LAPP), the City approved a 30-year plan for the neighbourhood that includes 8,850 new condo units and 3,300 high income renters while dispersing at least 3,350 low-income residents out of the DTES. Furthermore, without a definition of social housing in the plan, let alone a guarantee that all social housing will be at welfare rates, “affordable housing” becomes a hollow declaration and perfected media sound-byte. Despite Mayor Robertson’s oft-repeated campaign promise to end homelessness by 2015, Vancouver’s homelessness count has actually doubled in the past year.

How can a municipal government that has recently approved a displacement plan for low-income DTES residents, overwhelmingly Indigenous and of colour, be entrusted to provide access and safety for displaced nonstatus migrants and refugees? This reveals not only the hypocrisy of the City government but also a logical fallacy. A city that cannot even provide the most basic human need of housing and shelter to its residents is, arguably by definition, not a city of sanctuary. This is further pronounced by the fundamental reality of Vancouver as an occupying city, one that has immorally and illegally built itself on the displacement of the Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm), Tsleil-Wauthuth (Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh) and Squamish (Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw) nations.

Towards Solidarity and Community Control

There will always be tension between democracy as the exercise of a shared power of thinking and acting, and the State, whose very principle is to appropriate this power.

– Jacques Rancière

There is no doubt that Sanctuary City is a necessary social movement to ensure life-sustaining services to migrants with precarious legal status whose bodies are vilified and whose labour is invisibilized. We need to be organizing to create community spaces where undocumented migrants can access critical services without the threat of deportation. We need to envision neighbourhoods where all residents can be supported in having their basic needs, such as housing and food, met on their own terms. We are obligated to decolonize our relationships to Indigenous communities and lands. As Alejandra López Bravo of Sanctuary Health notes in a recent Tyee interview, the promise of Sanctuary City campaigns is to further a “shift in culture, to be able to see people as people and not as different categories of people who are deserving or not deserving….Sometimes we think of Canada as a very humanitarian place that is very diverse and inclusive. We have to realize that this is not the case for many people that live and work here.”

There have been four consistent lessons for Sanctuary City movements from various U.S cities as well as Toronto: declarations of sanctuary by municipal governments are only meaningful if they are accompanied by clear implementation strategies and accountability mechanisms; victories must be defended by our communities to prevent them from being rolled back; our political power lies in challenging, not appealing to, power; and zones of sanctuary are actively constituted not by politicians but by us — as service providers, educators, healthcare professionals, and neighbours — on the basis of solidarity and mutual aid.

While the current iterations of Sanctuary City may appear novel, we can draw inspiration from a vibrant history of reciprocal relations that have been fostered amongst and between communities. I am reminded of the graciousness of the Musqueam who harboured Chinese migrants during the city’s race riots over one hundred years ago. And more recently of the DTES’s unsanctioned peer-run safe-injection site that courageously supervised over 3,000 injections in 2003 in the face of government inaction during a health crisis and HIV and Hepatatis C epidemic.

In the compelling words of Fariah Chowdhury, a cofounder of the Shelter Sanctuary Status Campaign and No One Is Illegal-Toronto organizer, Sanctuary City is as much a process as a goal:

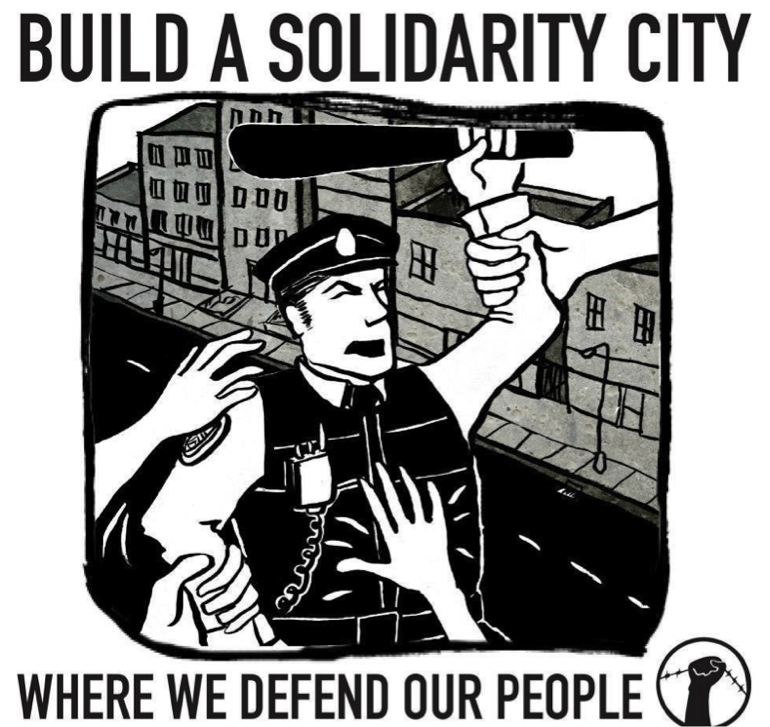

“On the question of municipal politics, no, we don’t think it has a role to play in winning these changes. In fact, that’s the very notion we are trying to fight against….If we expect that politicians and governments can change and pass desirable policies when we push them to, we not only reinforce the idea of a benevolent nation-state as a supreme entity in control, but we also disempower ordinary people, who should be the true decision making body….In a Sanctuary/Solidarity City, ideas don’t have to get passed at the ‘top’ in order for them to manifest themselves in our day-to-day lives. Sanctuary City is about building ways of living that allow us to horizontally make decisions with collective communities, on the ground, every day, with or without the approval of a colonial state that we believe is an illegitimate occupying force.”

We build a Sanctuary City by dismantling the colonial, capitalist and oppressive city we live in, by enacting intentionally just relations with Indigenous nations whose lands we reside on, and by nurturing interdependent communities committed to Indigenous, racial, migrant, gender, economic, disability, reproductive, and environmental justice.