Last night, I stopped watching the Super Bowl to watch Egypt instead.

Recently, I have been spending my nights glued to the computer monitor instead of sleeping — literally fighting off sleep — watching the Egyptian uprising online.

I, as it seems like thousands of others, have been scrolling through Twitter desperate for news.

And even more desperate to find a livestream to watch firsthand.

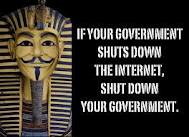

On Twitter, we furiously trade links to working live feeds like it’s our duty. I feel I am contributing a smidgen to the journalistic effort to get the story out of Egypt to the “outside world” the way a year ago I helped to push forward ways for Egyptians and the “rest of the world” to bypass strict state controls over the Internet. I know I am not doing much, but at least I’m doing something.

And judging by the number of people also watching these livestream feeds from across the world — with a solidarity shout-out from across the globe — I’m not the only one watching. Perhaps the revolution will not be televised, but will be it livestreamed?

The upside: you get to see footage live without any sort of editorialization.

The downside: it isn’t always clear what was going on.

There is a strange in-between feeling of watching an uprising on live stream. With media globalization, we’ve never been so close and yet so far away and helpless.

I don’t speak Arabic. Not a clue. I had to Google how to say “Solidarity” and cut and paste that into my chat browser. I later got a laugh when someone asked if they “speak Egyptian in Egypt?”

And unlike Hollywood movies, there was no special magic that allows for everyone to speak English regardless of where they happen to be in the world. There also isn’t that Hollywood narrative a la Battle Los Angeles where you know who and where to watch.

Here I was watching from Toronto to the streets of Cairo — an apartment building on fire, flames breaking through a window to the sound of chanting below on the streets.

Then all of a sudden yelling as those on the street became surrounded by smoke which we could later see was from police tear gas canisters.

And then a chaotic camera angle when our videographer — nameless — takes off running.

Next, a street scene of people milling about on the street away from the gas, both men and women, to the soundtrack of low decibel booms. They are standing on a major street, an inner city thoroughfare somewhere through the city. Between the groups of women walking, you can see clusters of men with their faces covered, standing still.

More booms. It sounds like shelling or multiple explosions in the distance.

The camera moves on. You can hear a call to prayer or people singing. I can’t tell but the sound is melodic.

And then we’re back at the building where a fire crew has arrived. There is a lighter moment when the fire crew inside that building accidentally sprays the fire personnel on the outside ladder with their hose. I can hear laughter from the street, but it’s quickly over. More explosions in the distance are heard.

I can feel myself falling forward into the computer screen. Whoever was the man running the livestream in Cairo from just blocks away from Tahrir Square, when he suddenly got bombarded with tear gas smoke and started running, there I was at home cheering him on. Run run run! Go go go!

Run. The authorities are coming. I’m always scared knowing that if the feed suddenly goes blank, I’m expecting the worst.