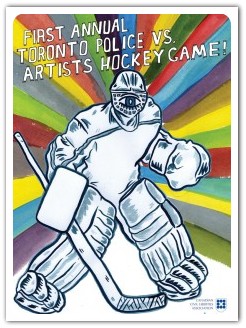

The Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) hosted the first annual Toronto Police vs. Artists hockey game on October 18 2013, taking place at the Mattamy Rink in the fomer Maple Leaf Gardens. After the hockey game there was a panel discussion at the 519 Church Street Community Centre entitled Freedom to Create: Art, Freedom of Expression and Power.

In the lead up to the event, the CCLA asserted that, in the fallout of police brutality during the G20 protests, “animosity and generalizations [about the police] are not helpful.” They added that this event was about “building bridges between communities that seem to share little common ground” and would be “an important step in dialogue.”

I, on the other hand, believe the exact opposite is true.

Last year, when I was running a youth basketball program in a low-income neighbourhood in Hamilton, Ontario, my managers proposed the idea of bringing in some police officers to the community centre to play basketball with the youth.

The managers thought this would be a fantastic way for these youth to “build bridges” with the police and to stop stereotyping all officers as “bad” individuals. My coworker and I, who incidentally were the only two people of colour in attendance at this meeting, were speechless.

I had to explain that the neighbourhood we were working in had been subjected to various efforts to “clean up the streets,” and this meant that the majority of youth had been stopped, harassed, intimidated, threatened or assaulted by the police.

I had to explain that the youth in this area were often seen as “thugs” and “hoodlums,” and that because the majority of the youth attending the basketball program were youth of colour, this meant that they were even more likely to have had negative experiences with the police.

It was two years ago that Pamela Markland and her eight children in Hamilton were subjected to a police raid on their home that saw a flash grenade thrown at Pamela’s nine year old son with autism, as well as the handcuffing of him and her other seven children.

Earlier that year, 19 year old youth Andreas Chinnery was gunned down by Hamilton police in his East end apartment. Most recently, Steve Mesic, a man suffering from anxiety who had checked himself out of a mental health care program at a local hospital, was found wandering through traffic on a highway, after which he was shot several times and killed just outside of his own home.

And these are just some of Hamilton’s publicized incidents of police violence — here in Toronto few can forget the devastating murder of Sammy Yatim that took place just this summer, or any of the others, like Junior Manon and O’Brien Christopher-Reid, both dead at the hands of the Toronto police.

Any person who has been through police violence will tell you how triggering it is to be around police officers. Or how when one’s family members, friends or acquaintances have had negative experiences with police, those triggers can still exist.

So by bringing Hamilton police into a basketball gym with young people who have suffered at the police’s hands, my managers would be jeopardizing the mental health and safety of the majority of players. They would be taking the basketball gym, a place that is a sanctuary for so many young people, and making it unsafe.

How do I know this? Well, when the idea was suggested, I thought the best thing to do would be to ask the youth what they thought about it. And the responses were unanimous. The police were not wanted.

When prompted, some youth spoke at length about their experiences being stopped and assaulted by police — others got a pained look in their eyes and simply said they wouldn’t be comfortable.

We also discussed why the non-profit organization I was working for and the Hamilton Police Services would be interested in partnering and having this basketball event. Not surprisingly, the youth at the gym had a pretty clear perception of its purpose: a publicity stunt for the non-profit and the police, who could claim they were “building community,” when in fact poor communities often have to rally together against police violence.

In fact, some of the youth rightly noted that the police might use the event to try to make friends with a few of the youths who they could then try to use as informants; quite the opposite of community building.

So back to the CCLA’s Toronto Police vs Artists hockey game. As in Hamilton, the event was framed as “building bridges” and “dialogue,” but I see nothing that would suggest this to be true, just as it wasn’t true for the young basketball players in Hamilton.

The CCLA exists to defend the human rights and civil liberties of Canadians, with a lot of their work focusing on the police. They ostensibly advocate on behalf of those affected most by police brutality, harassment and violence — meaning people of colour, First Nations, Queers, people living around and under the poverty line and sex workers.

As noted previously, many of the members of these groups would not feel safe at an event like this, as being around police is extremely triggering to survivors of police violence, as well as to those who have had friends, family members and acquaintances hurt by the police.

A great deal would also not show up simply because those who have been, and continue to be, victimized by the police likely have no interest in playing hockey with them! Before they can even get to that point, there has to be accountability for the police’s actions and significant guarantees that these actions are going to change.

So how can the CCLA claim to have been “building bridges” when those that are the most important here — the survivors of police violence — weren’t included?

Now it’s not that dialogue with the police isn’t needed — it can be an integral part of the healing process. But, you can’t have a genuine dialogue when one side holds all the power and has shown no indication in sharing that power with the community it ostensibly exists to protect and serve. And when that “dialogue” is not accompanied by substantial guarantees of change, recognition of past and ongoing abuses, and acknowledgment by the police that what they have done to our communities is destructive –it begs the question, who is the dialogue really serving?

Are those who have been victimized by the police actually benefiting from an event like this?

It makes me wonder whether the CCLA organizers recognized what a privilege it was to be able to put on and attend an event like this. Did they not look around and realize that the people who felt comfortable playing hockey alongside police tended to be those who have never had to experience police violence?

By hosting this event, which seemed like nothing more than a publicity stunt, the CCLA has alienated the people it exists to serve. Advocates and survivors of police violence in the community, who have been active for years on police accountability and transformation of policing in our society, expressed their concerns over this event. They saw it is an act of betrayal that directly undermines and discounts their work in rallying together and responding to police violence.

The CCLA heard their voices loud and clear — but instead of heeding the call of the survivors and the grassroots, and canceling the event, it went ahead as planned.

I’m sure they had a good turnout, with lots of photo-ops. And I’m sure in the discussions folks found common ground in their opinions about the police. It’s just a shame that the people who matter the most in the conversation were kept out.

Riaz Sayani-Mulji has been a youth worker in Hamilton for the past five years. He is currently a J.D. candidate at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law.