Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a monthly supporter of rabble.ca.

Without an announcement or any consultation, it appears that the federal government has decided to quietly collapse Canada’s national literacy and essential skills network. This is happening at the same time as community literacy programs across Canada experience a seismic shift and uncertainty of sustained operations, while millions of dollars in federal funding is being effectively diverted from federal-provincial Labour Market Agreements and redirected to the unproven Canada Job Grant program.

Canada’s literacy and essential skills sector is largely comprised of people who work to help others, especially our most vulnerable citizens. Many adult literacy practitioners are now uncertain about their future, and the futures of those they help. There have been increasing reports of staff layoffs in community literacy agencies across the country over the past few months, and we know that this is also happening in many of the federally funded national and provincial literacy organizations, including CLLN.

In Canada, adult literacy instruction is sometimes delivered by community organizations, sometimes in a formal school setting and sometimes it is incorporated into workplace training. Responsibility for managing and funding adult education and training varies greatly across Canada’s 13 provinces and territories.

This diversity creates richness in our field but also presents a number of serious challenges. For example, it is difficult to compare adult literacy and essential skills programs across jurisdictions, evaluate their effectiveness and track results. The sector’s workforce is not organized as such (although some may be a member of a union or association), so the layoff of possibly hundreds of people is not making headlines.

How did this come about? Where is the public policy discussion? Here are the facts as we know them.

Early in 2013, the federal government published a Call for Proposals (CFP) to create a new “pan-Canadian network” to support adult literacy and essential skills. Based on previous consultations carried out by the department (formerly Human Resources and Social Development Canada, now Employment and Social Development Canada), the CFP presented a fairly clear vision of the expectations the government had for this new network.

Specifically, the CFP defined four components that would comprise the new network: Information and Resources, Connections, Innovation, and Research. Proposals were due in May 2013 with new agreements expected by November–but the decision was delayed, and delayed again.

With the current federal funding for 22 organizations expiring on June 30, letters finally started arriving mid-May 2014, informing the unsuccessful applicants that their proposals would not be funded. Several of these organizations had already issued layoff notices.

A Calgary Herald story about layoffs in the sector quoted an email message from Alexandra Fortier, press secretary to Minister of Employment and Social Development, Jason Kenney. She said that federal funding had been “going to the same organizations to cover the costs of administration and countless research papers, instead of being used to fund projects that actually result in Canadians improving their literacy skills.

“These organizations were advised three years ago to give them ample time to prepare (for) the federal government changing the structure of funding through the Office of Literacy and Essential Skills to make it more effective. Canadian taxpayers will no longer fund administration of organizations, but will instead fund useful literacy projects.”

We challenge these statements on several points.

First, the literacy organizations were certainly not prepared for federal funding to end. While the previous network model was in need of some overhaul, no one anticipated a wholesale dismantling. The groups responding to the CFP did so in good faith, and with a great deal of thought and effort, believing that the government intended to follow through and implement a new network after decisions had been made. Proponents were not prepared for the government to delay and then abandon its own process.

Second, about “useful projects”: project-based funding has been clearly identified as one of the major problems with Canada’s approach to literacy and essential skills program development and delivery. There have been many highly innovative and successful programs developed in Canada, but once the pilot funding ends, the project closes.

It’s also worth mentioning that HRSDC/ESDC has not been spending its literacy project budgets for many years, lapsing millions of dollars annually.

Canada needs to develop a mechanism to identify, scale-up and roll-out the most innovative and successful projects as programs operating across jurisdictions where they can be effective. This has been an area of focus for CLLN over the past few years. Without a national umbrella network to do this work, how will it be possible to maximize the value of the government’s investment in these projects?

Third, the value of “administration and research”: some administrative overhead is required to have effective national organizations and is not de facto a poor use of taxpayer dollars, especially when compared to the overhead costs of running government programs. “Research” was one of the four key functions of the proposed new network; it is disturbing to see the value of research summarily dismissed by the Minister’s staff.

The results of the recent OECD international study of adult skills show Canada languishing in the middle of the pack. The OECD’s key points for policy development include a broad range of observations on the importance of flexible labour market arrangements, incentives for employers and accessible lifelong learning opportunities.

The European Union is making significant investments in adult education — across jurisdictional and linguistic barriers more complex than Canada’s — with a focus on accessible lifelong learning, improving professional networks and sharing effective best practices. These are similar to some of the program directions CLLN proposed to pursue.

In Canada, the focus now seems to have narrowed to “closing the skills gap” by training workers for high-demand jobs, rather than “elevating the skills level” of Canadians, so there will be a larger pool of talent ready to take advanced training.

Without a strong essential skills assessment and upgrading component — and this has not been a prominent part of the discussion to date — many advanced skills training programs are not appropriate for Canadians with low foundational skill levels. Either they will not be considered as eligible candidates for a placement or they may not successfully complete their training programs.

Without any announcement, it appears that the federal government is simply going to defund the national literacy and essential skills network, and hope it goes away quietly. So far, that is what has been happening, as the various agencies clung to the hope that their good work was worthy of at least some of the $5 million per year that the government had budgeted to spend.

But it has become clear that there will be no national strategy on adult education, no inter-jurisdictional council on adult education and training, no national network of non-profits working in literacy and essential skills, and, apparently, not much research. It’s not just the literacy and essential skills sector that the federal government is abandoning — it’s also the most vulnerable low-skilled Canadians.

Board of Directors

Canadian Literacy and Learning Network

This statement originally appeared on Canadian Literacy and Learning Network and is reprinted with permission.

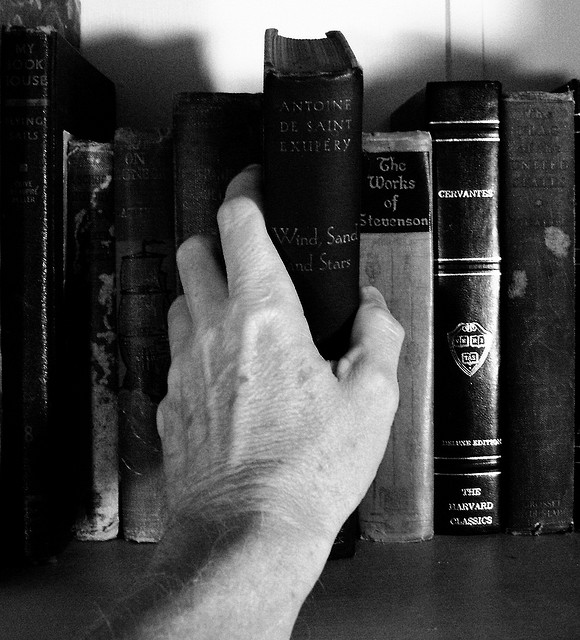

Photo: flickr/Patrick Feller