In the last section of his Republic, in which Plato outlines his designs for the ideal society, the great philosopher famously banishes poets from the city, the polis. The problem is, you see, they’re a bunch of fakers. They pretend to know everything and anything, but in reality, they’re know-nothing scoundrels. They drink, they fight, they carry on — and they’ll corrupt the public with their chiasmuses and villanelles if we’re not careful. So, sorry poets: you’re out.

Of course, a cynic might say that government already has enough inveigling dastards besmirching the good offices of the polis. Maybe it’s time to offer these poet nogoodniks a second chance. If you’re a resident of B.C., you have the unprecedented opportunity to put a poet close to, if not yet in, the legislature. I’m talking, of course, about NDP Leader Adrian Dix’s partner, Renée Saklikar.

“My husband gives long speeches,” Saklikar said in an interview with the Vancouver Observer. “For me, it’s the long poem.” That’s the last time I’ll mention that other guy in relation to Saklikar’s poetry, but for anyone tired of the talking points, the slogans, the attacks, in this year’s election campaign, it’s pretty exciting to take seriously the possibility that a poet might have the ear of power for the next four years (slam poets excluded, naturally).

Saklikar is still an emerging artist, but already you can see her methodology developing: documentarian, geographic carefully indexing space and time: “do you carry for yourself, a secret name — / the way a river might — / bounty learnt year by year, province by province.” Saklikar was born in India, but grew up in Quebec and Saskatchewan, so it’s easy to see why place is important to her. She writes in her native tongue, English, but her South Asian roots can lead to what she calls “language transgressions”: “Un/authorized interjection: don’t you know how to say it in Punjabi? Punjabi bolo?“

Saklkar has travelled far in many meanings of the word. She began her career as an entrepreneur, a lawyer and a public service worker, but embraced her poetic side professionally after the death of her father, New Westminister rector and community icon Vasant Saklikar, in 2002. Her aunt and uncle both perished in the Air India bombings, and Saklikar testified at the commission. She wrote an elegant and moving essay on the ambivalent findings of the commission’s final report and how they were received by mainstream Canada.

“What are the cultural and linguistic knowledge bases of the Canadian public? If those intent on ‘terror,’ that is, on acts of violence, use the trappings of ‘religion,’ of ‘culture,’ to promulgate a rationale for the taking of life, will we have the sophistication to sift through the spectacle of ‘ethnic’ practices? Will listening in on people be more than state use of surveillance and include grassroots, community-based education about the ‘other’?”

Bearing witness

And this leads to perhaps the most consistent motif in Saklikar’s poetry: documenting. Bearing witness. “I seen you,” she begins “Everyday Heresies,” published in Geist last year. “at the Tim Hortons, / at the Canadian Auto Workers Hall, / and even heard you on the CBC.” The poem begins assembling seemingly unconnected figures — East Van yuppies, Costco shoppers, professional complainers — until it becomes clear that the one “seen” is the speaker by an array of whiteness, or at least of privilege:

“Out the window of your truck, you scream: where did you get your fucking licence,

you fucking Punjab? Your words, grit

thrown into the years and —

I seen you.”

She has written about female labourers killed on the job. Her forthcoming book from Harbour Press responds to the trauma of the Air India terrorist attack with a lyric elegy for each child who died. The book’s promo blurb identifies the work’s fundamental proposition: “that violence, both personal and collective, produces continuing sonar, an echolocation that finds us, even when we choose to be unaware or indifferent.” This is her work: asking how we bear witness to something both “over-reported and under-represented” that touches the racism, trauma, security, and legacies so indivisible from Canadian national narratives. “Come,” she says. “I will tell my story.”

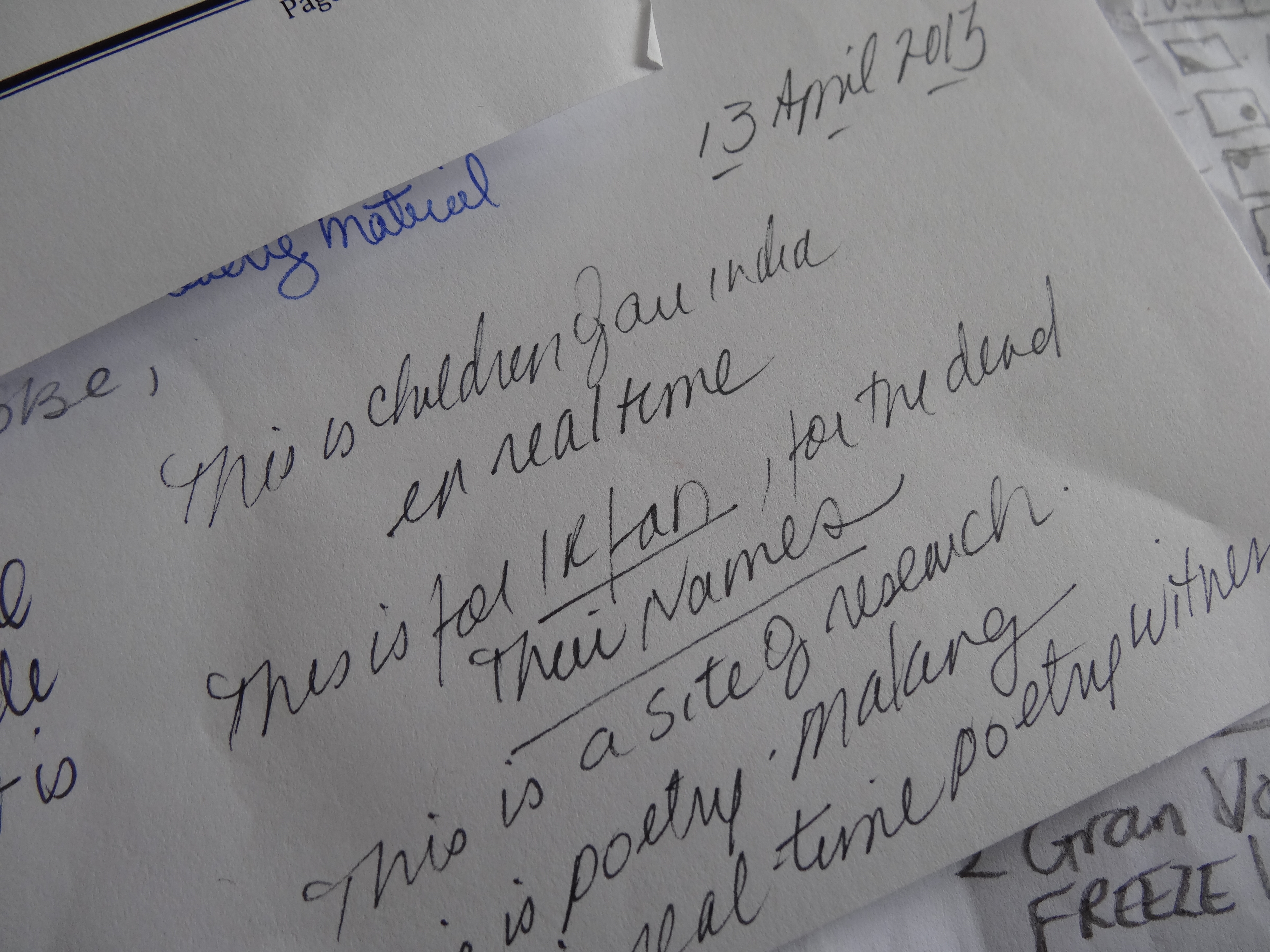

As someone who just doesn’t find Plato all that convincing and maybe even kind of a prick (did I mention he concluded that philosophers would make the best kings?), I’d just as soon dispense with hackneyed and depressing slogans like “Strong economy, secure tomorrow” and “Change for the better: one practical step at a time” (Sorry Renée) and let poets have a crack at leading this province. “This is part of a long poem,” Saklikar writes of her chronicle-poem thecanadaproject. “This is not enough time.”

If anything, when it comes to governing British Columbia, a “long poem” would be a good place to start.

Renée Saklikar’s first book of poetry, children of air india inspired by the Air India bombings, will be published by Harbour in the fall.

Photo: thecanadaproject