Karl Nerenberg is your reporter on the Hill. Please consider supporting his work with a monthly donation Support Karl on Patreon today for as little as $1 per month!

On Thursday night, this writer had just attended a concert by the Ottawa Jazz Orchestra led by bassist Adrian Cho, when he heard the news of Leonard Cohen’s death.

It had been an evening of angular, sometimes aggressive, even harsh music.

Cho had programmed pieces that, by his own account, were not easy listening. He described it as the music of Freedom Fighters, evoking the civil rights and black power movements of the 1960s.

There were no standards, no amiable tunes by Gershwin, Cole Porter or Richard Rodgers. Nor were there what one might expect under the rubric Freedom Fighters: no “We Shall Overcome,” nor, even, Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam.”

This was an evening of complex, complicated and little known, single-malt jazz, composed by the likes of Charles Mingus, Freddie Hubbard and John Coltrane.

The packed room, made up of folks who did not seem like hard-core aficionados, lapped it up.

The timing had something to do with that.

An evening of uncompromising, instrumental music of liberation, rebellion and resistance — even if little of it was familiar — seemed more than fitting, in the light of what happened on Tuesday.

Starting as a writer, Cohen became a true composer

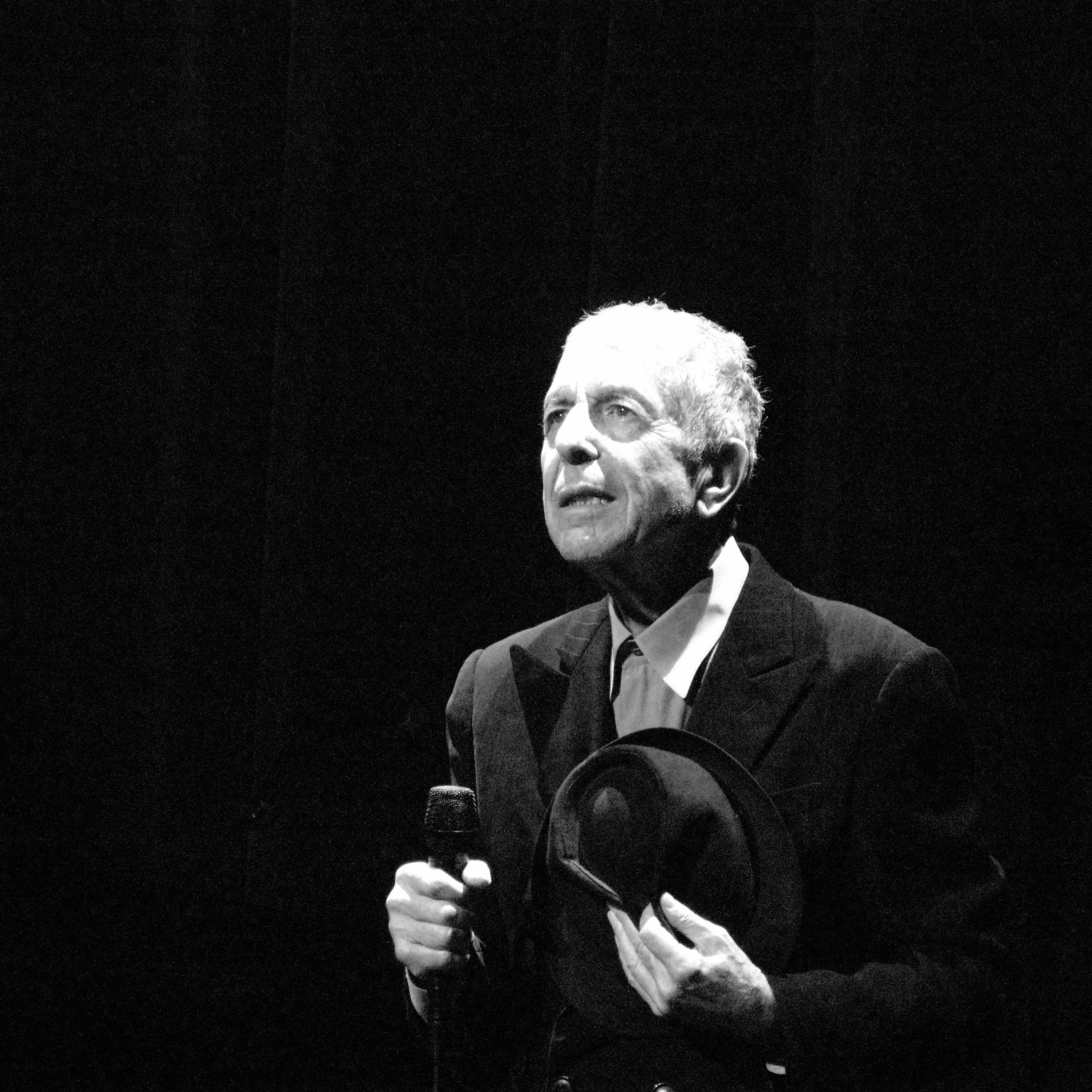

It is worth reflecting on the power of music to make a statement, all on its own, without words, in the context of the death of a quintessential artist of words: novelist, poet, songwriter and performer, Leonard Cohen.

Virtually everyone remembering Cohen today remembers the man of words, but Leonard Cohen was also a man of notes and chords and rhythms.

Like those 1960s pioneers of what we still think of as modern, avant-garde jazz, Cohen told stories with his music, as much as with his justifiably celebrated lyrics.

Donald Brittain and Don Owen did a documentary on Cohen for the National Film Board of Canada, in 1965, before Cohen had ever performed a single song of his own in public.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, Mr. Leonard Cohen” was the story of a still young star in the rarefied world of poetry — and star he was, even then. He filled houses of adoring fans for readings of his passionate and flamboyant verse.

At one point in the film, we learn that Cohen is not a high culture person. He doesn’t listen to serious, classical music, intones the narrator in the detached voice-of-God style of the time. The poet, we are told, prefers pop music.

Then there is a scene in Cohen’s three-dollar-a-night Montreal hotel room, on Boulevard St-Laurent, where the winsome and slightly shy poet strums a guitar, a bit, during an impromptu party.

It would still be a while before Cohen became a songwriter, and even longer before he would perform his own compositions in public.

But from the moment he put his earliest songs into the marketplace, other performers, such as Judy Collins, were discovering insights and truths, not only in the lyrics, but in the music itself.

Musically, Cohen’s songs were more than self-effacing vehicles, intended only to showcase his complex and multi-layered lyrics.

As a composer, Cohen took the motifs, harmonies and clichés of the pop songs on which he’d been weaned, and made them sound fresh, innovative and original.

If you can, try playing his songs as instrumentals, without singing along, on the piano or another instrument. You will find all kinds of compelling musical statements that are not apparent when you have the words.

Truth to tell, Cohen’s own interpretations of his creations, for all of their authenticity and power, do not do justice to his prowess as a composer.

The Germans have a word for it: Sprechstimme, spoken singing. Cohen did not sing so much as talk with a musical background.

It is only when you hear Cohen’s songs performed by K.D. Lang or Jennifer Warnes or Madeleine Peyroux or Rufus Wainwright that you can fully realize the power and intensity of his musical imagination.

Using familiar patterns to create novel and original sounds

Yes, Cohen was writing pop, or folk-pop, country-influenced songs, drawing from the same bag of tricks as do many other popular artists, some of them brilliant, some banal.

These days, much pop music, influenced by hip-hop, has a chant-like quality, using scales and modes that are more derived from African and Middle Eastern music than from the western tradition. Cohen’s music is deeply rooted in the western tradition, however. It works on the interplay and tension between the two essential western musical modes: the major and the minor.

As teenagers in the early sixties, this writer and his friends discovered the classic 1-6-4-5 chord pattern that undergirds thousands of fifties-style rock’n’roll songs. Think of Paul Anka’s “Diana,” Frankie Lymon’s “Why Do Fools Fall in Love,” Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me,” or The Marvelettes’ “Please Mr Postman.”

More recent pop artists have liberally used this fifties pattern. Sting’s “Every Breath You Take” and Green Day’s “Jesus of Suburbia” are just two among many well-known examples.

In actual fact, this particular musical pattern saw the light of day earlier than the rock’n’roll era. It goes back to the 1930s and 40s, with songs such as Richard Rodgers’ “Blue Moon” and Hoagy Carmichael’s “Heart and Soul.” There was a time, years ago, when you couldn’t walk into any public space with a piano without hearing kids playing either “Heart and Soul” or “Chopsticks,” or both together.

Cohen grew up with this music — even played it as a teenager as a member of a rock band.

And when the poet turned his hand to creating his own songs, the pop of his youth provided a vocabulary easily at hand. Cohen described what he was doing musically in the lyrics to what is arguably his most celebrated song, “Hallelujah”: “the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall and the major lift…”

In fact, “Hallelujah” starts out as though it is going to simply reproduce that same 1950s pattern. It pivots from the home base chord — the tonic, the one — to the relative minor, the six chord.

But then Cohen doesn’t do the expected and predictable, and move on to the fourth and fifth, and then back to home. Rather, he stays on the major-minor, back-and-forth pattern for a bit longer, as though to emphasize the enduring sense of ambivalence between darkness and light, between sorrow and joy that is so much a part of all his work. He then, in a seeming conservative, predictable way, ends his first phrase back at home base. But before you can get too complacent, he moves the song, harmonically and melodically upward.

As the verse reaches a climax, Cohen reverses the comfortable, downward, circular direction of the classic progression and moves us higher, in a yearning, never-quite-resolved fashion. For a while, he upsets the applecart by shifting home base from the light and cheery major to the dark and gloomy minor.

When Cohen ultimately resolves the repeated chorus of “Hallelujah,” it is in prayerful, dirge-like fashion, with a repeated musical phrase that reminds one of the amens at a revival meeting. The word hallelujah is, after all, Hebrew for: May the Lord be praised.

The lyrics work perfectly with this musical construction, of course. But they are not, perhaps surprisingly, necessary to its success.

In at least one other case, “Take This Waltz,” composed in the 1980s, Cohen becomes purely a composer. He puts music to another writer’s words, those of the Spanish poet Garcia Lorca, after whom Cohen named his daughter. Again, his melody and harmony rock back and forth between major and minor and build tension by suggesting phrases are about to end predictably, only to change course and turn in an unexpected direction.

There are not a lot of chords. The rhythm, like that of “Hallelujah,” is a familiar three-four (this is a waltz), and the melody relies to large extent on the frequent repetition of notes. Cohen sometimes seemed to write to accommodate his own extremely limited vocal range.

But there is a certain ineffable “rightness” — to borrow a phrase Leonard Bernstein used to describe Beethoven’s music — to Cohen’s musical creations. They seem inevitable, natural, ordained to be as they are. And that’s why folks keep singing and playing them.

Cohen the composer will probably never be the equal, in the minds of his present and future fans, of Cohen the poet and lyricist.

But we would not be reflecting on and talking about him today, to the extent we are, if there were not something profoundly original and even innovative about his music, purely as music.

Using the limited harmonic toolbox of pop, folk and country, Cohen created songs that are marked by daring and freshness. They have already stood the test of time, and they will no doubt be played for generations, even without their words.

Karl Nerenberg is your reporter on the Hill. Please consider supporting his work with a monthly donation Support Karl on Patreon today for as little as $1 per month!