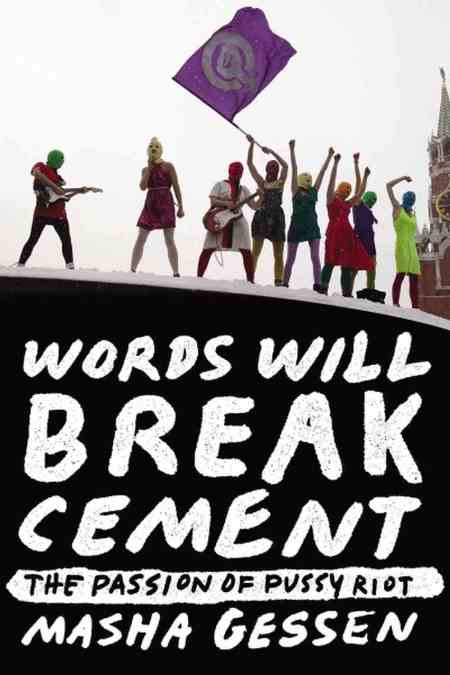

Author Masha Gessen’s new book Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot tells the true story behind Pussy Riot, a feminist Russian art collective headed by three young women named Nadya, Maria, and Kat. Words Will Break Cement has just been released at perhaps the most appropriate and crucial time, as the controversial XXII Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, Russia draw closer, and when the leaders of Pussy Riot have just concluded their time as prisoners.

What many people do not know about Pussy Riot, is that behind the neon masks and punk-band persona used to perform series of bold art installations around symbolic Russian landmarks, is a group of girls in their early twenties who have brought to the surface a virtually non-existent Russian feminist/Riot Grrrl culture, and who use their art to bravely draw attention to Russia’s urgent political state.

Gessen’s story paints a portrait of the broken social and political system of the eighty-three regions that constitute the Russian federation headed by authoritative and hyper-conservative leader, Vladimir Putin. Putin is responsible for “systematically disassembling the country’s electoral system and taking over all federal and most local television channels, so that there are is little left for opposition.” In other words, the dude wants to be in charge, and it’ll take an army to stop him. Or perhaps even more.

The story opens with a series of interviews between Gessen and Nadya’s family travelling over the course of a year while visiting Nadya at her penal colony called IK-14.

“A penal colony was the economic and architectural center of each village, with small, impermanent-looking wooden residential houses clinging to the mass of colonies’ concrete buildings and tall churches,” writes Gessen. But the colonies and prisons are much so much more. They are centers of slave labor, rape, and a bureaucratic horizontal leader system which leaves many inhabitants with futures that seems as bleak as their stark, rural surroundings.

As the novel moves forward, we are introduced to the families and pasts of Nadya, Maria, and Kat. All college educated, with a passion for art, the group was brought together with a deep, internal desire for something more–something different. Unsatisfied with the typical Russian ideal that women are destined for lies in the kitchen, Pussy Riot formed with a simple mission that would evolve into something greater than they had imagined.

But one thing was certain: to be in Pussy Riot required a full commitment. Not only to the members, but even of the members’ significant others and their children. What they were doing was dangerous, and often led to weeks or even months of living in hiding. A price they were willing to pay.

The group emerged in late 2011 after art collective, Voina (meaning “War”) headed by Petya, Nadya’s boyfriend and eventual father of her child, dissolved and the young radicals sought a new outlet for artistic expression. While Voina would push the boundaries of public space, Pussy Riot would later include a more serious and urgent narrative.

Nadya had met Kat at University, and the two spent much time scheming plans and turning their focus to LGBT equality and feminist issues. Unbeknownst to the families of the two girls, they were scheming what would become some of the most noted protests in Russian history.

In a conversation with Kat’s father, Stansilov, he tells Gessen, “They were always in Yekaterina’s (Kat’s) room. Doing girl stuff, I thought. I didn’t realize what they were up to until I got a phone call from the police.”

If by typical “girl stuff” he means studying philosophy by existentialists such as Nikolai Berdyaev, Lev Shestov, Satre, Schopenhaur, and Kierkegaar, then yes, that is exactly what they were doing.

The group which originally started under the name “Pisya Riot” (Pisya, the childish term for one’s genitals), the group practiced playing at playgrounds, and would later take the stage at venues such as metro terminals and later, world-famous Red Square. As time grew on, Pisya became Pussy, and the group was quickly gaining a reputation in not only the art community, but to the general population as well. The media was having a field day, and the group was becoming well-practiced in their craft.

Since this was clearly risky business, Pussy Riot went through several members for one reason or another. Some could not risk going to prison, others feared for their physical safety. Either way, the group pressed on, always striving to top their latest performance, and to send a clear message to the public and government officials.

Their most noted performance would be on February 21, 2012 inside the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in central Moscow. In the months leading up to Putin’s re-election, the group’s voice took a more political tone. Inevitably, Putin would serve as Russia’s leader for another term, and so ensued the rage of Pussy Riot. The line between church and state in Russia would continue to blur and drown out the voices of its people. Not if Pussy Riot had anything to say about it. In what would be their last performance, the group quickly set up their stage in the center of the Cathedral and in a performance which lasted just under a minute screamed the lyrics they had been rehearsing;

Virgin Mary, Mother of God, chase Putin out,

Chase Putin out, chase Putin out….

…All the parishioners are crawled to bow

The phantom of liberty is up in heaven

Gay pride sent to Siberia in a chain gang…

Head of the KGB, their chief saint,

Leads protesters to jail under guard

So as not to offend the deity,

Women must give birth and love

Shit, shit, holy shit!

Shit, shit, holy shit!

Virgin Mary, Mother of God, become a feminist

Become a feminist, become a feminist…

Within a week, the video of their performance had gone viral. Gessen beautifully describes the feeling of uncertainty and anxiety associated with Pussy Riot’s protest at the cathedral. The days following their performance were the calm before the storm.

“since it was clear that they needed to do further damage control, Nadya, Kat, and Maria went to an apartment — a semi-abandoned flat they had come to consider their headquarters….And just like lovers sensing those cracks often do, in their anxiety they clung together.”

They were caught, and so began the six months in prison leading to their trial. However, they would use their time locked up to learn as much as they could about the legal system and to plan their next move.

By the time the trial had begun, the group had realized that trial might in fact become their best performance yet. They used their time to give speeches stating their grievances, and their Plexiglas chambers served as stages to call people to action against the corrupt political system and to seek justice.

Media relayed the messages, and soon “The Red Hot Chili Peppers spoke out when they came to town…Franz Ferdinand and Sting issued statements of support. Then came Radiohead, Paul McCartney, Brice Springstein, U2, Arcade Fire, Portishead, Bjork, and hundreds of others.” The music industry rose to the occasion to show unwavering support for Pussy Riot unlike ever before.

By the end of the trial, Pussy Riot’s mission had shifted from just feminist messages and random political angst, to three specific things; freedom for political prisoners, ending the constant communication between government and church, and reforming the judicial system.

In the end, after days of legal torture while under trial, Nadya and Maria were sentenced to two years in Russian prison, while Kat would serve two years under probation. The official grounds for imprisonment? “Hooliganism”.

The road to achieving Pussy Riots goals would be a long one.

Through Gessen’s beautifully and historically accurate journey with Pussy Riot, the reader walks away with an overwhelming wealth of saddening and motivational information. We see the commonalities among generational twenty-somethings via Gessen’s acute observation with a heartwarming description of how awall-flower transforms into a power-house rebel and the bravery it requires.

“Political history and art history is made when someone effectively confronts a lie…and confronting these lies is the most scary and lonely thing a person can do,” writes Gessen.

And like many people in our twenties, we cope with the feeling of loneliness by compartmentalizing, and Gessen does not ignore this.

She writes about Maria, “By the time she was in her early twenties, she had, like many people who perpetually feel like outsiders, perfected the art of compartmentalizing her life.”

These chilling words describe feelings the members of Pussy Riot would eventually feel as a result of their art. Feelings of loneliness, and even sometimes hopelessness. Nadya herself quickly learned that, “When you lose your freedom, you lose, first and foremost, the opportunity to choose the company that you keep.” The children of Nadya and Maria, as well as their husbands, would only be able to visit them for four hours every two months while they were serving out their sentences.

Words Will Break Cement is a fantastic and informative read which reminds us that social and political justice should never be lost without a fight. Pussy Riot also stands for feminists around the world, and reminds us that there is no one too young, or unimportant to ignite change and action in others.

The power to change lies within us, and we always have a choice. In the words of Concentration camp survivor Viktor Frankl said, “There are two ways to go to the gas chamber: free or not free.”