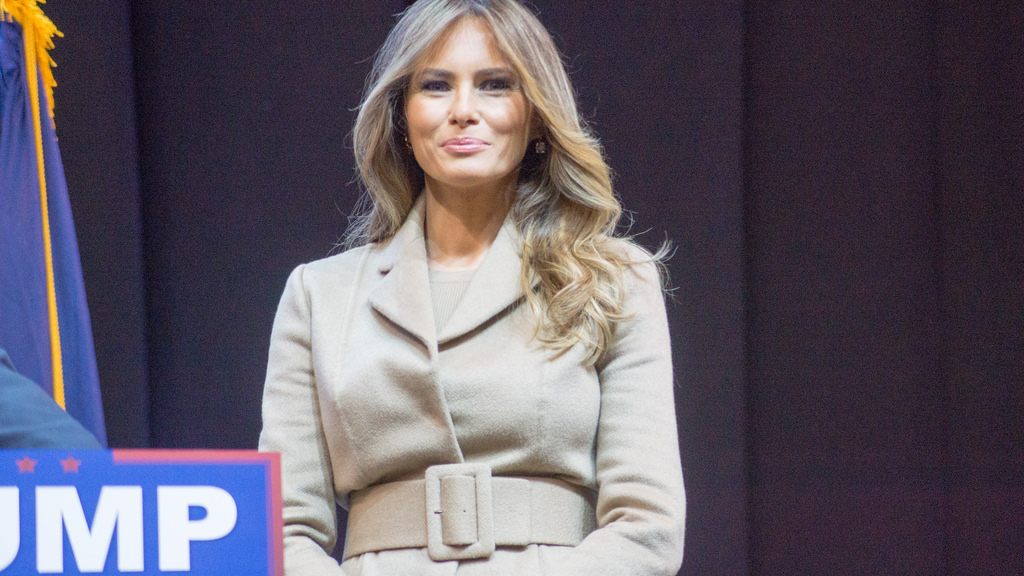

As the news of Melania Trump’s plagiarized speech came in on Monday night (parts of it sounded exactly like Michelle Obama’s communiqué delivered at the 2008 Democratic National Convention), I was counting the days until the Eastern Bloc connection would somehow be made. Or, should I say, until the ready-made Eastern Bloc stereotypical rhetoric would tease out through the North American gaze. I was waiting for something “official,” — a newspaper article, an editorial or magazine commentary, and not just the random Facebook memes and posts that called Melania anywhere from a “Slovenian immigrant with a thick accent,” to a “dumb bitch with big boobs” and “only good for blow jobs.”

I did not have to wait long. On Wednesday, a Washington Post article written by Monika Nalepa, an associate professor of political science at the University of Chicago, was quick to draw the link between Melania’s hyped up plagiarism act and the so-called culture of cheating in Eastern European schools. And here is Nalepa’s logical reasoning: since Melania is from Eastern Europe (Slovenia), and everyone cheats in Eastern Europe, Melania is, by extension, a cheater — hence, no wonder she plagiarized.

According to Nalepa, in the post-communist/post-Soviet educational system, learning implied: a) memorization (Lenin did not say in vain that repetition is the mother of knowledge); b) lack of critical questioning, since this went contrary to the state supported ideology of communism (skipping the minor detail of critical consciousness at the base of communist ideology, which is also why most critical theorists are Marxists at heart, despite the theoretical argument that the former Eastern Bloc has practiced state capitalism in lieu of political communism); and c) systematic support for cheating (backed up by the author’s personal accounts of entrance exams at University of Warsaw, as well as anthropological regional theorizations about cheaters being defined as “borrowers”); hence d) the memorization practice coupled with cheating generally led to an easy appropriation of intellectual work, also explanatory for Melania’s fraud.

In other words, Melania’s act of plagiarism had nothing to do with a personal behavioral tendency to “borrow” content, nor with the volatility of Trump’s campaign, nor with in-house staff writers’ predispositions (i.e. Meredith McIverhat, who seem to have drafted Melania’s speech as she took direct responsibility for some of the copy-pasting), but rather with the fact that Melania originates from, and studied in the former Eastern Bloc.

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek, a fellow Slovenian, argues that taking a subject to signify several properties (i.e. the Eastern Bloc attributive stereotype of cheating in our case), does not do much until the very signifier-signified relation gets inverted, and we consequently claim that someone is as such and such on the basis of their stereotypical attributes. Melania’s Eastern Europeaness becomes identified in an objective-scientific manner as explanatory and justificatory for her behavioural act(s). Saying that she plagiarized because she is Eastern European, is similar to saying, in the spirit of stretching up this nonsensical argument, that the former Toronto District School Board director Chris Spence plagiarized his doctoral thesis because his parents are Jamaican and there are some cheating tendencies in the Jamaican culture, or that former German education minister Annette Schavan plagiarized her dissertation because she is Roman Catholic, which is a religion prone to cheating. Attributive associations of Eastern Europeaness encompass just another form of “inverse racism,” Žižek argues, as they reflect the Western hatred against Eastern Europeans, and particularly against Balkan people, by propagating racist discourses that would never be tolerated against others.

Let alone the conceptual limitations that conjure Nalepa’s thoughts and frame her argument from a Western-defined East-West divide. The category of Eastern Europe can hardly be used as more than an analytical tool, since there is no consensus on what Eastern Europe really is, or on the homogeneity of the region: Central Europe claims its unique place on the map (i.e. the central European idea, initially originating from the German-centric concept of Mitteleuropa was later supported by Poland, Hungary and the former Czechoslovakia as a standalone concept and re-taken to constitute the Visegrád Group of central European states, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, for the purposes of furthering their 1990s European integration); Eastern Europe proper (Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, and Ukraine) is in continual definition about who is in and who is out of the region; and the shifting southeast subdivision of the east-central division is further pushed into a peripheral status (the so-called Balkan states that came out of the Ottoman empire — Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, Romania and Bulgaria, as well as the former Yugoslavian nations and Albania). Despite being backed up by Nalepa’s personal experience, Eastern Europe can barely be used as a de-historicized, homogenized concept.

And since personal accounts amount to evidence based knowledge at The Washington Post, I should also detail, for contradictive demonstrative purposes, my school based experience in one of these Eastern Bloc countries — Romania.

From the first to the eighth grade I attended music school, studying eight years of piano, chorus, history of music and other music related subjects (for free, since education was public). I continued with the so called academic high school (bilingual section in French) after I re-took an impossible-to-cheat exam that I initially failed in the summer, as the administration would prefer to only fill 15 out of the 30 spots rather than admit someone with a mark lower than 85 per cent.

I made the entry in the fall. My high school courses included: intensive, over 15 hours a week of French grammar, French literature and history of France (in French), English, logic, mathematics, physics, chemistry, sports/gymnastics, jointly with four year long classes of Latin, Romanian literature and universal literature, general history and history of art. My first high school essay discussed the theme of the Grotesque in Francisco de Goya’s works. The starting book for universal literature was Homer’s Iliad. My high school experience was also coupled with four years of dance intensive lessons (also at no cost; the Soviet reminiscences were much more about cultural capital accumulation in lieu of economics). Oh, and I have just remembered about the Epic of Gilgamesh, an old story from ancient Sumeria, which we were required to read even before high school, in elementary school.

For my Bachelor of Arts at one of these Eastern Bloc lower caliber institutions — not even ranked within the top 500 in the world — we read everything from Plato and Aristotle, to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Max Weber, Hannah Arendt, Norberto Bobbio, Giovanni Sartori, John Rawls, and the list could go on and on. In comparison, during my doctoral education at University of Toronto, ranked 1st in Canada, and 19th globally, I have found the readings, texts and course requirements to be well below my undergraduate education in Romania, and completely simplistic in pushing one’s general frame of thought. Let alone that no one had heard of Goya, or Gilgamesh, for that matter. Yet, North American education is held high up as the “golden standard.”

And let me also share the experience of my university entrance exam. We were about 800 people for 40 seats, there was absolutely no cheating that could have happened (we were purposely seated one person per row, with one row between us) and when the clock indicated the end of our writing time, pencils had to be down on the desk to divert the risk of having our papers annulled. I got in, number 19 out of 40, with a mark of 9.27 per cent. In North American translation — with over 90 per cent.

Personal examples could detail more. But I am unsure how much these would tackle the simplistic analytical divide that Nalepa’s article puts forward, nor the stereotypical logical reasoning, which, in a typical North American fashion, merely intends to show the backwardness of Eastern Bloc societies. Of course, Cold War reminiscences are always about denigrating the former Soviet Bloc. Yet, despite the many faults of that system, education was not one of them.