Arthur Renwick comes from two places in northern B.C. — Kitamaat, the ancestral home of the Haisla people, and Kitimat, an Alcan company town, built in the fifties to house the aluminum smelter’s workers.

To get to Kitamaat, the Haisla village, you have to turn left at the entrance to the company town, and drive 14 kilometres to the other side of the channel. There, you will find the tiny Haisla community, where Arthur spent his childhood summers playing with his cousins, and where he used to sit and listen to his grandmother Ella drum and sing in the Haisla language. She was an important elder in the Haisla village, and played a central role in keeping the community and culture alive.

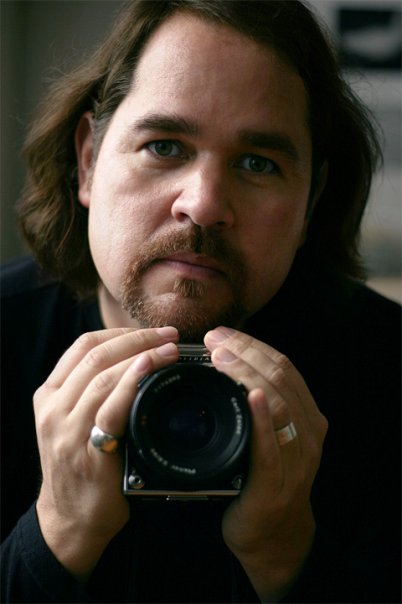

Now based out of Toronto, Arthur Renwick is an artist, musician and professor who teaches Fine Arts at the University of Guelph.

Arthur’s artistic abilities developed when he was young. He started drawing when he was six, and had a gift for super-realism — he could reproduce almost anything as a drawing. He would create likenesses of his friends, and was often asked to draw pictures for school projects. Art became his vocation when he first studied it formally in high school. When his art teacher saw his work, she announced that he could already draw better than she could. With the help of teachers and the Haisla community, Arthur moved to Vancouver and studied at the Emily Carr College of Art and Design.

By the time Arthur arrived in Montreal in 1990 to begin his MFA at Concordia University, he had already developed an artistic vision, and growing up Haisla meant he understood the political struggles of Aboriginal people.

These elements come together in a provocative way in Arthur’s photography, a recent example being his Mask series, acquired by the National Gallery of Canada this year. The series is a group of larger-than-life portraits of First Nations people who practice varying professions within the arts. Arthur asked each of them to consider the complex relationship between “the lens” and “the Indian,” and then look back through the lens to greet that complicated history with a facial gesture. The results are huge portraits of Aboriginal people looking out at the audience, distorting their faces.

Secure in the knowledge that his family and community are there for him, Arthur has travelled far from home and lived in cities across Canada. “When I came to Montreal, all I had was my guitar, a duffel bag and a 5 x 5 foot painting that a friend rolled up and gave to me as a parting gift. I drove from Vancouver with another Aboriginal artist who was studying at Concordia. When I got to Montreal, I entered the same MFA program.”

After graduating from Concordia, Arthur moved to Ottawa and worked as a curator at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, and then moved to Toronto, where he established his art practice.

The Haisla village of Kitamaat, to which he returns every summer, continues to play a central role in Arthur’s identity and art. “Kitamaat will always be my home. I’m a bit of a nomad, but I will probably be buried there. Even though I live in Toronto, I keep in touch with the politics and land claims that are ongoing. A lot of my work is still based within my identity as a Haisla person. Whenever I give a lecture, I introduce myself as Haisla to give context. Kitamaat plays a huge role in how people perceive my work and how I explain it.”

Arthur began creating art inspired by being Haisla in the late eighties, when Aboriginal art in Canada emerged as a force. An example of this emergence was the 1989 exhibition, Beyond History, which took place at the Vancouver Art Gallery. It featured mixed media works by important Aboriginal artists like Carl Beam, Jane Ash Poitras and Joan Cardinal Schubert.

Seeing art that was readily identifiable as Aboriginal made Arthur realize that his own work had a place, although at the time, it did not entirely fit in: “Indian identity was really blatant in [the work presented in Beyond History], unlike mine. A lot of my photography was landscape-based. Some people thought photography was not art, and that my art was not Aboriginal because I did not photograph Indians. I have continued to photograph landscapes, but I also began to do sculptural work incorporating totems. I began to make work about my community, even though I was in Montreal or Toronto.”

An early example of art about Kitamaat is Arthur’s 1993 photograph, My Grandfather’s Shoes, also part of the National Gallery of Canada’s permanent collection. The photograph shows land near Kitamaat, cleared in anticipation of a residential development that never took place. In it, Arthur wears his deceased grandfather’s shoes, which were passed on to his family in a spiritual ceremony intended to continue the circle of life and to emphasize each member’s responsibility to the other. An eagle, dislodged from its nest in the clear cut soars above, in the upper reaches of the photograph, searching for its home.

His 2002 exhibit, stately monuments, reflects on Kitamaat, the Haisla village, and Kitimat, the post-war company town, built by Alcan to house the aluminum smelter’s workers. These two communities face each other across the Douglas Channel. Using black and white photography, cedar, aluminum, copper and traditional Northwest Coast crafts, Arthur’s totemic images explore these two communities, which are opposites in so many ways.

Kitimat, the creation of Alcan, has no history prior to 1950, and no roots in the Haisla territory that it occupies. Kitamaat, the Haisla Nation’s ancestral home, has a history stretching back thousands of years. stately monuments reflects on both places, exploring of the impact of colonialism on the artist, the Haisla people and the land occupied by the smelter and company town.

In his 2004 series, Delegates: Chiefs of Earth and Sky, Arthur’s art turns outward, and studies South Dakota through beautiful black and white photographs of the land where the Fort Laramie Treaty negotiations took place from 1885-1890. Warriors such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse signed this treaty, which promised their people land rights. Once gold was discovered in the Black Hills of South Dakota, the treaty was broken.

Each photo is mounted on a sheet of aluminum that resembles the sky. Punctuation marks are cut through each sheet. “The punctuation marks are the spaces in between the words, the silences in between. They symbolize the language used in the treaty — English — a language the Lakota couldn’t understand or read, yet they were expected to sign it. I named each artwork after one of the warriors, using their traditional Lakota names.”

Alongside Arthur’s evolving landscape photography, is the new theme of portraits in the form of his ongoing Mask series. The series was inspired by the mask carvings of Burton Amos, Arthur’s older brother. “My brother’s masks made me realize that I wanted to do huge portraits of Aboriginal people. These portraits, along with my other work, have extended the boundaries of my community to a more international platform.”

Through recent work like Delegates and Mask, Arthur Renwick’s art has taken on subjects that may seem far removed from the Haisla village of Kitamaat, the central theme in stately monuments and other, earlier exhibits. But appearances can be deceiving. Home and homeland remain the driving force behind Arthur’s work, regardless of how far he may travel, geographically or artistically.

“People of European ancestry often have a psychological homeland back in Europe that gives them a sense of their identity. For First Nations, that homeland is right here. We don’t have another place to go back to. This is it.”

Jennifer Dales is a writer living in Ottawa. She has reviewed art, poetry and non-fiction for the Canadian Medical Association Journal, Arc: Canada’s National Poetry Magazine and The Danforth Review. Her poetry has appeared in several journals, including Prairie Fire. She teaches in the professional writing program at Algonquin College. Her interest in First Nations art, literature and politics spans more than 20 years.

Upcoming showings of Arthur Renwick’s art:

• September: Unmasking at Canadian Culture Paris, (Canadian Embassy) and at Musée du Quai Branly. Group show with Adrian Stimson and Jeff Thomas.

• October: Group show in Montreal, with Concordia University. Fundraiser.

• November (or January): Solo show of new work, tentatively called MASK: Curators and Artists. In Toronto at Leo Kamen Art Gallery.

• March (or August): Group show in two parts called Hide. Part 1 opens in March 2010, and Part 2 opens in August 2010. In New York City at the Smithsonian Institute (National Museum of the American Indian).