Harold Innis wrote the history of Canada around its succession of staple exports, first to Europe and then to the U.S. He then wrote the history of empires and civilizations around the succession of media of communications. One of the bridges between these two phases of his work was the study of newsprint as a Canadian staple which supplied the input for the American press, with its vast consequences for public opinion and human consciousness.

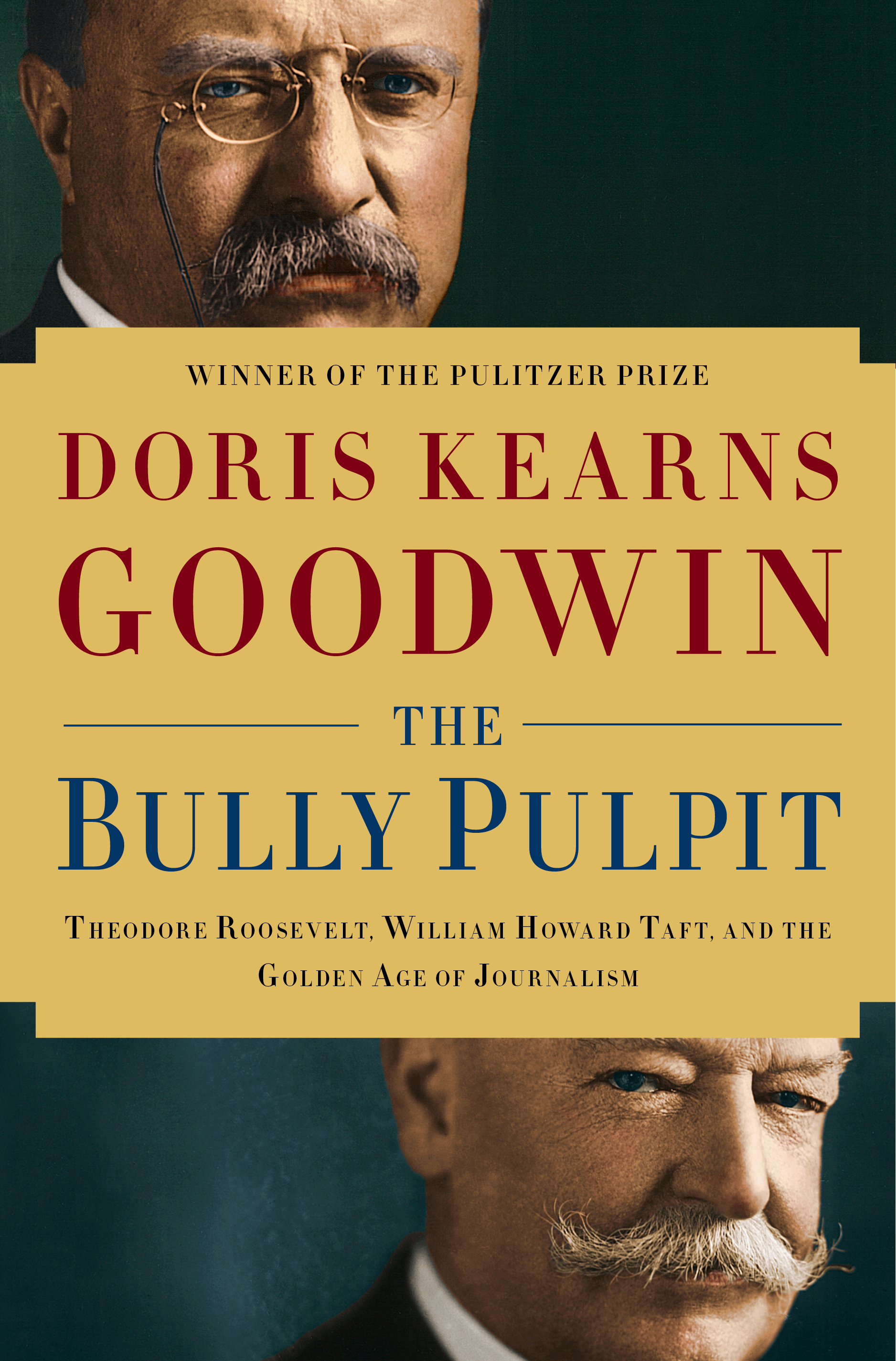

The best-selling American historian Doris Kearns Goodwin has made a signal contribution to this way of thinking in her most recent book The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft and the Golden Age of Journalism. Much has been written about the role of print journalism in spreading Roosevelt’s utterances — and also of the role of the sensationalist press in fomenting the Spanish-American War of that time. While the present view of historians on the latter is that it has been exaggerated, it certainly helped to create the Roosevelt persona. Kearns thoroughly documents the symbiotic relationship between Roosevelt and the journalists, and how the failure of Taft as Roosevelt’s successor to bond with the journalists undermined the effectiveness of his presidency.

What Goodwin focuses on is not the sensationalist newspapers so disliked by the bookish, including Innis, but on the magazines that sprung up in the early 20th century because of technological changes, notably in photoengraving, the desire of advertisers promoting brands for more and better space in this first Gilded Age, and the increasing availability of cheap paper from Canada. In differentiation from the newspapers, the magazines facilitated the rise of investigative journalism, of the muckraking exposing the need for regulation of the burgeoning corporation, for trust busting, for health and safety standards, for ending the pervasive corruption of politics.

This journalism fed the progressive politics of farmers and workers in the face of increasing corporate power. Famously, Ida Tarbell wrote the magazine series that became the book that tore the veil off Rockefeller and culminated in the break-up of Standard Oil.

As Innis — and McLuhan — insisted in their pioneering studies, media matter and each in its own way.

As with everything by Goodwin, the story is well told (including the fascinating relationship between Roosevelt and Taft which is central to her book but not to this blog), and in this case the message is distinctly progressive. It could restore one’s faith in the mainstream media, at least some medium at some time.