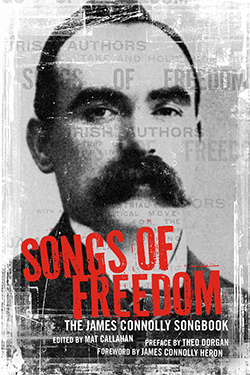

PM Press has just released Songs of Freedom: The James Connolly Song Book, edited by Mat Callahan, with an introduction by Theo Dorgan and foreward by James Connolly Heron.

Connolly, was an Irish revolutionary leader executed for his role in the Easter Uprising of 1916. He was also a passionate lyricist, penning numerous revolutionary songs as well as popularizing others. While his memory and work are retained in the collective consciousness in certain quarters — not the least being Ireland — much of this body of work has been diffused if not up to now, lost outright.

The singer-songwriter Mat Callahan has recently completed a project bringing this work together into a single volume with an accompanying music CD. Aaron Leonard recently corresponded with him via e-mail to ask about the project.

In his introduction, the poet and writer Theo Dorgan writes, “The trouble with Connolly in our time is he has become a hollow icon, a kind of ancestor figure to the Left, of no real substance to many who invoke his name save as a touchstone of legitimacy in a certain kind of politics.” Who was James Connolly?

[Dorgan] is writing from an Irish perspective in which Connolly’s role is harder to ignore than it might be elsewhere. And [Dorgan] is undoubtedly right since Connolly’s character, his incorruptibility and exemplary courage make him somewhat of an “impossible ideal” in today’s toxic political landscape. Venality and betrayal so dominate the scene that Connolly has either to be written out of history altogether or he must be made a saint to whom one can confess one’s sins while continuing to commit them.

Fortunately, we have Connolly’s own writings to judge his merits by [and] it is the accuracy of Connolly’s analysis and the clarity of his argument that make him important historically [and as a figure] of current and future struggles for human liberation.

Connolly was a revolutionary because reform meant surrender to perpetual servitude. He was a socialist because the private appropriation of wealth meant the immiseration of the people who in fact produce that wealth. And he was an internationalist because nationalism pitted worker against worker, a situation he saw first hand in Ireland and with even greater force on his visit to America.

Connolly was brilliant, without a doubt. Born into dire poverty in Edinburgh, self-educated, but becoming an important scholar and political theorist. Connolly was also steeped in the lessons of concrete struggles to organize the workers of Scotland, England and later on, Ireland and the U.S.

A student of Karl Marx, Connolly went on to creatively analyze the situation Ireland found itself in and to articulate positions regarding national liberation that were prescient, foretelling to a large extent, the great wave of independence movements that swept the world following WWII.

As the introduction notes some of the lyrics contain a “fluffy sentimentality” stamped by the period, yet the sentiment is sound and there remains a core vitality. For example, the “Rebel Song” is pretty direct, when he talks about “A song of love and hate,” but the line that grabbed my attention was where he writes that the hands of greed are, “Stretched to rob the living and the dead.” It sounds like he understood something about how capitalism operates.

What informed his writing and how did he see the role of song, compared to how we see it today?

Connolly was inspired by his involvement with the IWW [Industrial Workers of the World]. The use of songs had become a mainstay of labor organizing in the multinational-multilingual U.S. working class. Linguistic divisions could be overcome by music; solidarity and a fighting spirit could be encouraged by people singing together.

Connolly produced the original Songs of Freedom while in New York, in 1907 [and] it is from this song book that Connolly’s most famous pronouncement regarding music was drawn, the essence of which was, no revolutionary movement worthy of the name can be without its poetic expression. Without joyous, defiant singing it is the dogma of the few and not the faith of the many.

How did you get involved in this project and how did you end up uncovering and compiling all this material?

The short version is I wanted to celebrate my 60th birthday by singing revolutionary songs. I also had a bunch of Irish friends and fond memories of James Connolly from my youth. My stepfather held Connolly in high regard, impressing upon me the importance of Connolly’s ideas.

So, I set out to find Songs of Freedom only to be told by a bookseller in County Mayo that I wasn’t going to find it. He was the first to explain that the only existing copy was in Ireland’s National Library. So, I purchased the next best thing, which was the James Connolly Songbook published by the Cork Workers’ Club in 1972 and reprinted in 1980. The texts in this collection were what we based the bulk of the program on.

There are literally thousands of Irish revolutionary songs, but [we] felt it crucial to focus on Connolly. This was partly because we didn’t want to pander to nostalgic longings for an Ireland that never was and partly because under current circumstances Connolly’s diagnosis and cure for what ails Ireland are all too timely.

What kind of reaction are you getting to the book, both in Ireland and other places?

So far, overwhelmingly positive. Whatever one may think of Connolly’s ideas, the fact that the contents of this book are of great archival value and have been virtually unavailable for a century is significant. Even if one’s interest is confined to Irish or Labor history, or perhaps, popular song in political movements, there is crucial material here that would otherwise be difficult to obtain.

The real test, though, will be how young people receive this. Though the song book is historically significant in its own right, the urgent need for new generations to unearth Connolly’s ideas and grapple with them is even greater. It’s too soon to say but I’m optimistic that such interest will be ignited.

Why did you chose to include “A Rebel Song” and “Shake Your Banners” on the CD and what were the challenges in translating them?

We had to consider different problems when choosing the songs. One was time constraint [and the other] of musical and thematic variety. A third was how to make the songs “singable” by people today –especially those who had never heard of Connolly.

There are 19 songs by Connolly in the James Connolly Songbook. We narrowed it down to 13 songs, eight by Connolly, three about Connolly and one, “The Red Flag,” that was by Jim Connell and was in the original Songs of Freedom.

We had the problem of choosing from among lyrics that had similar themes. Looking for the broadest possible subject matter meant choosing not to do certain songs because they [were repetitious]. But “A Rebel Song” I knew to be one of Connolly’s first and best known lyrics. “Shake Out Your Banners,” was just a catchy, rousing title that got me started on some music.

We are a long way from 1902; there is no revolutionary worker’s movement, the notion of a socialist society let alone communism is scorned if not ignored entirely, and even the most radical forces today argue for an “anti-capitalism” that too often means radical reformism rather than an elimination of the whole mess of systematic surplus value accumulation.

In other words there seems to be no alternative that breaks with the dominant one. So what does James Connolly have to teach us in 2013?

Actually, Connolly faced no less daunting obstacles than those we face today. He was on the fringes of the socialist movement worldwide due to his advocacy of a revolutionary alternative to imperialist war.

Furthermore, the analysis that led him to launch the Easter Rising — which was doomed from the start — was visionary and little understood at the time or since. Connolly was among the few who realized that the British Empire could only be effectively challenged when it was preoccupied with inter-imperialist war. [He] was convinced it was in the interests of the great cause of human emancipation that an attempt be made even if it were to fail.

I am convinced he was right. Furthermore, I am convinced that anyone who reads the programme of the Irish Socialist Republican Party of 1896 [which is excerpted in the introduction] will see the practical solutions to Ireland’s current problems. From the abolition of private banks to free universal education through the college level, there are concrete policies that would go a long way to improving the lives of the common Irish person today.

Even more important is that Connolly combined a scholars’ dedication to history’s dynamics with the ability to communicate clearly to working people. His quest for truth did not make him an isolated, ivory-tower academic. He wrote powerfully, but he also brought these writings directly to the workers — a lesson that we certainly can learn from today.

Connolly’s vision of the future, while certainly incomplete, was nonetheless inspiring. In the nobility of its aims it captured the potential residing in human beings and in our struggle. Connolly grasped a truth amidst the ruins of centuries of resistance, rebellion and revolution.

Human emancipation is possible but it is made so, in part, by our ability to envision a better world. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously raise fundamental issues of equality, justice and human solidarity as a measure of our own actions and those of people claiming to represent us.

Holding everyone to these standards it not only a moral question but one of great practical import in evaluating what course to take at any given time. This is what Connolly has to teach us today.

Mat Callahan is a musician and author originally from San Francisco, where he founded Komotion International. He is the author of three books, Sex, Death & the Angry Young Man, Testimony, and The Trouble With Music. He currently resides in Bern, Switzerland.