When I began delving into the voluminous literature on the First World War, including the most recent, I repeatedly encountered an unfamiliar name: Stefan Zweig. I went to the movies last year to see the just released The Grand Budapest Hotel, a marvelous and magical film about lost times and, lo and behold, the first of the credits was to Stefan Zweig for inspiring it.

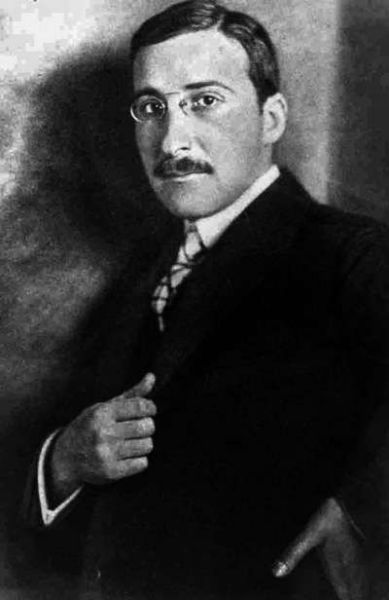

Zweig, born in 1881 in Vienna, in its heyday as capital of the Habsburg Empire, became one of the best known and most translated writers of his time, read throughout Europe, but not well known in North America. He was a prolific writer, of novels, plays, biographies, and of his final testament, his autobiography in the rich context of his time and place, with the revelatory title The World of Yesterday (from which the quotes below are taken.)

He was the cultured son of a wealthy Jewish industrialist. He led a life of privilege with, he insisted, no personal experience of anti-Semitism, and with no interest in politics. In a continent of rampant militaristic nationalisms he saw himself as a man of Europe, ahead of his times. For Zweig it was the best of worlds, a world where he felt secure, and he imagined it could last forever.

Then came the Great War, with Austria-Hungary, allied with Germany, fighting Britain, France, and Russia. Zweig, in his thirties and already a well established writer, did his military service as an officer, attached to the War Archives, documenting what was happening at the front. He never fought himself, refusing even to carry a rifle. He swore an oath to himself “never to write a single word that affirmed war or disparaged another nation,” and he honoured that oath for the rest of his life. He became a pacifist and remained so. Even in the midst of the war, he penned an anti-war play, Jeremiah, “the man of futile warnings.” He thought that the ordinary people he met “understood the war more truly than our university professors and poets.” He became increasingly a proponent of a united Europe.

In due course, Zweig was to see the First World War, as many still do, as the great dividing line between the good times — the long nineteenth century of progress — and catastrophe. An intellectual, a person of ideas, he saw the First World War as having nothing to do with ideas, whereas the intellectuals everywhere were mostly “indifferently passive,” seized by the optimism that was the conventional wisdom of the time and by the “blind belief that reason would balk the madness at the last minute.” He writes of “the terrible hatred which has penetrated the arteries of our time as a poisonous residue of the First World War.” It was his lot to experience this, to absorb it into his being. Europe’s crisis was his existential crisis. His senses heightened by war, when he visited Italy in the early 1920s, he smelled the vile fascism in the air that propelled Mussolini to power in 1922.

At the outset of the interwar years, Zweig prospered as his reputation as a writer grew. But the security of the past, which Zweig thought necessary to a writer, was lost. With the Hapsburg monarchy on the losing side of the war and the Austro-Hungarian empire dismantled, the ground under Zweig shifted. His Vienna was no longer a great imperial city but was rather the “provincial” capital of a minor country; Zweig moved to Salzburg. (Today’s left sheds no tears over the end of empire, but as empires go, the long lasting Austro-Hungarian was relatively benign, surprisingly multicultural, and with no extra-European colonies. Moreover, in the years before the war, the empire was industrializing rapidly and its economy growing apace.)

However, the worst was yet to come, for Austria and for Europe. With the rise of Hitler, Zweig’s world ended. He went into exile, first to Britain, then to America, and finally to Brazil. “I belong nowhere,” he writes, “and everywhere am a stranger, a guest at best.” Others went into exile, and sank new roots. Zweig was unable to do the same. He committed suicide with his second wife in 1942 at age 61, one day after completing the manuscript of The World of Yesterday. We still need his pacifist voice.

To have inspired a film as good as The Grand Budapest Hotel is to enrich and extend Zweig’s legacy. Let his name live among us.