The Otto Dix exhibition at the Neue Galerie, New York, comes to Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts on September 24. Ça vaut la visite. Rouge Cabaret: Love, Death, the Terrifying and Beautiful World of Otto Dix is the first one-man exhibition of his work ever held in North America.

It comes at a time when many of us are fearful of the new autocracy found today in our home and native land, at a time when unreported crime is rampaging unchecked, while the military want more money and youth thrown into Afghanistan.

Dix, one of the many great artists labelled Degenerate by the Nazis, said he wanted “to show life without dilution.” Nothing pretty-pretty for him. After three years in the trenches in The First World War as leader of a machine gun squad, Dix knew life and death, despots, autocracy. He knew war.

In 1945, in the final days of The Second World War, Dix, then aged 55, was drafted once again, taken prisoner by the French, and spent a year in captivity. What did he think of while in prison? He knew war was no natural disaster. He and his fellow artists, the so-called Degenerates, knew about Being Human.

Ibsen said it is the role of the artist to see, and to see more clearly than anyone else. Dix, along with clear-sighted citizens, artists, writers, and musicians of his time, paid a high price for this vision. Maybe that’s why his work is still devastating today, even more so, because today’s viewers have the luxury of hindsight.

In 2010, we can look with shock and awe at his drawings of war, Der Krieg, 50 etchings of WWI, which were published 1924. They are “rivalled only by Goya’s Desastres de la guerra as an artistic statement of the true nature of war,” says the exhibition. Dix’s drawings, as powerful as Goya’s, show gruesome scenes of combat and devastation: the wounded, battle-weary troops, a village being bombed, prostitutes, mud, skeletal trees, skulls, and worms, as well as the desperate fun of the doomed, the dance hall at the brink of death.

Dix’s great artistic statement of the true nature of war could do nothing to modify the human brain that he drew so well in pen and ink. W.H. Auden says poetry makes nothing happen. Nor do art and music as the exhibition shows. No art could prevent Spain, WWII, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Congo, Sudan, Rwanda, and more. So why do certain politicians fear artists, satirists, clarity of vision?

Life in Berlin after the First World War was humming and hyper. Dix continued painting amidst the sex, drugs and cabaret. His work exploded in strength, power and social awareness.

His portrait of the dancer Anita Berber (1925) shows a woman in scarlet, self-destructive desperation. She died of a drug overdose in Berlin before she was 30. Dix and his wife loved her.

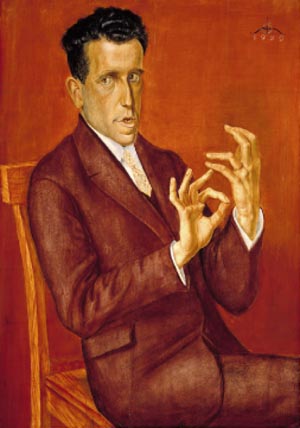

In 1926, the art critic Paul Ferdinand Schmidt wrote: “Dix comes along like a natural disaster: outrageous, inexplicably devastating, like the explosion of a volcano.” This explosion is evident in portraits like the AGO’s Dr. Heinrich Stadelmann; Montreal’s Dr. Hugo Simons; even a grinning, demonic self-portrait in black chalk, where he looks a little like a rather grotesque young Auden. And whose private collection, I could not help wondering, has the watercolour, Dedicated to Sadists, painted in 1922?

In 1933, Dix was removed from his professorship in Dresden. Maybe Hitler did not like being depicted as Envy in Dix’s painting Seven Deadly Sins. When the Nazis came to power, they were swift in removing all the so-called Degenerates, anyone who opposed them, in fact. Totalitarians, as we know, never appreciate clear-sightedness.

Also at the exhibition visitors can hear poignant recordings of many musicians considered decadent by the Nazis.

In Canada, Stephen Harper’s view that: “Ordinary people don’t care about the arts,” could be similar to the ordinary people in Bavaria who welcomed Hitler, the ordinary people who follow Fox News, and the ordinary people cheering the Koch-funded Tea Party.

But while some ordinary people are attracted to reactionary forces, abusive control freaks, and repressive bullies, others, like me, value freedom and progress, transcendent art, and liberated thinking. The exhibition at the Neue Galerie was, happily, very well-attended by many ordinary, but even elegant people.

Serge Sabarsky, a co-founder of the Neue Galerie in New York, loved Dix’s work. He owned many of the works seen in the exhibition. He wrote: “Dix was able to represent the banality of life, the unadorned face of humanity as no one else can.”

As a Jew, Sabarsky himself experienced writer Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil” in the Third Reich. The Gestapo came for him in 1938. Somehow he made it to New York. Now we can view his Otto Dix works in this splendid exhibition with its many layers, insight, humour, wit, intelligence, and searing honesty.

While at the New York show I visited the gallery bookstore, where I bought The Drinker, by German writer Hans Fallada, a tale of a self-absorbed, self-destructive, self-pitying, self-justifying addict. Fallada, the son of a respected judge, was considered politically unreliable by the Nazis, and emotionally disturbed by his family and friends.

Fallada’s insight though, described in the 1930s by poet Kurt Tucholsky, as “so uncannily genuine it gives you the shivers,” can still make you shiver with its clear-sighted, unnerving look at human behaviour and aspects of German life at that time. Fallada, a man of unfortunate addictive habits, never did manage to write propaganda for the Nazis as they hoped, but he did manage a clarity of vision that speaks to us today.

John Willett writes in his Afterword to The Drinker that “bleeding reality becomes material for the imagination.” Dix and his fellow painters knew firsthand about bleeding reality. So did Fallada and his friends. Some of these friends were executed by the régime.

The new alliance of Conservatives in Ottawa is busy cutting arts funding and cultural initiatives. They do not welcome clear-sightedness. They hope to change the ideological face of Canada. They may have momentary success. When big media own everything and only certain voices get heard, propaganda works, Every ideologue knows that… but for how long?

Otto Dix, Kurt Tucholsky and Hans Fallada are just three of the great minds despised by the Nazis, minds that gave us words, music, images and ideas that will resonate for as long as exhibitions are possible, as long books are printed or kindled, as long as the human spirit, perception, and imagination triumph over repression, torture, totalitarian control and despair. Poetry may make nothing happen, but it hangs in there.

Otto Dix died in 1969. Hans Fallada died in 1947.

Writer Margaret van Dijk grew up in New Zealand and is now based in Toronto. She is looking forward to the Toronto International Film Festival and wonders if movies with a circus theme about political conflict and war will make her Degenerate.