As a mixed-race woman of Black heritage, I have always connected deeply to Shakespeare’s Othello. For people of colour growing up in a predominantly white nation with a deeply Eurocentric curriculum, non-white characters like Othello are significant because they affirm our existence in literature, and help us articulate our struggles with internalized racism and white supremacy.

There are so few instances in Western literature where Black characters are permitted to exist, let alone to exist as multifaceted, sympathetic, and central. Othello is one of the rare texts in the English literary canon to make a Black character its protagonist and to focus on issues of anti-Black racism.

For these reasons, the choice by a major theatre troupe at Queen’s University, Queen’s Vagabond, to cast a white woman in the role of Othello sparked outrage and hurt for students of colour.

To take the one Shakespeare play that is explicitly centered on a Black man, whose experience of anti-Black racism at the hands of his compatriots is instrumental to his demise, and give the role to a white girl tells students of colour that even in rare roles specifically crafted for them, there is no space for them.

Although Vagabond’s artistic directors cancelled the production after receiving numerous letters of complaint, they failed to accept responsibility for their mistake.

Announcing the show’s cancellation the directors stated that the production had become “unsafe for the members involved, as many have been personally approached and have felt attacked.”

Queen’s Vagabond claimed that they were aware of the social implications of Othello, but that their “artistic choices were all made with reason and informed intention.” They bemoaned the backlash against their choices, stating that “when [the dialogue] becomes invasive and mean, it diminishes any form of creative expression.”

This initial post only served to intensify the feelings of alienation and degradation experienced by students of colour, and Black students in particular. Rather than acknowledge the anti-Blackness and erasure in their choice to cast Othello as a white woman, the directors centred the conversation around their hurt feelings at having their “artistic choices” challenged.

While Vagabond’s artistic directors did release a second statement in which they apologised “to anyone who has felt displaced, belittled, or any other negative emotion due to actions that we have taken,” their apology was undermined by their contribution to a National Post article where they appealed to past examples of whitewashed Othello as justification for their choice, citing a 2011 production in Germany which “encountered little opposition” for casting a white woman as Othello. The article asserts that “for centuries [Othello] was performed by white actors in Blackface” but also fails to mention the 2011 production had Othello played by an actress in a gorilla costume.

Othello’s Blackness and humanity are non-negotiable, and instances of racism perpetuated in previous casting choices do not justify continuing to perpetuate them now. Casting a white person as Othello, and decontextualizing his oppression has always been erasure; putting an actor in Blackface or literally dehumanizing Othello by representing him as an animal has always been racist.

One of the directors is quoted in the National Post interview saying “race is what makes [Othello] an outsider, and he’s vulnerable because he’s an outsider. He’s not upset because of his race; he’s upset because he’s different.” This statement runs blatantly counter to every aspect of Othello’s narrative.

Othello is explicitly degraded for his race: in an effort to prevent Othello from marrying the white Venetian Desdemona, the villain Iago awakens Desdemona’s father with the shout “Even now…an old Black ram / Is tupping your white ewe.”

It is Othello’s positionality as a Black man, surrounded by white people who perceive him as innately less human, that brings about his tragedy; the unyielding, insidious, pervasive nature of white supremacy claws its way into his heart and fills him with doubt. He is brought to ruin by Iago because it is far too easy for him to believe that no one, not even his beloved wife Desdemona, can truly respect or love him. To make Othello white denies the very essence of his story.

Despite the emotional toll, this incident has given students of colour the space to speak out about the racism they have encountered at Queen’s. In the last few days, many students of colour involved with the drama department have spoken about the marginalization they have experienced at the hands of their peers, and the ways in which they have been made to feel inferior for their race.

In the broader context of the university, students and professors of colour alike have talked about facing systemic and interpersonal barriers in their work and lives here. Queen’s is disproportionately white, and not enough is being done to ensure the wellbeing and access to opportunity for people of colour at this institution.

We cannot be expected to remain silent about racism out of fear of being perceived as aggressive. We cannot ignore our experiences just to appease and comfort white members of this community.

Evelyna Ekoko-Kay is a Hamilton-born writer and activist. Currently, she is attending Queen’s University as a fourth-year English major, with a focus on postcolonial literature.

Like this article? Please chip in to keep stories like these coming.

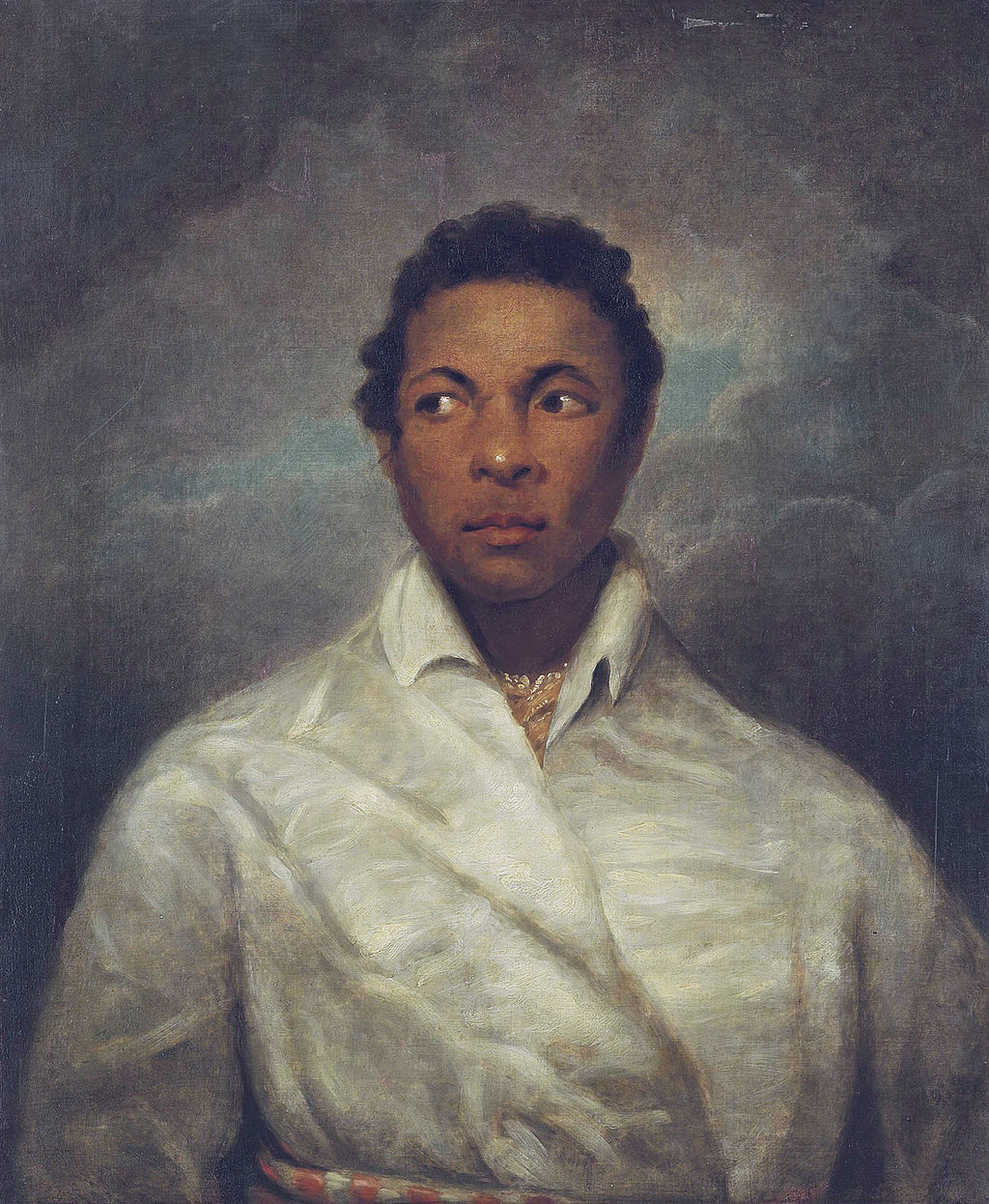

Image: Ira Aldridge/Wikimedia Commons