A recent article, “Would a united left really be able to topple Tories?” by pollmeister extraordinaire Éric Grenier of Threehundredeight.com — which draws, in turn, upon a recent poll by Angus-Reid Public Opinion — provides fresh fodder for political thought. The Angus Reid poll found that, of decided Canadian voters, 50 per cent said they would vote for a joint NDP or Liberal candidate. This compares to 39 per cent who would vote Conservative and 11 per cent who would vote for a Green, BQ or other candidate. This is true across the country in every province and territory save Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. These results closely mirror the percentages of support the respective parties received in the 2011 federal election leading Grenier to conclude that, “if the parties decided to co-operate they would lose very few votes.”

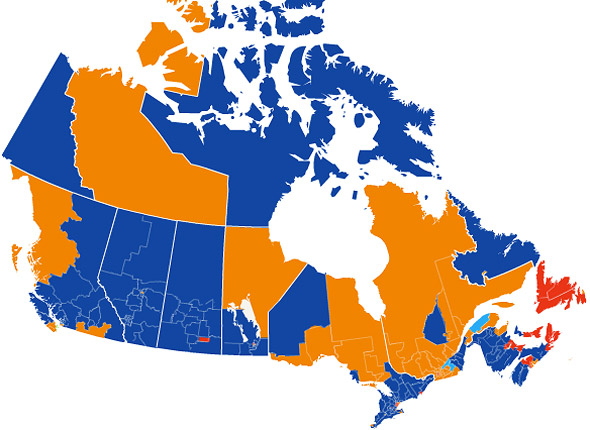

Grenier projects that an election based on the results of this polling would result in the election of 122 Conservatives, 118 New Democrats, 67 Liberals, and one Green. This would result in either a very narrow Conservative minority government, or (potentially) a stable NDP-Liberal coalition government with 185 seats. Grenier’s analysis based on this polling data rather closely mirrors my analysis in The case for NDP, Liberal, Green co-operation conducted for Project Democracy in February, 2012 which is based on the 2011 election and second party support.

In determining the results of NDP-Liberal co-operation one cannot simply assume that all the support of both parties would accrue to a joint candidate (1 + 1 = 2). In such circumstances some supporters would rather vote for a Conservative candidate, or would simply not vote at all. Fortunately, such detailed information is available as a result of polling conducted by Ekos Research prior to the last election. It shows:

“That 13.5% of NDP supporters would cast their ballot for the Conservative party if no NDP candidate was available; 37.7 per cent would support the Liberals, 19 per cent the Green party, and 17.4 per cent have no second choice (i.e., they would not vote for any other party). For Liberal supporters, 12.6 per cent would vote for the Conservatives, 54.1 per cent the NDP, 12.0 percent the Green party, and 17.1 per cent have no second choice. Finally, 11 per cent of Green supporters would support the Conservatives, 40.3 percent the NDP, 17.4 per cent the Liberals, and 27.4 per cent have no second choice.”

Employing riding-by-riding results from the 2011 election, and factoring in these second-choice preferences as determined by Ekos Research, my riding-by-riding projections are that the Conservatives would win 126 seats, the New Democrats 114, the Liberals 63, the BQ 4, and the Greens 1. Again, the political result of this would be either a very narrow Conservative minority government, or (potentially) a stable NDP-Liberal-Green coalition government with 178 seats.

Important notes: these analyses are not intended as exercises in alternate history, but rather to shed light on what political co-operation — not mergers — between progressive parties could yield in the next election. Also, as a result of seat redistribution introduced by the Conservatives in 2011, in the 2015 election there will be 338 electoral ridings rather than 308 as is presently the case.

Grenier asks a second question, namely would a combined NDP and Liberal candidacy bleed votes in the same way that the newly united Conservative party, which received 30 per cent of the vote in the 2004 election, lost votes compared with the sum of the Canadian Alliance and Progressive Conservative support, which in the 2000 election received a combined total of 38 per cent of the vote. After examining both situations Grenier concludes that, “It is extremely unlikely that the Liberals and NDP would lose votes in exactly the same way as the Tories did in 2004.” I think Grenier is correct, however, a precise empirical answer to his question was already provided by the 2011 Ekos Research polling data.

Why fear a winning formula?

Thus, two independent analyses, conducted with different methodologies and based on different sets of data, independently project NDP-Liberal co-operation could lead to a stable majority coalition government. Although the specific platform of such a coalition would need to be determined, is there anyone in the approximately 65 per cent of Canadians who currently oppose the Harper Conservatives who doubts that such a governing coalition would produce dramatically better governance than the present federal government? Anyone …? I thought not. Even a simple catalogue of the egregious blunders, flagrant stupidities, misguided notions, moronic programs, needless cutbacks, punitive measures, legislative abominations, abuses of process, philistine measures, Orwellian newspeak, bald-faced duplicity, and the sheer, boundless, all-embracing idiocy of the Conservative government would doubtless exceed the 452 pages of the notorious omnibus budget implementation bill (C-38).

Consequently, given that political co-operation is without question a key to political power — and that all politicians of all stripes pay homage to the notion parliamentary political co-operation for the greater good of the Canadian citizenry — why is there such an allergy on the part of politicians to actually doing it? When better governance that would serve the interests of a large majority of Canadians could be achieved, why is progressive Canadian politics mired in a zero-sum rut? If co-operation is considered a virtue for political parties after an election, why is it considered a vice prior to one?

Since 2008 when Project Democracy began (originally as Vote For the Environment) I’ve spoken with hundreds of politicians, partisans, pundits, and pollsters (the four “P’s”) of every political stripe. It appears to me that two factors are principally responsible.

The zero-sum game

There is a political culture in Canada that is deeply entrenched in, and married to, the zero-sum game — my loss is your gain and vice versa. In part, this is wholly understandable. Politics is about a contest of ideas and every party attempts to win adherents. The first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system further reinforces this with its ultra-simplistic formula of a “race” with one winner and everyone else losing. It’s a winner-take-all contest for whomever can eke across the finish line, even if they lack a plurality and are only microscopically ahead of the second-place contender. In this context, partisanship readily morphs into hyper-partisanship and despite the conspicuous failings of the zero-sum approach, and its consequent reverberations into the quality of governance, many of the four P’s are unable to conceive of a politics not conducted on this basis. This is a kind of political macular degeneration wherein peripheral matters remain in focus, but the central vision (the necessity of effective, democratic, representative government) has blurred beyond recognition.

Moreover, the entire enterprise morphs into a game, a contest to beat the adversary and come out on top. Legitimate policy ideas and objectives serve as the stimulus for the contest, but soon, like hounds after the fox, they are racing like madmen over the political landscape focused solely on the outcome of the contest.

Behind the reluctance to re-conceive the zero-sum game are some understandable hesitations. I’ve spoken with many politicians and partisans who have spent years in the political trenches, battling it out on the hustings, setting and defusing political IED’s, nursing wounds, the outcomes. They harbour deep suspicions and resentments and have the political scars to show for it. Convincing these political operatives to defuse tensions and build trust — when their natural instinct is to skewer the opponent — is a non-trivial undertaking.

Cold feet for hot reform

Electoral and political reform are the keys to political cooperation. There is no appetite for a merger amongst Green, Liberal, and NDP parties, nor would such a move serve democratic pluralism. A healthy democracy supports many strands of political thought and a healthy political system supports this multiplicity of views and provides a forum for them to constructively weave together. Thus, even stopgap political cooperation presupposes a common desire. Defeating the Harper Conservatives as a one-off can hardly be sufficient to surmount the pitfalls of co-operation if the object is simply to resume zero-sum game verbatim the next time round. This would be an unpalatable and pointless political exercise. The dangling carrot available through political co-operation needs to be some kind of electoral and political reform — beneficial to the parties, the citizenry, and Canadian democracy in general.

Both the New Democratic Party and the Green Party formally support electoral reform, and in particular, the introduction of proportional representation (PR). The position of the Liberal Party is non-specific and non-committal: “Liberals are committed to exploring Parliamentary and Electoral reform in order to realign our institutions with democratic principles and to ensure more meaningful and effective representation” but does at least commit to “exploring” electoral reform. However, if there was real appetite for electoral reform it would be immediately seized on by all parties concerned. The fact that it is not is (in my estimation) a clear indication that despite professed desires, much of the party nomenclatura remains “deeply tepid” about reform. Despite the manifold failings of FPTP whenever there are more than two political parties on the playing field (and the greater the number of parties, the more erratic, unpredictable, and unrepresentative are the results), the deep-seated zero-sum temptation is to go it alone, shoot for the moon, at last achieve the winning conditions, and attain majority rule. What vision could be more splendid?

The common excuse given as to why joint candidates or political co-operation is impossible is that not running a full slate of candidates is somehow “undemocratic.” It would deny party supporters in a riding the opportunity to democratically express their political convictions at the ballot box. This is a kind of clutching at political straws and ignores the vast democratic deficit that currently grips the country in which Parliament has been prorogued to evade a vote of confidence in the House of Commons, coalition governments have been derided as illegitimate, a sitting government has been found in contempt of Parliament, time allocation is routinely used to limit debate, information is not made available to parliamentarians and committees to allow them to adequately discharge their responsibilities, omnibus bills are used to circumvent parliamentary oversight of legislation, the results of referenda are ignored, there are allegations of electoral fraud, ministerial budgets have been perverted to fund projects not approved of by Parliament, and erroneous financial information (to the tune of $10 billion) has been provided to Parliament. One might suppose that any balanced consideration of the present democratic deficit would indicate that any measures to address it, whether via a one-time primary contest of the kind proposed by NDP House Leader Nathan Cullen when he was a leadership contender, or some other system, would be a top priority. However, the seemingly tremulous commitment to electoral and political reform appears to prevail.

Where do we go from here?

Seemingly nowhere. Despite:

1. Analyses such as Éric Grenier’s for Threehundredeight.com and my own for Project Democracy;

2. A LeadNow survey of almost 10,000 respondents this winter which found that 95 per cent (22 per cent agreed; 73 per cent strongly agreed) that NDP, Liberal, and Green parties should co-operate to defeat the Conservative government, introduce electoral reform and “… make sure our government better reflects the values and priorities of all Canadians”;

3. Pollster Frank Graves of Ekos Research who has argued (based on statistical analyses) that the only way to beat the Conservatives is for the NDP and Liberals to join political forces;

4. University of British Columbia political scientist Max Cameron whose position is that co-operation among opposition parties is an idea that shouldn’t and won’t go away despite Thomas Mulcair’s position; and

5. The 24.6 per cent of NDP members who supported the candidacy of Nathan Cullen, who campaigned strongly on this issue;

Political co-operation appears moribund. It takes at least two to tango and at the moment only Green Party leader Elizabeth May is standing on the dance floor. During his leadership bid, the NDP’s Thomas Mulcair was emphatic in ruling out political cooperation between the NDP and Liberals. A new Liberal leader will not be chosen until April 2013, and because of Mulcair’s unequivocal stance, it will be unlikely that anyone running for the Liberal leadership (a Liberal ‘Nathan Cullen’ as it were) will espouse a pro-co-operation position.

Although Grenier writes: “Recently, some NDP and Liberal riding associations across the country have mused that they are considering supporting a joint candidate between the two of them in the next federal election to consolidate support and improve the chances of that joint candidate defeating the riding’s Conservative candidate,” such co-operative initiatives appear to be confined to the riding level and are taking place in spite of party policy rather than because of it.

Recently political columnist Ralph Surette wrote, “[Stephen Harper’s] philosophy would be that of the Republican guru who delivered the famous line that the idea was to make government so small that you can “drown it in a bathtub.” After that’s done, corporations take over, elections are manipulated and the little guy gets even littler.”

One would hope that common political sense is not similarly being drowned in a bathtub of partisanship so that two thirds of the Canadian electorate are not disenfranchised for yet another term of Harper majority rule. Canadian society is already turning blue, starved of democratic oxygen; yet another four years of Harper rule would be sure to asphyxiate it.

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.