In the winter of 1975-76 I was living in the depths of the Zagros Mountains in Iran. I was working for the Persian Department of Environmental Conservation, based in a little village on the shores of Lake Parishan in Dasht-e Arjan National Park. Over the months I was there I traveled extensively in the western half of the country through the provinces of Khuzistan, Luristan, and Fars visiting staying in cities like Tehran, Esfahan, Shiraz, Dezful, Ahvaz, Abadan and many small towns and villages.

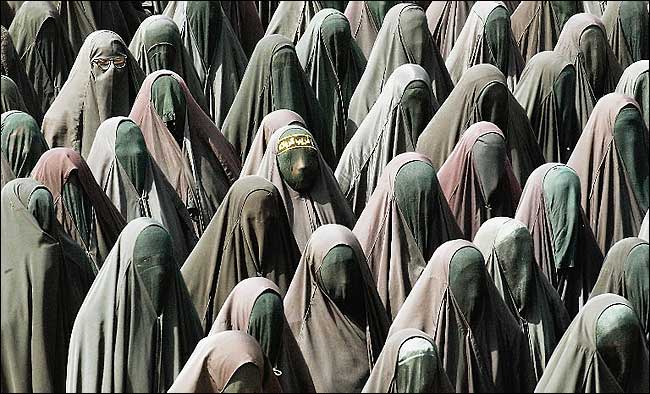

In my travels I met and talked with hundreds of Persians; educated upper-class elites, impoverished villagers, merchants, laborers, game wardens, Kurdish refugees, Bakhtiari tribes-people, marsh Arabs, village elders, farmers, students, biologists, and bureaucrats — almost all of them men. There was no way around it. This Islamic nation was, and is, a divided society — divided by gender. I drank tea and ate meals in countless small villages, gathered around glowing coals in mud-brick dwellings with village elders and townspeople — but the women gathered and ate separately in the back rooms. Although I was introduced to all the men at the gatherings, I at most caught fleeting glimpses of the women as they served food; no introductions, and certainly no discussions.

In my many conversations — which covered the full gamut of human existence, from Sufism to vegetarianism, from wildlife ecology to sex, from international politics to music — I learned and shared a great deal. I found the guys I spoke with to be as curious, funny, enthusiastic, and engaging as any others of my acquaintance, with one notable exception — they knew almost nothing about women. Not surprising considering that the only women most of them knew were their mothers and sisters, and even there the gender divide was apparent. They were incessantly curious about women, and as a westerner bombarded me with questions (Tell us about sex in America!) or even sought my advice about entering into arranged marriages. But their actual experiential knowledge of women as people — with ideas, dreams, aspirations, and passions — was amazingly slender.

In the towns and villages I encountered women from afar: sparkling jewels with their extraordinarily bright attire, gleaming jewelry, and brilliant eyes that vanished beneath their dark chadors when they stepped into the public realm.

Only in some of the cities — Shiraz and Tehran where I spent extended periods — did I actually get to meet women. In urban settings some women — mostly those young and educated — had enough personal and political freedom that they cast off not only their chadors, but also the traditional restrictions placed upon them. They were educated, had jobs and careers, had their own apartments and social lives, made decisions for themselves, not least of which was determining if, and when, and whom to marry. The few that I had an opportunity to meet were also as curious, funny, enthusiastic, and engaging as other women I had met in my travels. But for the most part there was a chasm as wide as the Persian Gulf between genders in much of Iran.

Only in some of the cities — Shiraz and Tehran where I spent extended periods — did I actually get to meet women. In urban settings some women — mostly those young and educated — had enough personal and political freedom that they cast off not only their chadors, but also the traditional restrictions placed upon them. They were educated, had jobs and careers, had their own apartments and social lives, made decisions for themselves, not least of which was determining if, and when, and whom to marry. The few that I had an opportunity to meet were also as curious, funny, enthusiastic, and engaging as other women I had met in my travels. But for the most part there was a chasm as wide as the Persian Gulf between genders in much of Iran.

These reflections are prompted by a recent commentary by Globe and Mail columnist Sheema Khan entitled Muslim men: Stop blaming women. Khan’s departure point, in turn, is an article by the New York Times Cairo correspondent Mona El-Naggar, The Female Factor; Extolling female subservience, and adding followers in Egypt, which takes aim at premarital classes being run by the Muslim Brotherhood. The message delivered in these classes is that “Women are erratic and emotional, and they make good wives and mothers — but never leaders or rulers.” Instructor Osama Abou Salama asks women, ”Can you, as a woman, take a decision and handle the consequences of your decision?” A number of women shake their heads even before Mr. Abou Salama answers: ”No. But men can. And God created us this way because a ship cannot have more than one captain. A woman takes pleasure in being a follower and finds ease in obeying a husband who loves her.”

As Khan points out, such emphatically patriarchal views about women are hardly new in the Islamic world. Gender equality (or it’s lack thereof) is a vast topic touching on education, marriage law and customs, property rights, employment opportunities, civil and individual rights, sexuality, dress codes, and religious practice, which in recent years has been the subject of many Islamic feminists. From honour killings and female genital mutilation (a.k.a. female ‘circumcision’), all the way to the inability of women to have jobs, go out unaccompanied, or drive cars, there are a host of oppressive and restrictive practices that women have been subjected to.

As Khan points out, such emphatically patriarchal views about women are hardly new in the Islamic world. Gender equality (or it’s lack thereof) is a vast topic touching on education, marriage law and customs, property rights, employment opportunities, civil and individual rights, sexuality, dress codes, and religious practice, which in recent years has been the subject of many Islamic feminists. From honour killings and female genital mutilation (a.k.a. female ‘circumcision’), all the way to the inability of women to have jobs, go out unaccompanied, or drive cars, there are a host of oppressive and restrictive practices that women have been subjected to.

Sheema Khan takes up this case, arguing that patriarchal and sexist views “must be challenged by Muslims, based on Islam and Islamic history.” Khan points out that: Mohammed worked for a woman (Khadija) for ten years, after which she proposed to him; authentic traditions reveal that Mohammed’s wives would often question him, including one interchange that precipitated the revelation of a Koranic verse about gender equality before God; a woman (Umm Sulaim), several months pregnant, fought alongside the Prophet during a battle. Another woman publicly challenged a proclamation of Omar, the second Caliph. Mohammed’s public response was: “The woman is right and Omar is wrong.”

While I understand this line of reasoning (finding a theological basis with which to refute what Khan calls the “irrationality, thy name is woman” paradigm), in my view this misses a critical point. The basis of a modern civil society is the recognition of essential human rights and equalities. That all people — irrespective of race, colour, belief, language, social status, age, and gender — are endowed with the same equal rights and entitled to the same opportunities. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is an encapsulation of this contemporary view of humanity. The change from a medieval to a modern society is reflected by humanist laws that underpin such rights, and not by reference to religious texts. Thus, as a society, we need to accept the social, political, civic, personal, and other equalities of women, and their rights to freely act upon them, because of the shared humanity of us all. It’s true that one can find texts in a variety of religious traditions that variously uphold such understandings (and other texts that do not) but in a modern society these cannot form the basis of civic rights, responsibilities, and conduct. And this is as true the rights of women as it is of many other social issues.

While I understand this line of reasoning (finding a theological basis with which to refute what Khan calls the “irrationality, thy name is woman” paradigm), in my view this misses a critical point. The basis of a modern civil society is the recognition of essential human rights and equalities. That all people — irrespective of race, colour, belief, language, social status, age, and gender — are endowed with the same equal rights and entitled to the same opportunities. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is an encapsulation of this contemporary view of humanity. The change from a medieval to a modern society is reflected by humanist laws that underpin such rights, and not by reference to religious texts. Thus, as a society, we need to accept the social, political, civic, personal, and other equalities of women, and their rights to freely act upon them, because of the shared humanity of us all. It’s true that one can find texts in a variety of religious traditions that variously uphold such understandings (and other texts that do not) but in a modern society these cannot form the basis of civic rights, responsibilities, and conduct. And this is as true the rights of women as it is of many other social issues.

Relicts of medieval thinking are certainly not confined to Muslim societies. One can readily find examples in the conduct and beliefs of Christian, Hebrew, Hindu, Buddhist, and other religious zealots — and not only in regard to the role of women in society. These need to be challenged not on the basis of religious texts and dogma, but on core humanist values as expressed by the Universal Declaration of Rights (UDHR). The challenge faced by women in Muslim countries is that most Muslim states are not signatories of the UDHR, having instead signed the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (CDHRI). While this is an important step beyond having no commitment to human rights, CDHRI has been subject to criticism for its affirmation of Islamic Shari’ah as its sole source (Article 24 states: “All the rights and freedoms stipulated in this Declaration are subject to the Islamic Shari’ah”). Thus, while forbidding discrimination on the basis of sex and affirming that women have a right to marriage, equal human dignity, their own rights to enjoy, duties to perform, rights to financial independence and to retain their names and lineages, CDHRI stops well short of affirming the fundamental equality of women.

In the months I spent in Iran I witnessed a society in which yin was emphatically separated from yang. My vantage was clearly that of a westerner, however, from that perspective it was clear to me that a healthy, balanced, and equitable society is best achieved by having healthy, balanced, and equitable relations between genders. The fewer the preconceptions, barriers, obstacles, and asymmetries between people, the fewer the opportunities, for misunderstandings, biases, tensions, and oppressive behaviour. I was appalled by the recent announcement that 36 Iranian universities have banned women from 77 degree programs in the country, an act of theologically motivated gender discrimination. In a letter to United Nations Women Executive Director, Michelle Bachelet, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi, herself a Persian, has called attention to the deteriorating women’s rights situation in Iran, not only in terms of education, but also access to birth control, and human and civil rights.

In the months I spent in Iran I witnessed a society in which yin was emphatically separated from yang. My vantage was clearly that of a westerner, however, from that perspective it was clear to me that a healthy, balanced, and equitable society is best achieved by having healthy, balanced, and equitable relations between genders. The fewer the preconceptions, barriers, obstacles, and asymmetries between people, the fewer the opportunities, for misunderstandings, biases, tensions, and oppressive behaviour. I was appalled by the recent announcement that 36 Iranian universities have banned women from 77 degree programs in the country, an act of theologically motivated gender discrimination. In a letter to United Nations Women Executive Director, Michelle Bachelet, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi, herself a Persian, has called attention to the deteriorating women’s rights situation in Iran, not only in terms of education, but also access to birth control, and human and civil rights.

In my view, until the status of women is based on civil rather than religious precepts and guarantees, the gender playing field will remain markedly uneven — and it will not be tilted in favour of women.

During my time in Iran I also witnessed the sharp dialectic between secular and religious visions of society (the subject of a future article). There are clear tensions between modernist and traditionalist forces in Persia, a country with a deep historical, architectural, musical, artistic, and cultural roots and many educated, talented, and forward-thinking people. These issues are currently at a particularly acute point with the spectre of a military attack looming over Iran, based on real or perceived fears that the Iranian government is developing nuclear weapons. On the basis of any analysis, a military action directed against Iran would greatly polarize internal political dynamics, potentially destabilize significant geopolitical equations, and would be a very significant setback in cultivating a modernist, secular society in the country. The collateral social and political damage — for women as well as men — would be enormous. We can, and must, aspire to better solutions.

During my time in Iran I also witnessed the sharp dialectic between secular and religious visions of society (the subject of a future article). There are clear tensions between modernist and traditionalist forces in Persia, a country with a deep historical, architectural, musical, artistic, and cultural roots and many educated, talented, and forward-thinking people. These issues are currently at a particularly acute point with the spectre of a military attack looming over Iran, based on real or perceived fears that the Iranian government is developing nuclear weapons. On the basis of any analysis, a military action directed against Iran would greatly polarize internal political dynamics, potentially destabilize significant geopolitical equations, and would be a very significant setback in cultivating a modernist, secular society in the country. The collateral social and political damage — for women as well as men — would be enormous. We can, and must, aspire to better solutions.

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.