Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a supporting member of rabble.ca.

Emma Pullman is a Vancouver-based researcher, writer and campaigner. She is a campaigner with for Leadnow.ca and campaigns consultant for SumOfUs. Emma will spend the next two weeks in Fort Chipewyan, Anzac, Fort McKay and Beaver Lake meeting with First Nations elders and local residents about the impact of the tar sands on their lands and communities. This series will recount her findings and reflections until her trip concludes when she joins Aboriginal communities from across Turtle Island in Fort McMurray for the Healing Walk against the tar sands on July 5-6. You can read about her journey here and in the Vancouver Observer.

I travelled to the territory of the Cree, Dene and Métis peoples of northern Alberta, to learn about the tar sands and their impacts on the land and its inhabitants.

It’s been 80 years since my grandfather worked here as a fur trader, yet today the land is still being colonized for profits that are shipped away — while the real costs are borne by the people and communities who have lived here all along.

A journal of life in Fort McMurray and Fort Chipewyan

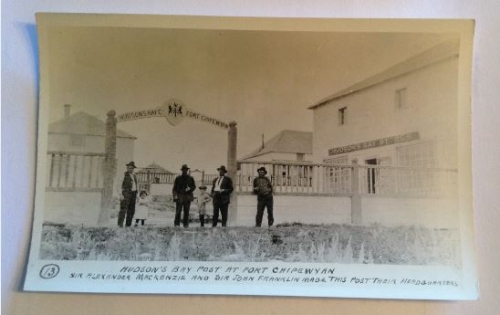

Yesterday, a small package arrived in the mail. Inside the envelope, I carefully retrieved an old, yellowed school notebook, and a series of black and white postcards.

My attention turned first to the notebook. On its worn cover, my grandfather’s name was printed in block letters. Below, in the space intended for a school grade, my grandfather had written the words: “Hudson’s Bay Company.”

Dated June 14, 1929 to January 11, 1930, the pages tell the story of my grandfather’s time in Fort Chipewyan and Fort McMurray as a fur trader.

My grandfather was just eighteen when he left England for Canada. Barely out of high school, John R. Pullman boarded a steamboat across the Atlantic Ocean, bound for a land he’d never seen. In the early summer of 1929, his steamer pulled into Montreal. And from there, he traveled by rail to Alberta.

In early July, his Northern Alberta Railways train pulled into Waterways, now a community within Fort McMurray. It took 25 hours to make the journey.

The following day, at 4:30 p.m., he departed on a paddlewheeler called The Athabasca River, built in 1922 by the Hudson’s Bay Company to operate between Fort McMurray and Fort Fitzgerald. It was July 5, 1929 when he arrived in Fort Chipewyan.

Within days of his arrival, he was working in the town’s Hudson’s Bay Store. The store was one small part of a broader colonial project that extracted resources from this land and turned those resources into high-status goods for sale in my grandfather’s home country.

And my grandfather had the privilege to work within this system because of the colour of his skin and land of his provenance.

Confronting the Past

As my jet descended into Fort McMurray at 10:30 this morning, I couldn’t help but feel a strange chill. I flipped to a passage in my grandfather’s journal dated July 3, 1929. He writes:

“Still raining hard. Arrived Waterways at 10:30 a.m., having taken 25 hours to travel 300 miles.”

I could imagine the same warm rain that greeted me upon my arrival coming down on my grandfather as he alighted his paddlewheeler 84 years ago.

And then again, another echo from the past. This afternoon, at 4:30 p.m., my plane left Fort McMurray for Fort Chipewyan, exactly the same time my grandfather’s paddlewheeler left Fort McMurray for Fort Chewyan 84 years ago.

The landscape has changed dramatically since my grandfather made his journey. As I flew over the traditional territory of Cree, Dene and Metis peoples, I saw the tar sands megaproject sprawl across the land. I’ve seen countless pictures and articles about this place. You may have, too. None of it prepares you.

I’ve heard others say this before me, but the magnitude and expansiveness of the project is simply unimaginable.

You have to see it with your own eyes to comprehend it — and even then it’s incomprehensible. The land is beautiful.

There’s much more water than I imagined. In the places where the boreal forest and muskeg have been cleared, the plants look like bruises and scars on the land.

Along the winding Athabasca River, dark tailings ponds sit literally on the banks of the river. As you fly past one site, you immediately fly over another.

Tears pricked my eyes. I was overcome with emotion.

Healing

On July 5th, about two weeks from now, hundreds of people will gather in Fort McMurray for the 4th Annual Healing Walk. In the words of Roland Woodward, an elder from Anzac, a community 36 kilometres southeast of Fort McMurray, the Healing Walk is “an opportunity to heal the land, heal the people.”

Clayton Thomas-Muller, a prominent First Nations activist and coordinator of the Sovereignty Summer, says of the Healing Walk:

“The idea was not to have a protest, but instead to engage in a meaningful ceremonial action to pray for the healing of Mother Earth, which has been so damaged by the tar sands industry.

“Members of the five First Nations of the Athabasca region and residents of the nearby town of Fort McMurray, Alberta, tired of the never-ending fight with big oil and its supporters in the Canadian government, had made a conscious choice to protect their way of life.

“This was done by turning to ceremony and asking through prayer and the physical act of walking on the earth for the hearts of those harming Mother Earth through extreme energy extraction to be healed.”

It has been two generations since my family was in this territory. Two generations later, this land is still being colonized for profits that are shipped away while the cost is borne most heavily by the people who have lived here all along. My job is to spend the next two weeks listening, learning and sharing stories from people on the front lines of tar sands expansion.

I feel grateful that my grandfather’s journal arrived when it did. The book made me realize that I only have a superficial and academic understanding of the histories that connect this country. Now that I have been confronted by my own family’s role in the colonial project, there’s a big part of me that just wants to hide.

As I sit on the banks of Lake Athabasca, I have been grappling with what it means to have personally benefited from the colonization of this stolen land. As I try to capture in words how it feels, I am stuck at the first feeling: shame.

I wondered if I should hide his story because it implicates my family. I feared that my family connection to this history meant that I was a bad person, or that my grandfather was a bad person.

But I’m learning that it is not as simple as that.

I’m learning that allyship is difficult, messy, and complex. An ally is “a member of the ‘dominant’ or ‘majority’ group who questions or rejects the dominant ideology and works against oppression through support of, and as an advocate, with or for, the oppressed population.”

Right now, working as an ally means leveraging my privileged access to media to share stories from impacted communities downstream from the tar sands. Becoming an ally is a continuous process, not an identity that we can pick up and claim, and it’s okay to feel overwhelmed.

I believe that I am like many Canadians who know on a deep gut level that they are implicated in the broken promises of the Treaties, that they and their society has become rich off stolen native land. I believe that we all need to know our true history, and to understand what it means to be Treaty Peoples.

And I’m learning that a starting place is to just listen.

Learn more about the Healing Walk, and how you can help from home.