How do humans justify the terrible deeds we commit? This question perplexed the Globe’s Konrad Yakabuski in his column last week on slavery in the United States and the murder in Charleston, South Carolina, of nine African Americans by a white racist. “It seems incomprehensible how anyone could have rationalized” slavery, he wrote. We all know what he means. Yet in a perverse way it’s also the easiest thing in the world to explain: white Americans simply denied the humanity of their black slaves.

The American Declaration of Independence begins: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal.” The sentence was drafted by Thomas Jefferson, who owned slaves. Many who voted for it in Congress owned slaves. President George Washington owned slaves. As one abolitionist observed, “If there be an object truly ridiculous in nature, it is an American patriot signing resolutions of independency with the one hand, and with the other brandishing a whip over his affrighted slaves.”

But it didn’t seem at all ridiculous to Southern slave owners or even to many Northern non-slave owners, for whom slaves were not people at all. Or more precisely, blacks were not people at all. They were, literally, dehumanized. Slavery, like genocide, was the fruit of racism taken to its ultimate logic.

As Yakabuski wanted to rationalize slavery, so scholars of genocide try to fathom how annihilating an entire people can be rationalized. Their insights illuminate both phenomena. Both constitute the logical extreme of denying another group its equal humanity, which is the essence of all racism. The difference here is that genocidaires have no use for the groups they exterminate while white Southerners needed black slaves to perform backbreaking plantation work.

Gregory Stanton, with Alan Whitehorn, has attempted to classify the “Ten Stages of Genocide.” Stage Four is: “Dehumanization: One group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects or diseases. Dehumanization overcomes the normal human revulsion against murder.”

Helen Fein introduced the concept of a moral universe, or universe of moral obligations, from which certain groups are deemed to be excluded. Normative moral considerations do not then apply to that group who can be treated exactly as those with more power wish.

Eric Markusen and Robert Jay Lifton conceptualized the notion of a “genocidal mentality,” when ordinary people, led by elites, are persuaded that genocide against a particular enemy is necessary.

We can immediately see how these insights apply to the Holocaust — Jews were called “vermin” — and the genocide against Rwanda’s Tutsi, who were called “cockroaches.” But they seem to me equally applicable to other morally equivalent man-made calamities like apartheid, the treatment of Aboriginal people and certainly slavery. The key is the racist belief that another group is inherently inferior, not human, or at least less human than whites. Everything ugly follows.

Nor did this belief disappear in the United States when slavery was formally abolished during the Civil War. Other forms of virulent anti-black discrimination endured for the next century, some tantamount to slavery, and racism of various degrees operates against black Americans to this day.

I saw it for myself in the early years of the civil rights movement, when three Canadian university students travelled at length through the Deep South. At every stage of our journey we found the situation far worse than we had imagined. Whites hated far more ferociously and blacks remained far more terrorized than we had understood. And we quickly discovered that the only way to make sense of it was the abiding certainty among whites that while all humans were created equal, blacks were still not human and certainly not equal.

Of course there’s no question that American race relations are dramatically better now than they ever have been. But it’s not just the murders at Mother Emanuel Church that remind us how many white Americans still exclude African Americans from their moral universe. The examples are too well-known to need repeating here — schooling, prisons, employment, housing.

But I would point to something else, and it represents the country’s greatest contradiction. On the one hand, a black man was elected president, giving us on November 4, 2008 one of the awe-inspiring nights in America’s often shameful history. On the other hand, many Americans have never accepted Barack Obama’s legitimacy because he is black.

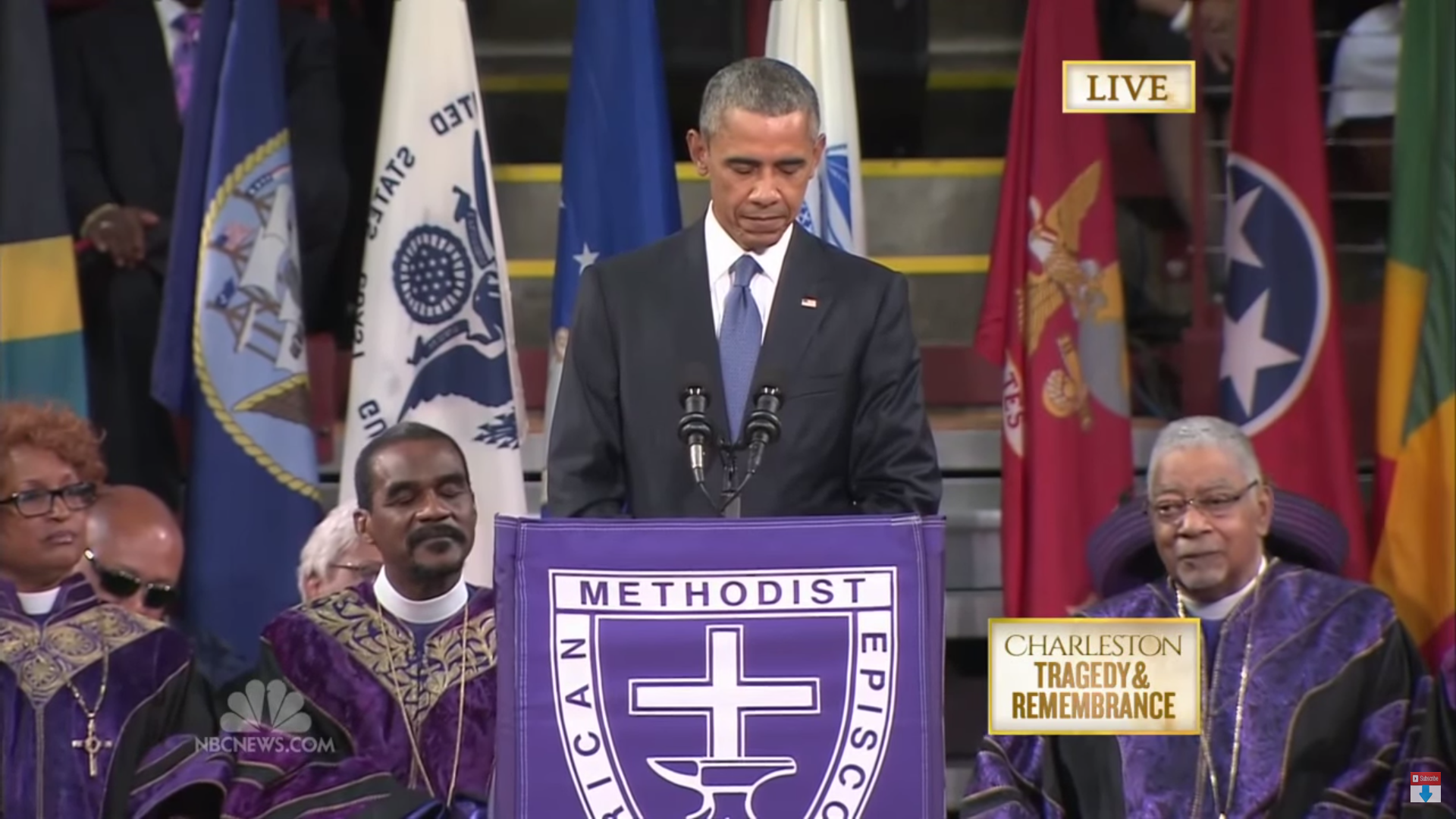

Obama remains outside the moral universe of tens of millions of Americans. A February 2015 survey found that 54 per cent of Republicans still believe he’s Muslim. In 2010 polls found that at least a quarter of adult Americans doubted he was even American. No other president has ever faced such contempt. I fear not even watching their president sing Amazing Grace at Mother Emanuel last Friday — the second magical Obama moment — will make these Americans believe that he, like all African Americans, actually was created equal.

Who can doubt it’s only a matter of time until the next monstrous racist crime makes the headlines? Like the Holocaust and Rwanda, we may understand it. But it remains incomprehensible.

This article originally appeared in The Globe and Mail

Image: Twitter/@WhiteHouse