Most people my age cite Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” when asked how they first became aware of the environment and the need to protect and preserve it. For many, the moment was the first Earth Day, April 22, 1970.

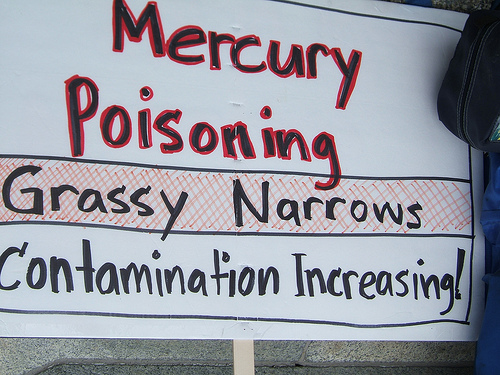

My moment of truth was the mercury poisoning at the Grassy Narrows Reserve in northwest Ontario. Between 1962 and 1970, two First Nations communities’ staple food — fish — had been contaminated with record-high levels of mercury from a chemical plant up the river. But no one knew, and for almost a decade they consumed the poison.

Much has been learned since Japanese researcher Dr. Masazumi Harada first visited the Grassy Narrows reserve and identified what would come to be known as Ontario Minamata disease. The first Minamata disease was documented in 1956 in a Japanese fishing village that shared a bay with a pulp and paper plant (not surprisingly, Grassy Narrows is also downstream from pulp and paper plant).

I would never have heard about Grassy Narrows if it were not for one of my house mates Maryanne — he was part of a group working with Toronto lawyer Norman Zlotkin to build a legal case for the band at Grassy Narrows.

I was reminded of all this this morning when an email arrived regarding the Tar Sands and mercury contamination. So much information on the devastation of the northern Alberta environment is being generated these days that I had apparently missed an important October 15 Globe and Mail story about a study — done, but not released to the public — by the federal-provincial Joint Oil Sands Monitoring (JOSM) program. JOSM’s creation in 2012 was in response to two devastating studies that concluded Tar Sands monitoring was woefully inadequate.

This was the third such study on mercury in the Tar Sands region. The latest conclusion was that

The mercury levels in the eggs of the predators studied paint a bleak picture. It means fish swimming in the lakes and rivers — not long ago pristine — were contaminated with mercury. Authors of the reports were careful not to point the finger at the rapid expansion of the Tar Sands as a potential cause, but amazingly suggested Chinese coal fired power plants could be the culprit.

Here in Ottawa, I once stormed out of a government consultation on mercury pollution in frustration over the benefit of the doubt afforded to industry…but I digress.

Based on the experience at Minamata and Grassy Narrows, shouldn’t we be asking what is happening to the (mostly) Aboriginal peoples eating these contaminated fish?

A generation ago, governments and industry in Japan and Canada forced victims of mercury pollution to mount legal and political battles before doing the right thing and protecting their citizens’ health. Here we are today and government and industry are behaving the same way. Fifty years ago they could legitimately claim they didn’t know what was happening, but not today.

Precautionary Principle

Ignorance is never an excuse and willful ignorance is criminal. Though much more scientific work is needed, there is already enough evidence to support two immediate actions that have not been taken:

1. Conduct a comprehensive health study of the people in the Athabasca region; and

2. Make it mandatory that industry install mercury scrubbing technology in all their stacks.

Until there is clear evidence that mercury levels have started to fall in the region, this is the only logical and ethical approach. It’s not rocket science.

Turning a blind eye to Tar Sands health impacts on native communities is not only criminal — it’s immoral and must stop. Haven’t our First Nations been through enough already?