Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Fish from the English-Wabigoon River System have up to 150 times the safe daily dose of mercury, but a wholesale clean up could end the damage caused decades ago when the pulp and paper industry dumped heavy metals into the river system.

Earlier today, researchers announced good news to members of Grassy Narrows First Nations (Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation) that a clean up of the English-Wabigoon river system is still possible.

While the initial contamination occurred decades ago, the effects of heavy metal poisoning has devastated the small Treaty Three area, both on and off reserve. And the impact is unfortunately both multi-generational and still presently experienced by community members.

They rely upon the English-Wabigoon river system to provide their community with fish, as the cost of purchasing other forms of protein for their diets can be prohibitive. While their health is very important, that is not the only concern. They have a right to live and gather food within their traditional territories, a right re-affirmed by Canada’s adoption upon signing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

The first of the UNDRIP’s 46 articles declares that, “Indigenous peoples have the right to the full enjoyment, as a collective or as individuals, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms as recognized in the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights law.”

The Declaration goes on to guarantee the rights of Indigenous peoples to enjoy and practice their cultures their customs, their religions and their languages; to develop and strengthen their economies and their social and political institutions. Indigenous peoples have the right to be free from discrimination and the right to a nationality.

Chretien’s musings concerning why a First Nations community doesn’t simply move and relocate as a solution is simpleminded. It also unfairly blames the victims for the circumstance they find themselves in. It defies logic to blame the residents, both on and off reserve, for allowing pulp and paper mills to operate within their territory because they benefitted from the good jobs these factories provided community members.

The Anishinaabe experienced mercury poisoning from Dryden Chemical Company, a chloralkali process plant in the pulp and paper industry, located in Dryden, Ontario, as well as the Dryden Pulp and Paper Company. Both ceased in 1976, after 24 years of operation.

Grassy Narrows First Nation received a settlement in 1985 from the Canadian government and the Reed Paper Company that bought out the Dryden Pulp and Paper Company and its sister-company Dryden Chemical Company, but the mercury was never actually removed from the water.

The fish from the English-Wabigoon River System have up to 150 times the safe daily dose of mercury.

The provincial government at one point decided the best way to solve the mercury contamination and resultant Minamata disease was to recommend that no one eat the fish from the rivers. But again, this was many community member’s primary source of protein, as well as the land and water representing a cornerstone to the community’s definition of self, and a source of spirituality to many.

Premier Wynne has so far not agreed to finance a wholesale clean up, despite repeated attempts by chiefs, council members and community members begging her to do so, because it could save lives.

Grassy Narrows has also sponsored many different River Runs over the years in Toronto, when they link up with other stakeholders to pressure the Liberal government to do right by the First Nationc community; including one year sponsoring a fish fry and inviting government representatives to the table, offering them locally caught fish.

If government officials refused to eat the fish caught up in Grassy Narrows — as they did — there must be a reason for that fear; it pretty boldly illustrates that the river, the fish, and the people who live near it are sick, despite initial denial.

John Rudd, a lead author of new research commissioned by Grassy Narrows First Nation and released today, is hopeful that a clean up is still possible. But this hope is married to frustration since scientists like Rudd first proposed recommendations for a clean up back in the 1980s. The cleanup could cost “several tens of millions of dollars,” Rudd said.

Rudd said the source of the ongoing contamination needs further study, but the feasibility of remediation does not. CBC News reported that Rudd had mentioned that mercury cleanup methods recommended by him for the English-Wabigoon, and rejected by the government in the 1980s, have since been seen to work, successfully, at an estuary in Maine, Rudd said. New technology has made remediation even more viable, he said.

After Rudd made the announcement, the provincial government announced that it had reviewed Rudd’s new report and disagrees with the conclusions.

“Currently there is no evidence to suggest that mercury levels in the river system are such that any remediation, beyond continuing natural recovery is warranted or advisable,” Gary Wheeler said in an email to CBC News.

If Gary Wheeler believes that mercury levels are low enough that fish caught in those rivers are indeed safe to eat, then as an ally to Grassy Narrows, I again invite him and the Premier to sit down with community members over a lunch of locally caught fish.

After all, what is he afraid of if he’s claiming that there is nothing wrong with the fish?

Grassy Narrows is hosting enough River Run this year in Toronto. Toronto allies are asked to meet at the provincial legislature at 12:00 p.m. noon on Thursday June 2, 2016. More information can be found on this Facebook page.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

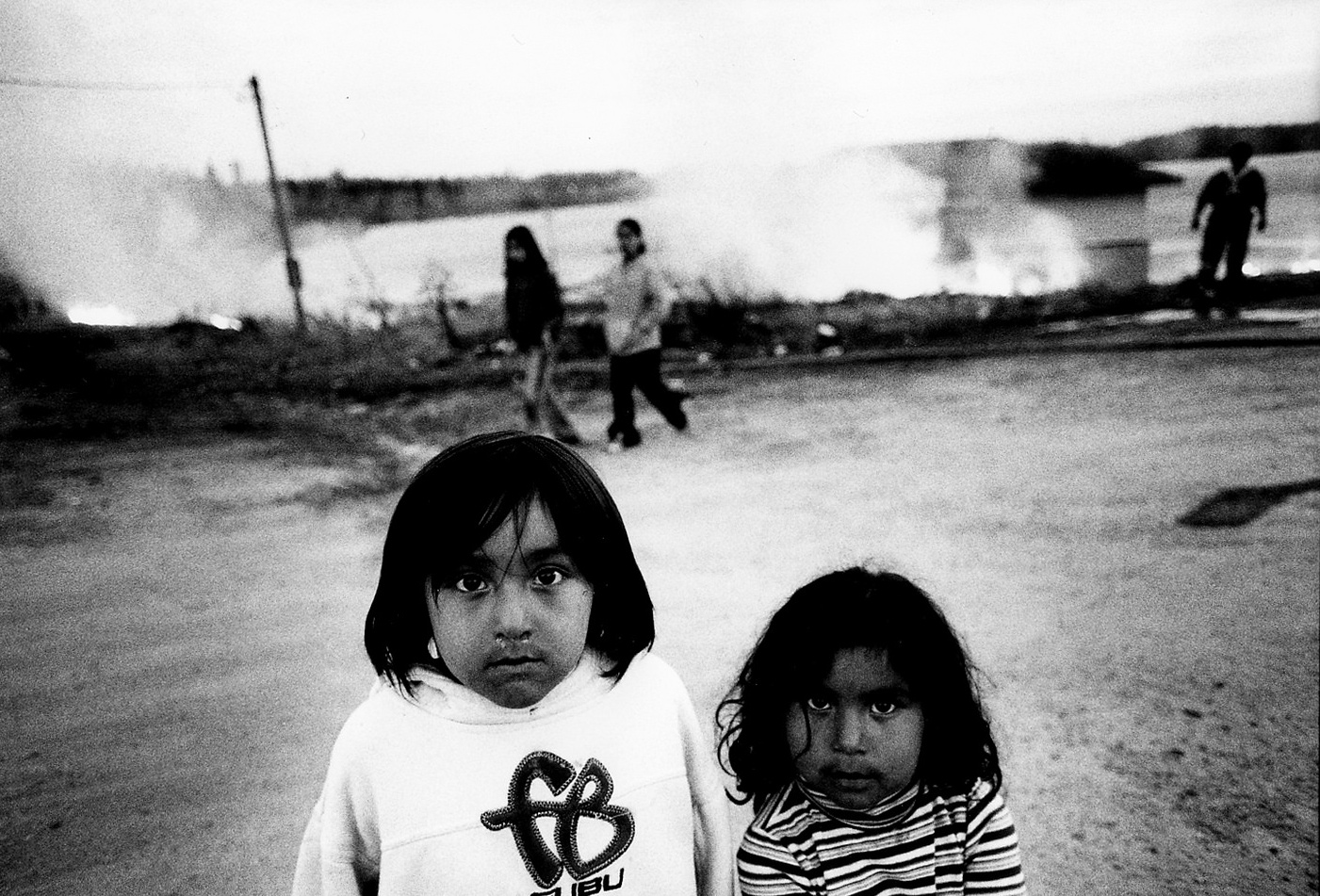

Image: Flickr/Howl Arts Collective