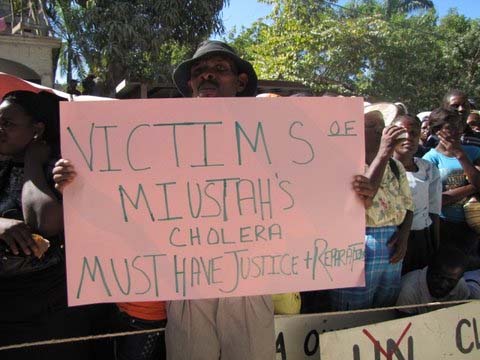

On December 9 last year, several thousand Haitians took to the streets of St. Marc, a small city located north of Port au Prince, demanding that the United Nations pay compensation to people who have contracted cholera (here is a 10-minute video of the action). Demonstrators blamed the UN for negligence in failing to screen for the bacteria carried by the foreign soldiers of its military occupation regime known as MINUSTAH, improper treatment of the human waste on its bases, slow response to the epidemic when it broke out in October 2010, and denial of responsibility (to this day).

Researchers at Harvard University recently reported there is a “mountain of evidence” that cholera was carried to Haiti by Nepalese UN “peacekeepers.” Previous reports drew the same conclusion.

The Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), a U.S.-based rights group, and its Haitian partner office, the Bureau des avocats internationaux, have launched a lawsuit on behalf of 5,000 cholera victims. The victims are demanding a statement recognizing culpability, an apology, measures to prevent further spread of disease from UN police and military bases, and hundreds of million of dollars in compensation. The legal agencies will go to court in Haiti or the U.S. if the UN does not respond to the claims.

FADISMA (Faculty of Law, Santa Maria, Brazil) has also filed a complaint with the OAS’s Inter-American Commission on Human Rights demanding that the United Nations accept full responsibility and offer reparations for the actions of the MINUSTAH military base located in Mirebalais, Haiti. In addition to compensation, both the IJDH and FADISMA have called for the UN to provide the public health infrastructure for water and sanitation that is necessary to eradicate cholera in Haiti.

The cholera epidemic began in October of 2010. Before then, the disease was unknown in Haiti and Dominican Republic for at least a century. More than 7,000 people have died and nearly 500,000 have been infected. The introduction of the disease has been traced to a MINUSTAH base of Nepalese soldiers near the city of Mireblais. The soldiers dumped their waste, or allowed it to leak, into a tributary of the Artibonite River, the largest river in Haiti. Haitians use the river for laundry, bathing, drinking and irrigation.

The Haiti Relief and Reconstruction Watch project of the Center for Economic Policy Research in Washington, D.C., has accused the UN of lying about its role in introducing cholera into Haiti. Mark Weisbrot, a director of the project, wrote in The Guardian last month in reply to statements by UN Deputy Special Representative for Haiti, the Canadian Nigel Fisher, that, “The cholera strain we have in Haiti is the same as the one they have in Latin America and Africa. They all derive from Bangladesh in the 1960s so they are all an Asian strain. “

The UN’s own report from May 2011 contradicts that statement, says Weisbrot. It stated, “basic bacteriological information indicates the Haitian isolates were similar to the Vibrio cholerae strains currently circulating in South Asia and parts of Africa, and not to strains isolated in the Gulf of Mexico [or] those found in other parts of Latin America.”

Indeed, it seems that the strain of cholera that reached Haiti is more virulent. John Mekalanos, who chairs the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics at Harvard Medical School, said during the release of the aforementioned Harvard report, “What scares me is that the strain from South Asia has been recognized as more virulent, more capable of causing severe disease, and more transmissible. These strains are nasty. So far there has been no secondary outbreak. But Haiti now represents a foothold for a particularly dangerous variety of this deadly disease.”

The threat of cholera is by no means diminishing, especially following heavy rains. It is still killing hundreds of Haitians per month. Harrowing tales of deadly, localized infections regularly arise. Health agencies say that the underlying causes of the epidemic must be addressed. Poverty and a lack of sanitation, clean drinking water and public health education and services all contribute. The most vulnerable areas of the country are the many, remote rural areas.

Nearly four years ago, Partners In Health published a lengthy report, The Denial of the Right to Water in Haiti, that slammed international governments and complicit international agencies for the aid and development-financing embargo against the government elected in Haiti in the year 2000. Among the victims of that embargo were water treatment facilities that the government wanted to build. Canada played a lead role in imposing the embargo.

The cholera epidemic has heightened demands in Haiti for a withdrawal of MINUSTAH. The force spends a fantastic sum of money per year, nearly one billion dollars, while contributing next to nothing to human development. U.S. and other diplomatic documents released last year by the Wikileaks organization to Haiti Liberté weekly newspaper and The Nation magazine paint a picture of a brutal, ineffectual and polluting force.

Kim Ives, an editor of Haiti Liberté, will speak later this month and in early February at public forums and seminars in Winnipeg, Vancouver, Victoria and Seattle. IJDH staff attorney Nicole Phillips and Roger Annis will speak at public events in Toronto on February 16, 17. See the events page of the Canada Haiti Action Network for details.