Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

The Saudi government sure knows how to ring in the New Year. Nothing, after all, reflects a message of peace and hope more than a televised statement on Jan. 1 declaring the execution of 47 al-Qaeda “terrorists” by public beheading and firing squads.

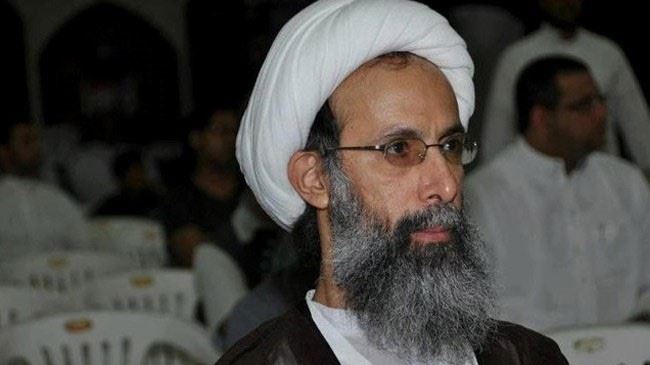

Except that four of those killed were not actually criminals — but champions of the country’s quietly repressed human-rights movement. Among them was the fiery reformist cleric Sheik Nimr al-Nimr and three of his followers, aged 21-24.

A little more than a year ago, I wrote about Sheik al-Nimr’s impending sentence of “crucifixion” (where the decapitated body is publicly displayed) after being convicted for “inciting terrorist offences” and “breaking allegiance to the king.” I spoke then to dozens of his followers, most in their 20s, who compared his calls for political reform and non-violent resistance to the likes of Martin Luther King, Jr.

It turned out the Shia cleric’s actual crimes were exposing the government’s callous treatment of political prisoners, questioning the very legitimacy of the Gulf monarchies on the basis that they were inconsistent with Islamic law and, perhaps most incendiary of all, calling out Saudi princes and princesses by name to stop “killing our sons.”

Like the perverse charges passed onto Saudi-born blogger Raif Badawi earlier this year, Sheik al-Nimr clearly crossed all red lines. He may have been a revolutionary hero to religious minorities across the Middle East, but to the Saudis he posed too much of a political risk.

Clearly though he couldn’t be portrayed to the world as such — so he was used as a pawn to settle scores with Shia Iran. “What the Saudi Arabian authorities have said so far indicates they regard these executions as taken to preserve security,” Amnesty International’s Middle East and North Africa director Philip Luther said. “But the execution of Sheik Nimr suggests they are using execution to settle political scores.”

From the failing Saudi-led (and Canadian endorsed) war on Shia Houthis in Yemen to the bloody al-Qaeda and Islamic State massacres against minorities in Syria and Iraq, Shias — which make up the largest religious minority in the Middle East — have never felt so persecuted, says one prominent Shia leader based in London. Those living in Saudi are perhaps most vulnerable.

“The Shia in Saudi Arabia have been subjected to a systematic, state-sponsored persecution for over a century,” says Sayed Modarresi, in reference to a Human Rights Watch report which found that the country’s two million Shias do not receive equal treatment under the justice system, and rarely receive permission to build mosques or receive government funds for religious activities, unlike Sunni citizens.

“Whoever is calling the shots in Riyadh must be drunk at the wheel,” he adds. “This [execution of Mr. al-Nimr] is the first of its kind. No Shia religious leader of his seniority has ever been publicly executed anywhere, not even under Saddam’s Baathist regime, whose persecution of the Shia was almost identical to the Saudis.”

Before his conviction, Sheik al-Nimr’s most heated rhetoric came during his sermons in 2011, when Arab Spring-inspired fervour swept the region. The Saudi government did their best at that time to stem political dissent by decreeing a multibillion-dollar package of investments for its citizens, but Sheik al-Nimr’s voice proved too compelling to ignore: “The House of Saud and Khalifa [in Bahrain] are mere collaborators with and pawns of the British and their cohorts,” he declared then.

“It is our right, and the right of the Bahraini people, and all people everywhere, to choose our leaders and demand that rule by succession be done away with as it contradicts our religion.”

His eventual beheading — in true IS-style with a sword — and with no forewarning to his family members, should come as no real surprise. What is more telling is its shrewd timing — the choice to carry out the sentence on a public holiday where western news outlets and human-rights organizations are thinly staffed — and alongside alleged al-Qaeda terrorists.

“What really hurts us is how the Saudi regime is trying to mix the file of the peaceful protesters with the file of the terrorists,” one young Saudi activist in Qatif tells me. But from Riyadh’s perspective, it was perfect: Executing a Shia political dissident on the same day as Sunni terrorists would make the act look less sectarian.

So what happens now? So far, everything the royal family likely predicted: Mild condemnation from mid-level United States and European Commission officials; statements by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch highlighting the country’s worsening human rights record.

Of course, Canada, the U.S. and the U.K. will press ahead with lucrative arms-trade deals with the Saudis, seemingly blind to the fact that they are arming the very people whose ideological roots gave birth to Islamic State.

How it is playing out in the region is a different matter. On Saturday, Iran’s top supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei vowed that Saudi will face “divine revenge” for the execution and posted a provocative image on his English-language website comparing Saudi Arabia to Islamic State, suggesting that they both execute their opponents.

That night, protesters came out in droves to storm the Saudi embassy, prompting Riyadh to publicly sever its relations with Iran and recall its own diplomats. Their allies, Bahrain and Sudan, followed suit.

More worryingly, two Sunni mosques near Baghdad were bombed and a Sunni imam was killed on Monday. Saudi police have also come under heavy gunfire in Sheik al-Nimr’s hometown, Al-Awamiyah, leaving one civilian dead and a child injured.

There’s no doubt the Saudis have succeeded in heightening sectarian tensions in the region. And while Sheik al-Nimr’s brother, Mohammed, immediately urged a “peaceful” response to the execution, saying the family’s “hands are still open for handshake and peace,” other followers may not be so forbearing.

As Mr. Modarresi notes, “Ayatollah Nimr was always warning followers against the perils of being dragged into armed confrontation. The sentiment is that if peaceful resistance can get an Ayatollah beheaded, there is no option but to resort to force.”

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

This article originally appeared in The Globe and Mail.

Image: http://www.freenimr.org/

Image: http://www.freenimr.org/