Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Jian Ghomeshi went to trial this month. And so, in a way, did Canadian women. The Ghomeshi trial is not only about a man who violated the four women pressing charges, but about whether we, as a society, trust women who tell.

It’s personal for me. Today and every day of February, I am sharing my own stories of sexual harassment and violence. Today is day 20(!), in which I share my experience of being called ‘jailbait’ by a man on a public bus. I am also proud to share a remarkable piece of writing by Kate Dunn, who experienced a sexual assault when she was 16. Please be gentle with her in the comments, as she is a very nice person and has chosen attach her name to her writing about this personal experience.

Me, on the other hand…

Nah. Be nice to me, too.

If you’re joining us now, may I suggest that you start at the beginning, by reading my introduction here. And remember, practice self-care. The Ghomeshi scandal has one hell of an undertow.

***

This is incident number five.

I was 12. I was a bookworm, an introvert, an artiste — and had been raised by the same. I loved adornment in the same way I will always love adornment. Which is to say: I really like shiny things and if I can find a way to put them on my body, I will.

Of course I loved beads. These were the days before everything was made by poorly paid overseas workers; beading was an expensive hobby. We didn’t have much money. Yet spending my allowance on small baubles, my babysitting money amassing useless sparkly things, seemed appropriate to me.

My mom was away for a few days that summer, probably having taken my sister camping with her friends. I was always invited to go on these trips but never wanted to. The idea of spending time home alone appealed to me, even if it meant scaring myself to sleep watching The X-files or reading The Exorcist and eating bagels for dinner. I could also help the family by showing a studio rental unit on the property to prospective tenants. My mom, now says that it was a mistake; that she wouldn’t leave her preteen daughter home alone for a week if she were to do it again. I’d say she’s right.

I was returning from Country Beads on West 4th in Kitsilano. I was wearing a short velvet tank-top I had picked out of a bin at the Le Chateau downtown (remember when Le Chateau was made in Canada and had a good supply of patent leather hats?), a belly-chain with an amethyst pendant on it, and tight pants. My mom probably would have told me to go back to my room and change, had she been home. Again, in the present day, as an adult woman, I’d say she was right. But that’s what I was wearing. It was an outfit, not an invitation.

I hopped on the bus, my new purchases in hand, and proceeded to a seat near the back doors. A man in his 30s made eye contact with me and I smiled a little. I sat down.

The man was quiet for a few minutes. Then he said, “Jailbait, you’re nothing but jailbait. You’re fucking jailbait, that’s what you are, jailbait.” I was completely taken aback. I had no idea what ‘jailbait’ was, but I could tell he wasn’t complimenting my shoes. The man’s face was red and he was sitting only a few feet from me.

I felt like a hot metal net had been cast over me. I wished I had a sweater. I asked him to please be quiet. He said no, that it’s a free country and he can say whatever he wants. I was all out of assertion after that one fledgling attempt. He continued to berate a 12 year-old for being too young to consent, his face getting redder and his eyes wider.

There were several other people sitting near us. I didn’t look up to see them watching. Nobody said anything.

I got off at my stop, just a block from my house. I didn’t know what I would do if the man got off with me and followed me home. But he didn’t. There was a woman getting off at the same stop and asked if I was OK. I said yes. She said that she was sorry that happened. I said that, well, everyone can have their own opinion. She said yes, but that it wasn’t right and shouldn’t happen. She asked again if I was OK and I reassured her.

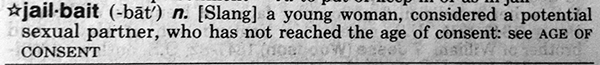

I walked the block to my house and immediately, directly, went to the dictionary above my mom’s bed. I still have it! It’s in front of me right now. This is the page that I looked at 20 years ago.

The definition contained none of the rage that the man on the bus had spewed at me and therefore felt incomplete. I wondered what part I was missing, unable to read through the lines with virgin eyes. The book was published in 1988, after all. It can be a bit oblique. I wondered where the word ‘disgusting’ had gone, or other nasty words like, ‘whore’, ‘trash’, and ‘nasty’. How could it be slang and not derogatory? It even sounded a little affectionate — after all, isn’t that how one would treat a ‘potential sexual partner’?

As an adult, I encounter the word infrequently, in casual, joking contexts. It still sounds sinister.

***

The issues this event brings up are similar to those I discussed on day two, in which I shared a memory of being accused of stealing by a man who also found me “disgusting” and volunteered that he “didn’t want to touch me.” Again, I’m writing about the chaos of my childhood, the necessities of a financially strapped, single-mother family.

Home alone, taking the bus alone. The sexual rage of a much older man, projecting his disgust onto the unsuspecting object of his fixation. And my need to incorporate this experience into my sense of self: on Salt Spring Island, I removed all the items from my jean shorts pockets, trying to prove to myself that I had done nothing wrong. In Vancouver, heading straight to the dictionary, I tried to understand just what this man had been saying, what line I had crossed.

I am amazed at how blithely I parroted the man’s justification of his harassment (“It’s a free country”/”Everyone can have their own opinion”) back to the woman who was, albeit belatedly, trying to help me. As if, in joining the man in his beliefs, I could switch sides and no longer be the weak, disgusting object he saw. I hate that I did that, but I was just being human.

We often internalize abuse, adopt the values of those more powerful than us in hopes they might not pick us the next time they sweep their surroundings for a likely victim.

And while we’re here, can we talk about the word ‘jailbait’? It’s an old term, from around 1930, and it does have that old sound to it. Like ‘box your ears’ or ‘pugilist’. It simultaneously objectifies the person it describes while ascribing immense seductive power to her.

She is a lure, a siren, a trap; a man might fall into her talons and find himself — poor hapless chap! — locked up for the next 10 years. Almost like he didn’t mean to. Almost like it was an accident that could happen to anyone.

In my utopian future, we will excise it from our vernacular, but maybe we could keep it in the dictionary. A relic of bygone days, when a girl couldn’t fight back because she didn’t know what crime she had committed.

***

The following piece is by Kate Dunn, who is also my step-sister-in-law and a remarkable person and soap-maker. Please send messages of encouragement to her via my Twitter account, @SveaVikander, which is being volunteer-staffed by another inspiring woman. The utopia feels near at hand with women like them around.

When I was 16, I was sexually assaulted by someone I considered to be a friend.

I didn’t fight back, I didn’t yell for help, and I only said “no” once. I didn’t protect myself. I let it happen. These were the facts I internalized immediately after the assault. I had considered myself to be strong, capable, and independent, and suddenly I was having to reconcile that self image with someone who, in my mind, wasn’t any of those things.

So I buried it. I convinced myself that it hadn’t been that bad. That maybe I’d actually wanted or encouraged it. Maybe I’d imagined it. Maybe I should just forget about it.

I continued to see my attacker socially, and didn’t tell anyone what had happened. At one point I even wrote something in my diary about being attracted to that person because if I was attracted to him then what had happened wasn’t assault, and I hadn’t been a victim. If my sexual assault had actually been a consensual encounter, then I didn’t have to adjust my self image at all. I was still that strong, capable person.

A few weeks later I reread what I’d written in my diary and burned those pages while crying.

It took me years to come forward and tell anyone about what had happened, and when I finally did I left out a lot of details. I finally allowed myself to acknowledge that it had happened but I changed the story, told people I’d resisted more. I was too embarrassed to tell anyone that I’d just let it happen. That’s how I saw it — I let it happen. I didn’t protect myself.

Years went by, and sexual assault became a more openly discussed topic. I started to learn that my response hadn’t been abnormal, that “freezing” was very common. I finally started to internalize the idea that the assault wasn’t my fault, but it didn’t matter. The initial assault wasn’t the problem anymore, it was my response to it.

I still felt weak and like I hadn’t protected myself, because I never reported anything. I didn’t go to the police, I didn’t tell my parents or friends, and I continued to hang out with this guy. I didn’t act like a “victim.” So, again, I buried it. I told myself that the assault hadn’t actually affected me that badly and that I’d been lucky to be so resilient. I told myself that I was so emotionally strong that I’d just shrugged it off, and that’s why I’d never reported it. Instead of being weak and scared, I was strong and capable.

Even now, 16 years later, I don’t talk about it. I’ve told a few people, and then let it drop. I’m mostly ok with my response to it now, and understand that how I reacted didn’t make me weak or any less of a “true” victim. I’m doing well.

But every so often, something will drag it all back up again, and I’m sure you know what that is now: the Ghomeshi trial.

I listened to these women, and I took some comfort from hearing them relate their responses to assault, both during and after, that are so similar to my own. And then I heard them being shredded for those responses and it made me sick. It hits hard against that fragile self image I’ve worked so hard to support, and makes me question myself all over again. I hear people saying “Why did they lie? Why can’t they remember everything?” and I think about how many details of my own assault I don’t remember, how much I lied afterwards. I hear people asking why they were all in contact with each other before they came forward, and why they were sharing their stories, and I think about how much I wish I could talk to someone else who had been assaulted by the same person.

Nobody wants to be seen as the person who continued a relationship with their abuser, especially under these circumstances. Common knowledge has caught up to the idea that abusive relationships can produce illogical responses in victims over time, but just reading the articles about this trial will tell you that the same acceptance isn’t given to those who were assaulted without a prior relationship existing.

Put yourself in my shoes for a moment and imagine how much it hurts to try to reconcile your own view of yourself with the reality of how you actually reacted. It’s bad enough to be the victim in the moment of the assault, but once you’ve spent years pretending it never happened it’s even worse because then you’re not just acknowledging that you weren’t strong enough to defend yourself, you’re also acknowledging that you weren’t even strong enough to believe it really happened, let alone report it.

So maybe you just pretend (again) that you won’t need to strip yourself bare in front of everyone. Maybe you convince yourself that those uncomfortable pieces of the story won’t matter because what he did was bad enough that everyone will focus on that. Maybe you organize with other people who share your story, make yourself feel less like a freak for having reacted the way you did. Maybe you finally decide, after you hear the same thing from so many others, that if you all band together and say the same thing, it won’t hurt so much to say it out loud.

As to those missing or wrong details? Science is finally showing that memories aren’t the solid, concrete things we like to believe they are. Every time you examine a memory, you change it slightly. A few details fade, others get imagined into existence as your brain fills in gaps, and you’re left with the kind of memory that has caused courts to place less and less reliance on eye witness testimony.

Now imagine how many times a sexual assault victim examines the memory of the assault, all through the lens of a traumatic and guilt-ridden experience. Think about how many details are going to be wrong, so many years later.

I’m saying all of this now, not because I want sympathy, or need support. I’m saying it because, somewhere, someone out there has gone through the same thing I did, and they need the support. They need to hear that they’re not alone and that if enough of us finally say something maybe coming forward won’t always lead to the kind of trial we’ve been watching play out over the last few weeks. That maybe one day, this will stop happening.

— Kate Dunn, 2016

Tomorrow: High school bullying and a success story.

Svea Vikander is a Swedish-Canadian radio host and therapist currently residing in Berkeley, California. Find her on twitter (@SveaVikander) and Instagram (@SveaVikander).

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.