Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Jian Ghomeshi went to trial this month. And so, in a way, did Canadian women. The Ghomeshi trial is not only about a man who violated the four women pressing charges, but about whether we, as a society, trust women who tell.

It’s personal for me. Today and every day of February, I am sharing my own stories of sexual harassment and violence. Today is day twenty-four, in which I share my experience of extreme vulnerability in the face of my son’s illness, and his specialist’s attempt to take advantage of it. If you’re joining us now, may I suggest that you start at the beginning, by reading my introduction here. And remember, practice self-care. The Ghomeshi scandal has one hell of an undertow.

***

My son was suffering from a medical illness (For his protection, I will not disclose it here and have changed significant details about the context of this incident, though not the incident itself) for which there was an absurdly long specialist wait list. The condition was not life-threatening in its early stages, but early intervention was advised. Every day that passed, my three-year old’s chances of having a complete recovery diminished.

My husband and I decided that we would pay out-of-pocket for a doctor outside of our insurance network. Few specialists in our area were taking new patients. After weeks of searching, I found a doctor who could see him right away.

With much excitement, I brought my son for our first appointment. The doctor was a past-middle-aged man who opened the door with a warm smile. His office was light and airy, in a part of San Francisco where creative people once lived. When I flipped over the consent form he handed me to sign, I noticed notes from another client’s chart lying underneath it. Large scrawl, not illegibile, including the patient’s name, age, and prognosis.

I paid $400 for that visit. Canadians, your gloating is expected and encouraged.

Several months later, I took the bus from work, listening to As It Happens on my phone, winding mindlessly through the city. I arrived exactly on time. The doctor welcomed me in and said, “I was just going to get a coffee…” The sentence hung in the air. I said that I didn’t need one. I said I would wait.

The sun was shining, and the window was open. It was one of those strange weeks in which summer in San Francisco feels like a summer almost anywhere else. The office was located in a renovated walk-up, in which the old windows, broad and white-trimmed, had been kept intact. The blinds were open. The sun on the trees made shadows on the concrete wall at the end of the property. Birds were literally singing.

He returned. He said that he had been playing in a poker tournament all weekend, and that he’s “actually quite good at it” and came second place. I noticed that a few of his finger nails were long and jagged, the bags under his eyes larger than usual, and a few white specks on his hair. He asked where my son was. I said that he was visiting his grandparents, but that he was doing well. That all I needed was a renewed prescription for him and I would be on my way.

Our conversation lasted over an hour. These are the parts I remember.

The doctor asked how I was doing. I said that I too was doing well, and very busy. He asked how my relationship was going. I said that it’s great. He asked how our sex life was. I said that we’re busy as the parents of two young children but that we make time for each other. He asked how my sex life was when I was a teenager. I told him that I had a lot of sex but few orgasms. He said that sex requires us to have progressed through all of Freud’s developmental stages.

He said that in his most recent relationship, the sex part had been “great, very good, actually…” but that she had once smashed a coffee table into the side of his head and that he had a scar from it. He said that she is crazy, but a surgeon. That she won’t leave him alone, calls him at all hours of day and night to yell at him, and that he has told her that she needs to get help before he can see her again.

I heard more. That her husband is a great guy, a very nice person, but he had forced her to adopt a child she didn’t want. That she uses substances and has two kids, one of whom told her teacher that she feels unsafe with her mother. That the child welfare system had intervened but that because his ex is wealthy, she was able to fend them off. He said that the child’s concern was ridiculous. I said it sounded like a terrible situation.

He looked at me and said that he couldn’t believe I had ever had any problems; that I seemed like the perfect woman. He said he was “very impressed” by me. I blushed and said that is a great compliment, and only tells me how far I have come.

I found myself looking outside, noticing the vines growing on the wall at the end of the property. There were houses on the hill behind it. It looked safe outdoors. Quite lovely, really.

He said that if I had a clone, I should let him know. After a pause he followed it up with, “Well, if she was a few years older that would be better, really…”

I wanted to leave right away. But first, I had to pay him for the appointment. As always, he fumbled through his scattered belongings, lifting papers, muttering, searching for his credit card reader. He said he would call me and I could give him the number over the phone. Remembering two previous rambling phone calls, I said I would prefer to give it to him now.

Once he found the reader, he asked, “So how long were we gossiping, how long were we actually talking about treatment?” I generously said we had been talking about treatment for 30 minutes. He told me that he would charge me for an hour-long appointment. I objected. He said that he hadn’t charged me a full intake fee, so this was fair.

I went to grab my bag to leave, and held out my hand to shake his but, as I expected, he grabbed me and held me. Said he didn’t see me as a patient so much as a colleague. As I left, I realized I could smell my entire, shaky body.

***

The day before our son’s next appointment, I explained in detail to my husband what had happened. He took our son to that appointment, and continued to manage all interactions with the doctor until the in-network referral was available. We decided that I should have a “no sleazy men” rule in my life: that when I interact with a man who is treating me inappropriately, I can either assert myself to him or the authorities, or simply disengage. I was excited but scared to make this stand, afraid to face its fallout.

A part of me had thought of the “sleazy superior” phenomenon as something from which I benefitted: that their power, through their attention, somehow rubbed off on me. That there was a trade of sorts going on, with me receiving some ineffable advantage in exchange for their advances. But when I ask myself what, exactly, I got out of the doctor who unzipped my pants, the boss whose friend groped me, the middle-aged psychologist who whined extensively when I said I wouldn’t go for lunch with him, my lonely and gaslighting Buddhist teacher, the supervisor who had excellent HR/underage preying skills, others I have not discussed, and the doctor who treated my son? I realize that…

No.

The sleazeball superiors in my life have done nothing for me. They have been a hindrance, a time suck, a tragedy, a taste of bile in my mouth.

I can make the stand to actively excise these tumours/men from my life in part because I have done a significant amount of self-examination, meditation, and therapy. But ultimately, this stand is possible because of privilege. I don’t need to work for a sleazeball boss because I have material security. I worry less that a man I reject will come after me, now that I have the privileges of a heterosexual marriage (in the patriarchy, I’m another man’s woman). The support of my husband allows me to trust my own instincts more. My ethnicity and the colour of my skin make me more “believable” to authorities, should I choose to report him.

The one thing that makes me more vulnerable now, at age 31, is the fact that I have children.

Children.

I have never been so rich and so defenseless.

Having a child is like walking around carrying a large and immensely fragile golden egg and hoping that everyone else will refrain from breaking or stealing it for no other reason than that it is unmentionably valuable. What pure insanity. Every day that I parent is an exercise in trust and surrender. My kids are badass rock climbers but they are also so fragile, breakable, needy, emotional, impressionable, attached.

The rest of the world knows this, and that you would do anything for your child. As a parent, you can only (ever!) hope that other people will not break your egg; and that they will have the decency not to use it against you.

There’s a scene in Forrest Gump where the schoolteacher has coerced Forrest’s mother into having sex with him. She does this in return for being able to enroll her low-IQ son in school so that he will have a more fulfilling life. Under duress, she chooses her son’s well-being over her own. Forcing a parent to make this choice is a specific kind of reproductive violence that we don’t much talk about. The betrayal that I felt when my son’s doctor began to seek a sexual connection with me was mostly about this.

I half-expect all men in power, even doctors, to abuse it. But this was a different situation. This man didn’t just have financial power over me, or a physical advantage. He had the force of the weight of my love for my child. I needed his goodwill to treat my son. And he knew it. He knew I would put up with, at the very least, a series of masturbation-worthy conversations. Because I have a golden egg who loves Thomas the Train.

***

Before you go, I have a little thing to say.

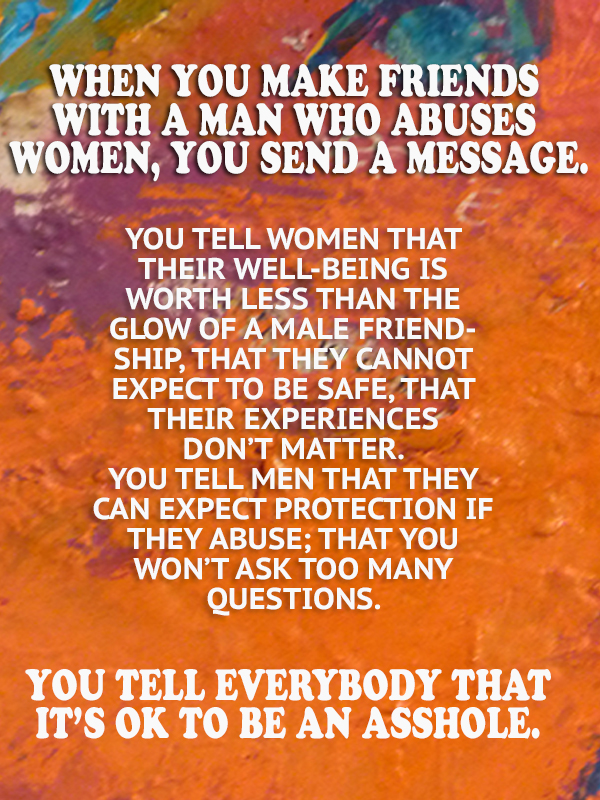

I recently discovered that a well-known Canadian artist I know and like is close friends with another, less well-known Canadian artist who sexually harassed a much younger and more junior Canadian artist friend of mine in the same field. I feel my breath sharpen as I say this. I am so angry. Also, that was a very long sentence. But yes, of course; we can all be friends with whomever we like. However, let it be said that when a man in power — a work superior, a professor, a celebrity, a parent — aligns himself with a man who has abused a woman, he is sending a message. A statement of his values and the values of the community he represents; for better or worse, and whether he likes it or not.

(I do not take full credit for this list, as it was created in concert with another woman)

Tomorrow: online harassment, y’all! (you ready, Vince?)

**

Svea Vikander is a Swedish-Canadian radio host and therapist currently residing in Berkeley, California. Find her on twitter (@SveaVikander) and Instagram (@SveaVikander).

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.