Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Jian Ghomeshi went to trial this month. And so, in a way, did Canadian women. The Ghomeshi trial is not only about a man who violated the four women pressing charges, but about whether we, as a society, trust women who tell.

It’s personal for me. Today and every day of February, I am sharing my own stories of sexual harassment and violence. Today is day 26, in which I share my experience of fielding abusive calls while volunteering for a crisis hotline. I am also excited to share a guest post from Kristie De Garis.

She relates some of her experiences, all of which are harrowing, and the emotional labour it costs to live a productive life through them. Kristie is one of the wonderful women who is monitoring my Twitter account while I do this project; she is a photographer and mother who lives in Edinburgh, Scotland, and all of the beautiful images in this post are her work (or from her personal photo album). I love them so much. I think you’ll find this post is a bit image-heavy. Because love. More of her work can be found here.

If you’re joining us now, may I suggest that you start at the beginning, by reading my introduction here. And remember, practice self-care. The Ghomeshi scandal has one hell of an undertow.

***

This is incident number 18.

The first thing I did upon moving to Toronto in 2002 was to shave my head. The next thing I did was attend a book launch in which the words, “Ubu thrusts. Ubu bucks. Cum spurts. Ubu cums” were read with much enthusiasm to a crowded room. My third priority was signing up to volunteer for a crisis hotline.

I had waited so long to do it. It seemed like a way in which I could support people without sacrificing my safety or study hours. My life goal at the time was to become a 55-year-old child psychologist wearing a pantsuit and speaking softly in an office. I knew that it would be a step in the right direction.

The hotline operated in downtown Toronto out of an old house that, because it was a priory, had survived even as its meager three stories were shadowed by high-rise office buildings. Its carpeted stairs were so skinny that walking up them I had the feeling I was falling backwards. They creaked. It was a nice place to be.

After an initial interview, I spent the next six weeks of Tuesday nights training in suicide risk assessment, reflective listening, and umming and ahhhing at the right time. It was good training. We role-played scenarios in which people called in with a variety of problems. We discussed angry callers. But we received little training on how to deal with men who sought a free, compassionate female body on which to unload their sordid fantasies. How to identify them. How to stop them. How to care for yourself when it happened.

I worked the line for several years. I spoke with hundreds, maybe thousands, of people. To my surprise, only about one caller in each four hour shift would be in a state of upset that we normally associated with crisis. Usually, callers talked about their children, illness, disability, legal battles, mental health, discrimination, and, perhaps saddest of all, told stories from their pasts that they needed someone else — anyone else — to know before they died.

I spoke with callers experiencing psychosis who would describe their persecutory delusions (“Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean you’re not being followed”) and callers whose stories and personalities would change right before my very ear. All of this was good, mutually beneficial work.

The hardest, most difficult calls, were the sex calls. Men who were calling to get off. I wanted so badly to be there for people who needed me. It was like a kick in the face every time I opened my heart to a stranger only to find them unzipping their pants and ejaculating into it.

When I began, I was 18. I am female. I had a young voice and truly cared. I was a sex caller creep magnet.

There are six types of crisis line sex calls. About half of them hit the ground running with sex as a topic and are thus easy to spot and shut down. The other half involve developing rapport with the volunteer over time, drawing her in and gaining her trust. They suck.

Sex Calls: An Anatomy

1. The one in which he tells you an emotionally compelling story with an obvious opening for discussing sexuality, such as being diagnosed with testicular cancer or struggling as a closeted gay man. There was no way in hell I was going to accuse callers with either of these stories of not being genuine, and they knew it.

2. The one where he breathes heavily and says lewd things until you hang up.

3. The one where he has previously built a rapport with you and calls to talk about his actual problems but slips in a few explicit and unlikely scenes for his own titillation.

4. The one where he tries to get information out of you: how old you are, what school you go to, if you have a boyfriend, what you look like, if you could beat him in wrestling, what about figure skating, or even monopoly, really any kind of humiliation would be OK to talk about?, etc.

5. The one where he just tries to get you to repeat dirty words:

Caller: I’ve been on the street for a long time. It’s very long… and hard…

Volunteer: that does sound really difficult

Man: No, I said hard. It’s very hard.

Volunteer: Mm-hmm.

Man: [fapping sound anyway].

6. And there’s the one in which the caller is irate for no discernible or reasonable reason, and the best insults they can muster are, as always, about your appearance and your rapeability.

The hotline was open 24 hours per day, with volunteers required to work at least one overnight shift per month. There could be a sweetness to these evenings. Coffee and cookies were available. The house was situated away from the street and in a wind tunnel, which would muffle outside noises. It could feel like the nearby office buildings themselves were taking a rest. And I liked walking home afterward at 6 a.m. when the city was populated by societal extremes: those who slept in the street and those who speed-walked it before their early morning meeting.

But the late night callers could be terrible. Out of respect for caller confidentiality, I will not share a specific instance here; but I can say that they were intensely fixated on speaking to me about their penises and that it’s a lonely thing to know when you’re the last one awake in the center of Toronto.

I remember sitting paralyzed at my desk, knowing that I should press the “activate” button to take the next call but not feeling that I could face what it might contain. In winter time, it would not yet be light out when I left my overnight shift; sometimes I walked home in the snow, but other times it just felt like trying to run through water.

Volunteers were required to take notes of the calls they took. I dutifully wrote down the grotesque fantasies to which I was being exposed. The supervisors read my notes and would frequently inform me that a call in which I had thought I was giving actual emotional support was actually someone else’s well-rehearsed narrative designed for their own sexual gratification, in which I had been an unwitting, unconsenting participant. At no point did a supervisor take me aside and ask me if I was OK with this.

The hotline staff and volunteers were on a first name basis with the regular callers. There was a standing file in the center of the phone room in which volunteers could look up and find information and adaptations of old notes about the people they were on the line with. Things like, “This caller lives in an assisted living facility and would be happy to tell you about her cats. Unless in crisis, limit calls to 20 minutes.” Some abusive callers were listed but there was no separate file of sex callers and their usual profiles or stories. This would have helped me so much.

I remember one short shift in which three out of the five calls I took were sex calls. All in a row.

The location of the hotline was a tightly guarded secret. But there is so much more to safety than a feeling of physical sanctity. The fact of not knowing whether the next call would be a person in crisis or a person in their altogether, and not knowing when they might reveal that latter fact, and not knowing if I would in fact pick up on their manipulation, was terrifying.

If the work had been handling consistent sex calls (as on sex lines, whose operators I respect very much) it would have been easier. But most of the time, the calls were made by people who really did want support, and for whom I genuinely cared; I had to keep the possibility open in my mind that the man talking about his noisy neighbours having sex could in fact be someone with social anxiety. I never got to a point where I could identify an abusive or sex caller and just say, “Oh, there goes another one, ha ha ha.”

It’s hard to convey the intensity of the fear and loathing I felt when I realized that someone I was trying to help was trying to exploit me. It’s like, let’s say, someone shouts from a window that there’s a fire and they can’t get out, and you grab a rickety ladder and climb up to them only to find that it was a ruse to talk to you about voting for Marco Rubio.

It’s like spending a year planning your best friend’s Pinterest wedding only to realize she’s marrying your boyfriend and is the reason why he grew a fucking goatee. Like paying $2.99 for an organic avocado only to find out that not only does it have a razor blade in it, it’s ALSO OVERRIPE. But instead of funny, make it sad.

***

I stuck with the crisis hotline because I knew I was learning something important about human nature, though I wasn’t sure what. Something about the crushing loneliness of being poor and housebound, or the need for a human voice to talk to before the pills kicked in. I had been so stupidly busy up until that point that learning to spend hours making conversation with strangers was humbling. Speaking with elderly people who had grown up in a different Ontario, an Ontario of trains and churches and towns ending in -ton, helped me to feel more connected with my deceased grandparents. In a big way, the crisis hotline helped me to fall in love with my new home.

But the issue of sexual harassment should have been taken more seriously. I wish I had realized that the experience I was having was not normal, and definitely not OK. That simply because I received more, and was more upset by, sex calls than the businessman operating the phone beside me, didn’t mean that my experience was invalid. I wish I had advocated more strongly for the small changes that could have made a big difference.

And I don’t hate the men who called. I can understand what would make calling a crisis line to masturbate seem like a good idea. It’s free. You can do it from the comfort of your own home. And there’s something about the human voice, the possibility the phone carries of real human connection, the fact that you can hear each other’s pauses, breaths, tones, catches, that makes audio almost as personal as touch.

Jian Ghomeshi felt like a trustworthy person to millions of people because he has a warm, sensitive voice. It was one of the reasons that the revelations of his abuses felt like such a betrayal to so many Canadians.

Plus, there’s a visual aspect to audio: because we can’t see the person speaking, we have to imagine them. In the days before radio personalities had to be internet personalities, Vicki Gabereau used to joke that she looked “almost identical” to Marilyn Munroe.*

*If you are a man who has masturbated to the voice of Vicki Gabereau, I can’t tell if I hate you or if I love you. Please get in touch.

Turning a volunteer-staffed public service into a source of fap fodder is similar to the exhibitionism I discussed on day 14. It involves men (and to be clear, yes, the sex callers were entirely men) experiencing a sexual or romantic problem and externalizing it. Instead of seeing their loneliness as a personal problem, they make it a social one. They put the burden of their satisfaction onto an unsuspecting volunteer who could have better spent her time at Robart’s library, at a minimally voweled poetry reading, or taking a weekend trip to Kingston.

***

Guest post: Kristie De Garis

Below, the powerful words of Kristie De Garis, a woman I’ve never met and who married an acquaintance of mine and who, through the power of social media, has become a dear friend. I feel compelled — for the first time in doing this project — to issue a trigger warning for her piece. She details some harrowing experiences and the way she tells it, well, it packs a punch. Please read at your own pace and in a setting in which you feel safe.

Every woman I know has been sexually harassed or sexually assaulted, most often both.

I’ve said that, written that, heard that, read that so many times that it has been assimilated almost completely into my reality. Normalised, and my sense of outrage has slowly been subdued. I too get on with my life knowing.

So, I get it, I get why it seems like it’s OK to put it behind you and get on with your life without thinking about it too much, without making a fuss, without pressing charges without ever really explaining how it affected you at the time and how it leads you to say nothing now.

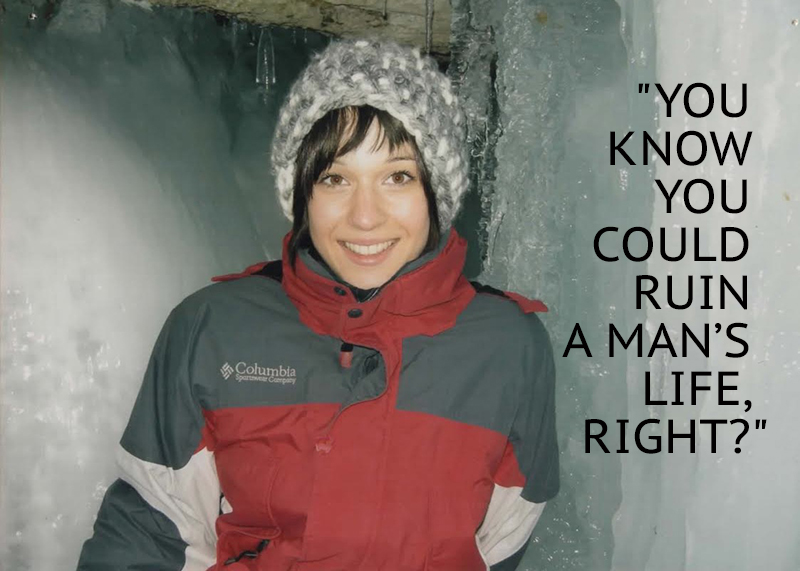

I’ve always been an outspoken person, I express how I am feeling and I find great relief and great healing in it; it’s who I am. I have been discouraged from doing this when I have been violated. The gentle, “Put it behind you, move on, that’s the real revenge” (as if revenge is what I wanted). The patronizing “Oh, that’s not a big deal, don’t make a fuss” (the word “fuss” denotes doing something unnecessary). The worrying, “You know you could ruin a man’s life, right?”

I am not ungrateful for the advice I have received because I don’t think any of it came from a willfully bad place. The people who gave it to me, I love them and they love me. It’s just become our reaction (if you could call it that?): to be passive in the face of all of this.

Here are the stats that rapecrisis.org.uk provide on rape and sexual assault. Approximately 85,000 women in England and Wales are raped every year, 1 in 5 women aged 16-59 has experienced some form of sexual violence since the age of 16, In 2012-13, 22,654 sexual offences against under-18s were reported to police in England and Wales with four out of five cases involving girls. You probably already know this, read this news item, were shocked by it, quoted the numbers to a disbelieving friend, linked to them on Facebook and my point is tied up in the fact that even though we all understand how prevalent these violations against women are, it’s fucking insane.

If every woman who was sexually harassed or sexually assaulted reported it to the police, the police wouldn’t have time for much else. I have never reported a time I have been sexually assaulted. I have also rarely been encouraged to.

My writing here is very much inspired by Svea’s project, which was in turn prompted by the Jian Ghomeshi trial. Her sharing of her experiences of sexual assault prompted me to delve into what were surprisingly difficult and numerous memories.

The time a much older man described to me (an eight-year old) how he liked to fuck his girlfriend, all while maintaining a gaze that both dared me to break it and warned me not to.

The time in my first week of high school when I was allowed to go into town with new friends who were unfathomably popular and inexplicably interested in me. I soon realised that part of this honour was allowing older male teenagers to touch me in places I had barely touched myself. I spent the rest of high school watching it all happen from the sidelines, a blessing even I recognised at the time.

The time as a teenager, I was sleeping deeply next to a female friend after a house party and was slowly risen by the movement of my own hips and (this makes me feel sick) pleasure. My friend’s boyfriend had climbed into bed with us and was fingering me and gently massaging my clitoris, like I was someone whose sexual experience he cared for.

I shoved him out of bed and he looked like he had been caught eating dessert before dinner. He shrugged an “It was worth a try” shrug and left calmly. I was manic. The girl next to me expressed how disgusted she was when she felt me moving “in that way” and had just tried to ignore what was happening.

She was as confused as I was by the pleasure indicated by my hips and judged me as harshly as I was judging myself. My friend, whose boyfriend had just violated me completely, called me a liar and then that call was taken up by all. It was a lonely time.

I saw him years later in a city street he looked the same, an unassuming man, scruffy, introverted and I crossed the road and I cried and I fucking hated myself.

The time after a disco the boy I was kissing grabbed me, shoved me up against a wall, pushed his fingers painfully inside me and then shoved them in my mouth. I had my period, it tasted like metal and it was the first time I had even considered what menstrual blood might taste like.

The time when I was in a club during my first year at university (I’d just moved from the back of beyond to a major city) and a man a lot older than me put his hand up my skirt and put his fingers inside me. He kept them perfectly still as we moved with the other bodies close around us, a silent, solid presence between my legs.

It was done purely to provoke me, while in the past it had felt like perhaps it was something that had excited the others involved. I was trapped by the slow moving revellers filing their way upstairs. I remember panicking but feeling physically and mentally unable to do anything. When I got to the top of the stairs he removed his hand and I heard laughing. I turned and I punched him in the face and I burst his nose.

I was then thrown out of the club, forcefully, literally thrown. Even though I explained why I’d done it, I was told never to come back.

When I was standing outside in the freezing wind trying to call my friends, the guy walked up, shoved me against a wall and pushed his fingers up my nose. “Smell yourself, bitch” he said. He laughed again with his friends as they walked away.

The times I was pressured by insidious mental games into sex. I see myself as a strong, outspoken woman. Even though I was successfully pressured into sex on numerous occasions, it almost feels like it didn’t happen to this girl, you know?

The time very recently when a freelancer within a professional setting called me a “fucking bitch” when I refused to engage with his aggressive conversational style (“Do you know who I am? You should know who I am. Your equipment is shit, mine is better…”).

The time when a stranger told me I “look like I need the shit fucked out of me,” a man I don’t know wants to “suck on my clit until I squeal,” some teenage boys I’m walking past with my daughters think I’m an “ugly fucking bitch.” I’m tired of it and I’m also tired of not reacting, tired of being told not to react.

On day seven of her project, Svea describes eloquently how I have felt many, many times. She highlights a huge problem that exists within our cultures.

“Why didn’t you say anything?

My mother taught me never to say “fuck off” to a man, especially a stranger. It makes them very angry.

In at least half the situations I write about this month, I remained silent, laughed it off, politely removed myself from the situation, or tried to charm the man/men who were violating me. It’s a thing that women do. It helps to keep us safe socially and physically. We are socialized to be nice, kind, polite; to keep the peace, and, as I said on Friday, do the emotional labor of keeping harmony in a tense situation.

A woman who fails to do this is often perceived as a trouble-maker, as a prude, as no fun, as unfeminine, as dangerous, as trashy, as lacking in self-respect. She risks incurring more harassment or violence. She risks a serious loss of social status.

Keeping the peace by not naming abuse is also very effective at keeping women physically safe. A man who is already violating a woman’s sexual boundary has demonstrated that he just doesn’t care much for boundaries at all. Outright rejection is a trigger to violence for many men. A woman has no way of knowing how far he is willing to go. Rape? Murder? Swing dancing? The safest thing in the moment is, usually, just to keep him happy.”

I started to think about this feeling of needing to “keep the peace” that I have felt especially during and after these aggressive encounters; but also how it permeates my many decision-making processes as a woman.

“A woman who fails to do this is often perceived as a trouble maker”

The guy who called me a “fucking bitch” at work really bothered me and I complained to the person who hired him. The response was pleasant but “I’m very disappointed that he behaved in this way and I will speak to him about it” was preceded by a list of reason why it was essential he was hired and also, “I’ve met him several times and he’s always been cheerful and polite.”

I was dismissed, I wasn’t believed. As if I were causing a fuss by bringing it up. I’m not sure if he was ever spoken to; he has been hired since and I look forward to avoiding working with him (at possible detriment to my career) and leaving or feeling wary if I find myself in a situation where he is there.

I highly doubt he even recognises how wrong his behaviour was. I’ve been told by others that they think he was probably joking. Does the fact I don’t find it funny mean I don’t have a sense of humour?

I’ve also been told the guy was “rude.” No, rude is having bad manners. Calling someone a “fucking bitch” is an act of aggression. I have been cautioned that it could damage my career prospects to make anything more out of this and you know, I feel that pressure too.

This scenario on the surface seems so far from a violent sexual assault and it is. I would argue, however, that women experience this feeling of pressure often, in all situations of sexual violence. Pressure to not speak up, pressure to not make a fuss if you speak up and are met with dismissal, pressure to “let it go,” “get on with your life,” “don’t be a drama queen,” “don’t make a fuss,” “don’t be so serious/intense,” “have a little fun,” “learn to take a joke.” And my favorite: “What a psycho.”

Women deal with these microaggressions every day and after a while, every single act of aggression, no matter how small, becomes a big deal. We are forced to carry an emotional burden by not reacting, not showing our rage or terror. Our encouraged stoicism is a labour. It’s been said before but I can’t get my head around how, instead of the perpetrators, it is us, the victims, that are expected to bear this burden.

It is us.

I have spent my life afraid to be the woman who won’t take your shit. People who know me will find that hard to believe but yep, what you’re actually getting is Kristie-lite. I am still silently, daily, taking a lot of shit. I lower my eyes and walk faster when I see a group of men on the street, I try not to let it ruin my day when they say something and I try not to let the anxiety, that is born of this happening so many times, control my movements.

I don’t want to cross the street to avoid groups of guys, although I often do. I outwardly agree when people tell me that I should let it go and that it’s not a big deal, because it bothers me to be perceived as someone who causes a fuss. It plays havoc with my self esteem. So much of my sense of self is derived from being capable, standing up for myself and others. I pride myself on being someone who doesn’t allow things that aren’t right to go unchallenged.

My mum always taught me to choose my battles carefully, but I find there are now too many battles to choose carefully. Whether I show it or not, I’m fighting them all.

– Kristie De Garis, February 2016

***

Whew. Big hugs to all the women who have been told not to make a fuss. Your fuss is beautiful and important. Tomorrow, let’s go a little lighter and I’ll tell you about the time a stranger bit my finger in front of his wife.

Svea Vikander is a Swedish-Canadian radio host and therapist currently residing in Berkeley, California. Find her on twitter (@SveaVikander) and Instagram (@SveaVikander).

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.