On Friday, June 5, I joined thousands of people on Parliament Hill for a rally against police brutality and to affirm that Black lives matter. My sign said: “Dear white people:/Stop the foolishness/Accept the inevitable/Share the privileges.”

The foolishness is the centuries-long history of systemic anti-Black racism in Canada that has led to the under-representation of Black people in graduating classes but our over-representation in jails. It also includes police killing Black people, which continues today, and the less spectacular forms of anti-Black racism that Black people in Canada deal with every day.

Systemic discrimination leads to certain groups being privileged over others. In Canada, the privileged group is often white people — hence my sign’s call for white folks to share the goodies. I found out first hand that some white folks don’t like being asked to do that.

I live in Ottawa and work for the federal government. In 2017, I cofounded the Federal Black Employee Caucus (FBEC). FBEC supports efforts at the national, regional and local levels to address issues faced by Black federal public servants. Shortly after we formed FBEC, my managers started imposing one sanction after another on me. Up to that point, I had worked with the government since 1999 virtually sanction free. In early 2018, I filed a union grievance against a manager, revealing that I live with depression, and citing the impact that discrimination was having on my mental health.

The next day, I was directed to have a medical exam to prove I was fit for work and ordered to leave the building immediately, or else security would remove me. Unknown to me at the time, while I was away getting the medical exam, I was banned from all departmental buildings, and a picture of me was circulated to the security guards telling them, “Don’t hesitate to call 911 if Robin turns up and shows signs of violence.”

I did show up, at my Gatineau office, to submit my medical exam. If the security guards had called 911 when they saw me, I could have ended up with a knee on my neck. And I’m not alone. FBEC pushed to have data on Black employees put back in the 2019 Public Service Employee Survey after such data was quietly removed years ago. The survey showed that Black federal public servant employees report discrimination levels twice the average.

A 2016 report on race-based traffic stops by Ottawa police showed Black drivers were stopped 2.3 times more than expected based on their driving population, and Middle Eastern drivers were stopped 3.3 times more. As the parent of two teenage Black boys, I am scared every time either of them leave the house, in a car or on foot. Despite having had “the talk” with them about what to do if they’re stopped by police, I am still scared. I’m scared they might get unfairly accused of stealing while shopping. I’m scared they might be attacked by someone who doesn’t like the way they look — and I’m scared they might be stopped — and possibly killed — by police.

I am also afraid that my schizophrenic older brother, who lives in Toronto, might be shot by police as so many other young Black men with mental health issues have been shot by police across Canada. Luckily, my brother continues to benefit from Ontario’s health-care system which has workers from the Canadian Mental Health Association check on him regularly. I am convinced that this has kept him alive.

A number of the people at the June 5 march had signs saying, “Defund the police.” This calls for the transfer of funds from the police to non-lethal, compassionate forms of intervention in cases of people having mental health crises. My brother is a living example of how well this works.

Education is another place where systemic anti-Black racism is deeply rooted. Neither my sons nor I have ever had a Black teacher in the public school system. If not for their mother being one of the few Black principals in the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board they would never have seen Black people in leadership positions in education. We have had to advocate on behalf of both our sons many times to address racial bias. One story stands out.

One day at dinner, when our younger son was around 12, I asked him what happened at school that day. He said they learned about the history of French settlement in Canada. When I asked him if they were learning it from the perspective of the settlers or their slaves, he said they didn’t cover slavery. When I emailed the teacher, he confirmed they didn’t cover slavery in Canada — despite it being a requirement of the curriculum. We demanded a meeting with the principal and the teacher, and raised hell.

Our son never had any more problems, but we don’t know if any permanent changes were made. Permanent change is being made now, however, as the board is in the process of collecting identity-based data on things like suspensions, expulsions and streaming that the Black community has long felt disproportionately impact Black students. Ontario’s Anti-Racism Act, adopted in May 2018, required the board to set targets for collecting identity-based data within 12 months. The board conducted their first survey in January, 2020 after much community pressure.

I have often wondered what part growing up with systemic racism has played in my depression — and concluded it probably played a big part.

I was born and raised in Halifax, Nova Scotia, home to Canada’s largest and oldest Black population. When I was born, Halifax was a very racially divided city with the south end being mostly white and wealthy, and the north end being mostly Black, working class and poor. My dad came from Trinidad to study and ended up in Dalhousie University medical school.

As Dalhousie was in the south end, that’s where we lived. I went to an almost all-white school where kids learned racism early and often. They referred to the north end’s main street, Gottigen Street, as “gotta get a gun” street. I also remember playing with kids in kindergarten or Grade 1 and having them sing, “Eenie meenie minie mo, catch a nigger by the toe …” (At least they got the words to the song right as it apparently started as a song about catching runaway slaves.)

We now have a unique moment in history to address anti-Black racism in Canada. People in power are suddenly eager to do things for Black folks. Black people should accept the offer and ask for everything they can get now, because these moments are fleeting.

Robin Browne is an African-Canadian communications professional and the co-lead of the 613-819 Black Hub, living in Ottawa. His blog is called The “True” North.

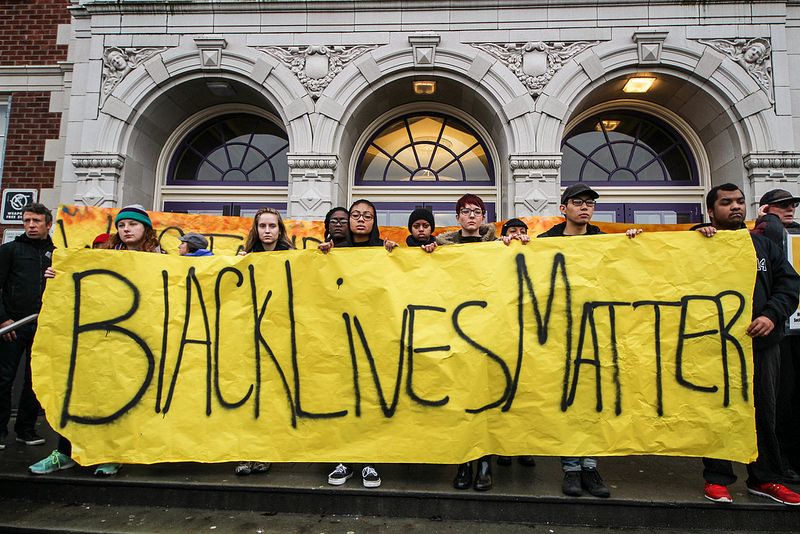

Image: michael_swan/Flickr