I remember being 14 years old and watching the media circus labeled “The Oka Crisis.” A fistfight in the bush between a brown man and a white man surrounded by white soldiers was played over and over for days on several different news stations. I identified with the brown guy and wanted him to win the fight.

It was primal instinct then to root for the person of colour who looked like me. As an adult who knows much more about the colonial history and practices of the stolen land called Canada that I live on, I now root for the Mohawk peoples as an informed ally.

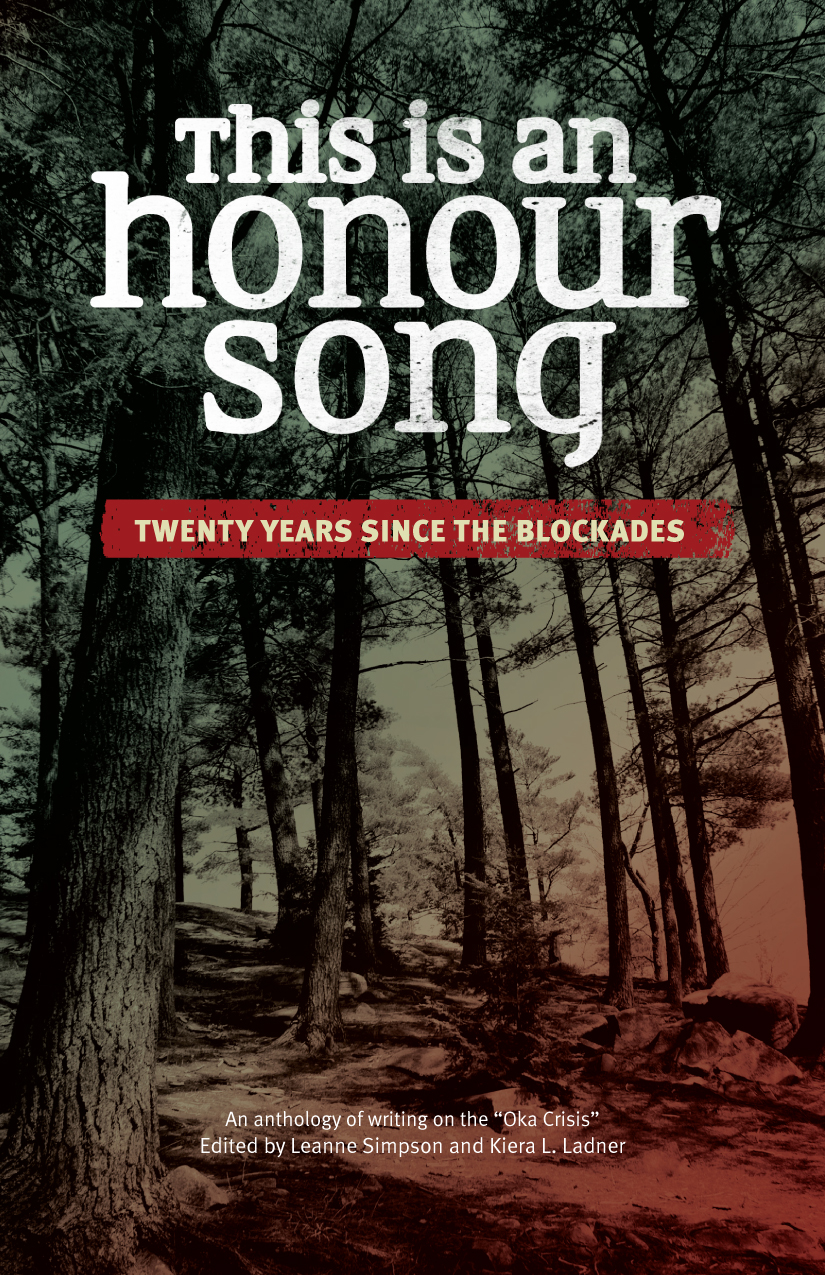

July 11, 2010 marks the 20th anniversary of what is now known as “Oka.” Leanne Simpson and Kiera Ladner, have compiled a timely and important anthology called This is an Honour Song: Twenty Years Since The Blockades.

Filled with soul grabbing poetry, academic and personal essays, beautiful artwork, a short story and a play, Simpson, Ladner, and their 33 co-writers — including well-known contributors such as Ellen Gabriel (who stood in the front lines at Oka), and respected writer and professor Patricia Montour — provide educational pieces about the events of the standoff. They also take a stance on paper by sharing new issues that have come since Oka, and how it influenced a new generation of activists who seek justice in similar battles in their own territories.

The strength of the book lies in its poetry and personal essays. Aboriginal feminist, activist and writer Lee Maracle writes that “poetry is song.” Poems and poetic essays sing truths about these writers’ experiences, reflections and hopes for a better future.

In her powerful essay “Rights and Roots: Addressing a New Wave of Colonialism,” Melina Loubacan-Massimo, a Lubicon Cree, writes about her traditional territory in northern Alberta. She shares past victories such as when the Lubicon Cree got much needed press during the 1988 Calgary Olympics about a standoff with Japanese logging company Daishowa. The standoff ended with Daishowa pulling out of a contract with the government of Alberta.

Massimo also writes of the current destruction of Lubicon land at the hands of oil companies. According to Loubacan-Massimo, the tar sands have “moved more earth than was moved for the Great Wall of China, the Suez Canal, the Great Pyramid of Cheops and the ten largest dams in the world combined. The targeted area of destruction will amount to the size of Florida or the country of England.” Her essay touches on environmental racism, the waste of water, the displacement of peoples, the massacre of wildlife, all of which is part of what she describes as “the biggest and most destructive industrial project in human history.” Although the descriptions of devastation are scary Massimo writes with optimism about a better future.

The number four is sacred in Aboriginal teachings. There are four directions, four grandfathers and four seasons. Clayton Thomas-Muller, took only four pages to send a message that could go round Mother Earth four times over. His essay “The Seventh Generation” recaps his learning about Oka on the news, how it changed his view of what it meant to be Cree, and what Oka means to all inhabitants of Turtle Island today.

“My human relatives, I write these words to encourage you to be strong and to continue to seek justice in our struggle. Do not give in to the quick fix of money and political favor of the state or from the corporations that control these colonial governments,” writes Thomas-Muller. His essay is raw and refined at the same time; his tone is both gentle and strong; his words are piercing and healing; his message is confrontational yet embracing. Thomas-Muller ends his teaching with a warning: “We will never stop, not for one second, so you better be ready.”

Like the Mohawk man I saw on TV at the age of 14, poets Ryan Red Corn and Al Hunter pull no punches. In his song “Bad Indians,” Corn starts with:

I was told by the old ones

that every song has a special time and a place where it’s sang

this is our song

and this is our time

It is Corn’s time, as it is the time of all the original peoples of this land, to stand up and end 500 years of colonial injustice. Corn writes the old, racist saying “the only good Indian is a dead Indian” and counters it by encouraging Aboriginal people to be bad if that’s what it means to be alive.

Hunter writes with the same fervour and intensity. To Hunter, hope is a noose placed around the necks of Aboriginal people. To hope is to wait, and Hunter calls his people to take action in his poem “Hope Can Be A Lie.” Twenty years after the blockade, after the event that had a nation and the world watching for almost two months, after the name “Oka” became forever etched in Canadian history, Hunter encourages peoples to speak up, free their voices:

Watch their world fall away

When you see that

You control

Your own

Destiny.

I control

My own

Destiny.

We control

Our own

Destiny.

We control

Our own

Destiny.